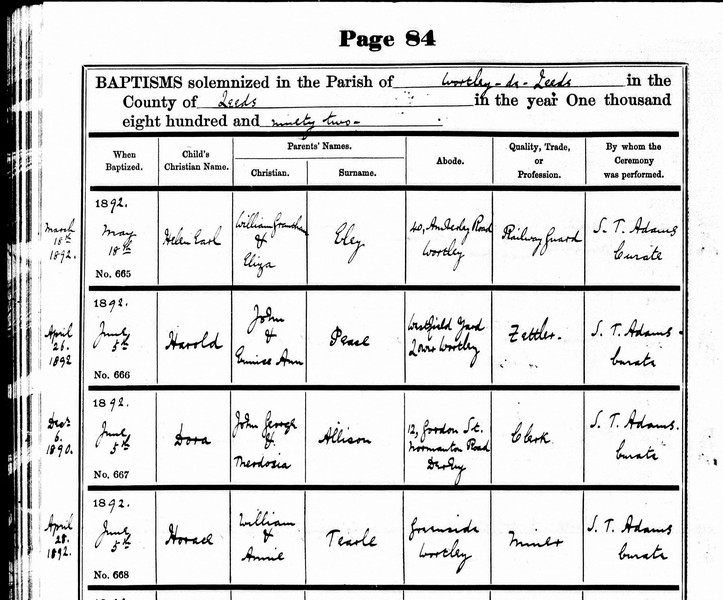

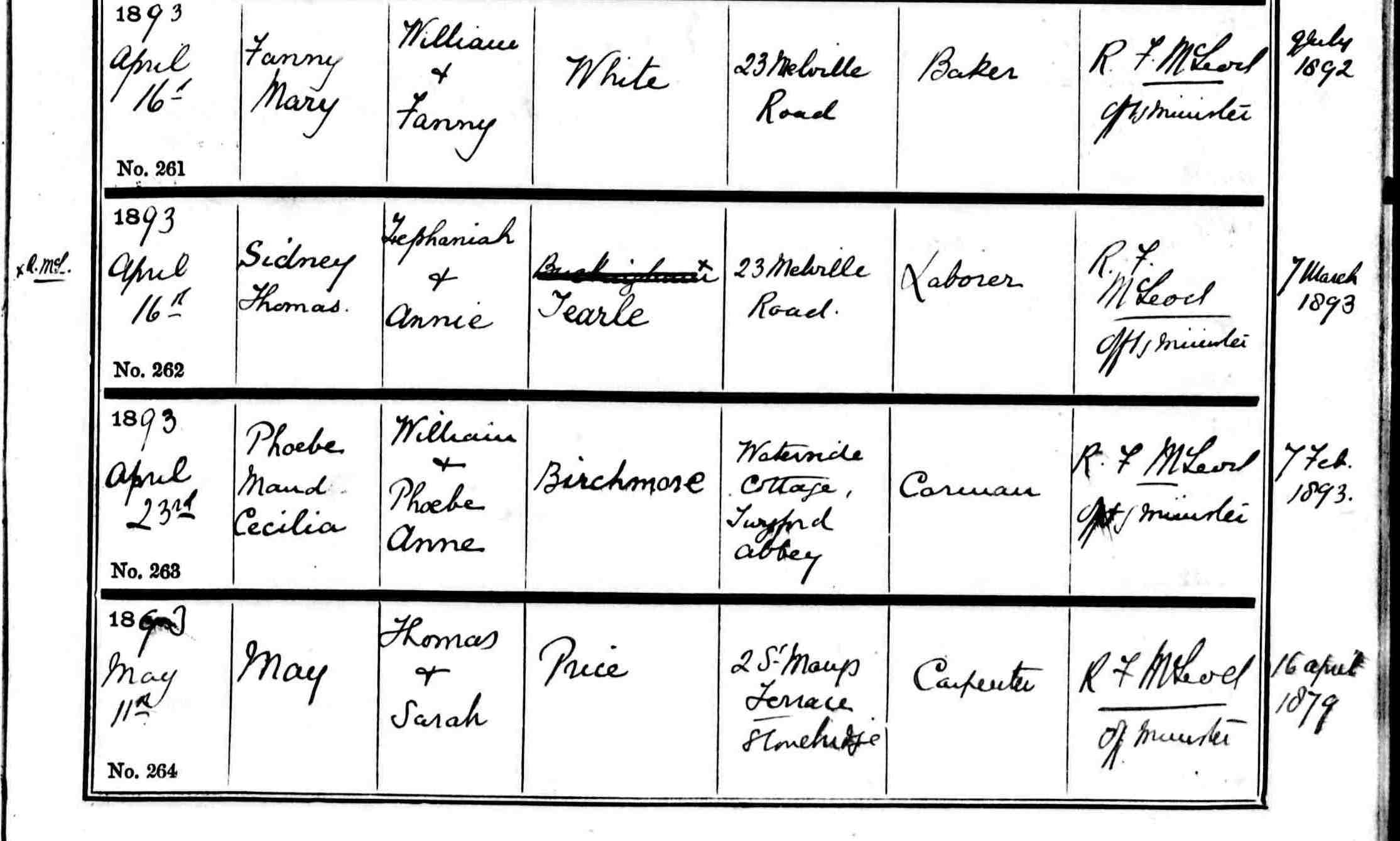

There really is a parish called Wortley-de-Leeds, and it was in St John the Evangelist Church of that parish, little Horace Tearle was baptised on 5 June 1892. The fear of babies dying drove Victorian parents to the the church as soon after their baby’s birth as possible. The church records show Horace was born on 28 April 1892. That is how anxious they were.

At the time of Horace’s Christening, William 1859 was a miner in Fromeside, Wortley, Leeds.

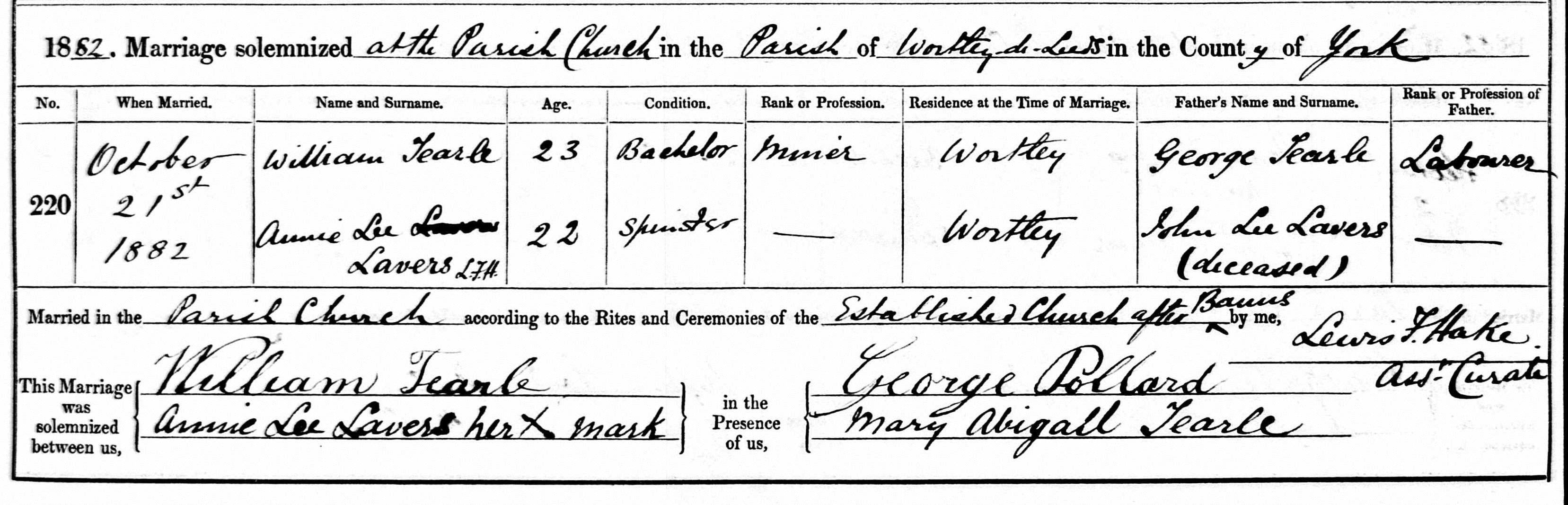

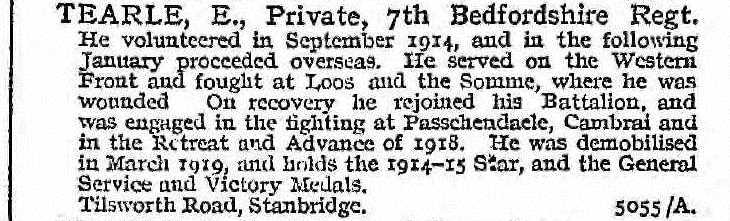

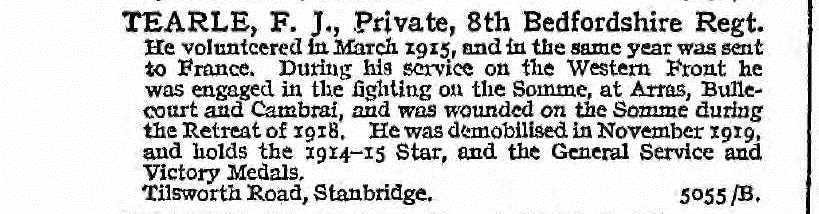

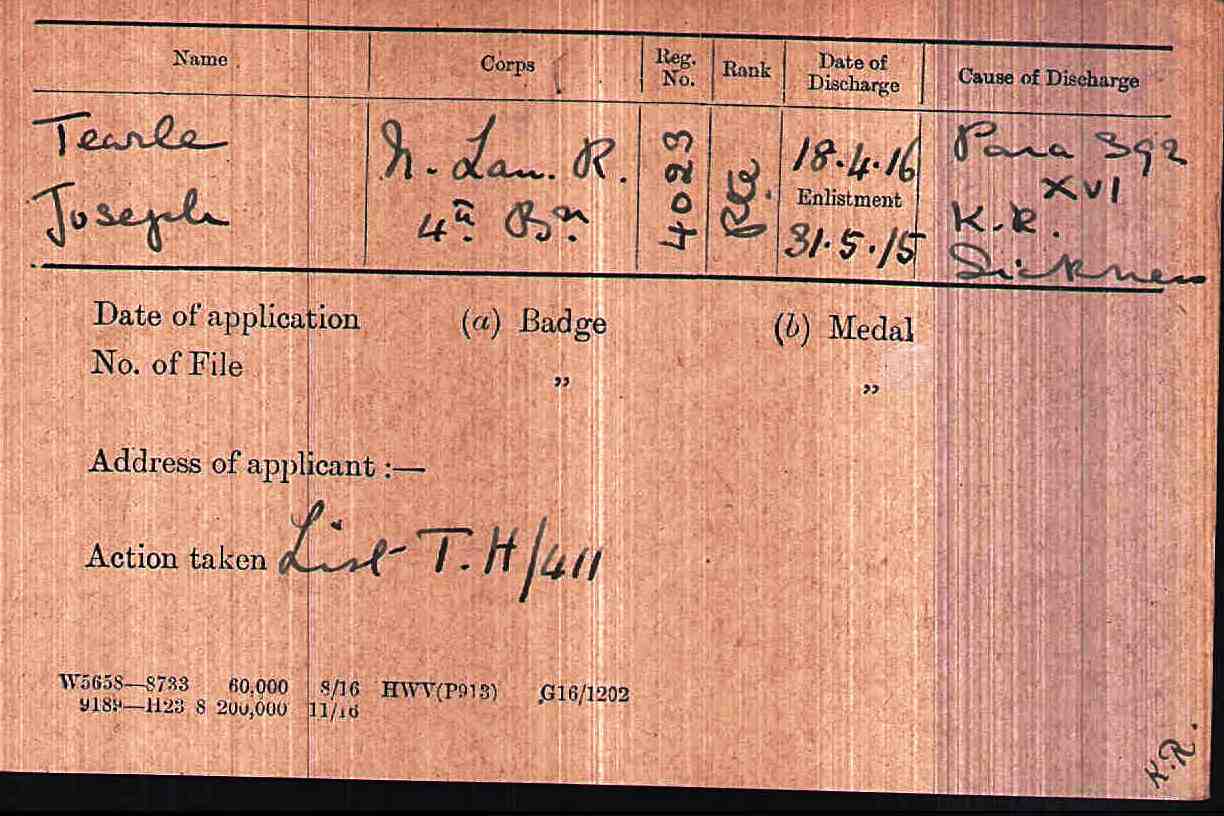

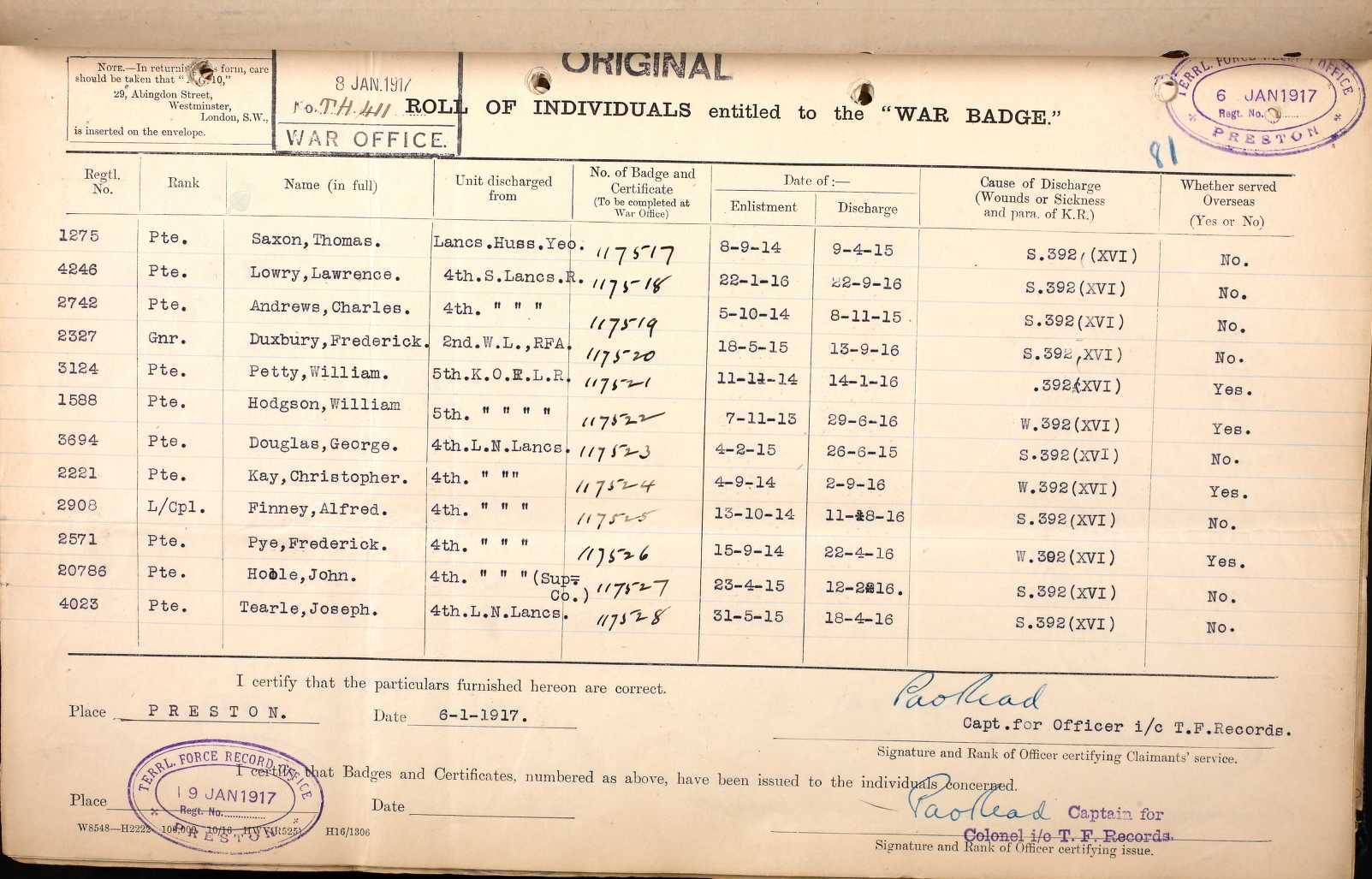

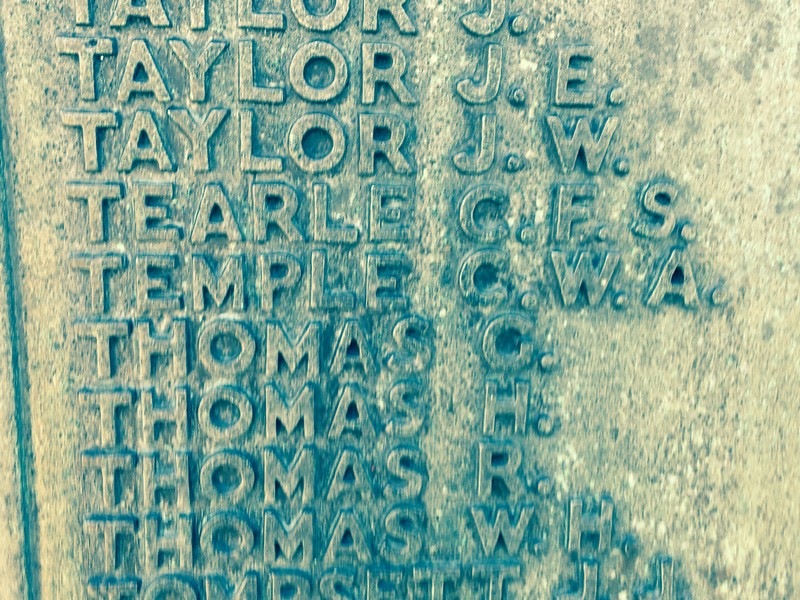

To put this family in context, William Tearle 1859 of Bramley, Leeds, married Annie Lee Lavers on 21 October 1882 in Wortley, Leeds. His parents were George Tearle 1825 of Leighton Buzzard and Maria nee Franklin. George and Maria’s first child, Julia, was born in Leighton Buzzard. Their next two children, James 1852 and Edward 1855 were born in Chipping Norton, Oxfordshire, and this James married Mary Abigail Ryder in Bramley, Leeds in 1875 and then emigrated to Australia in 1883. George and Maria moved to Leeds in about 1856, and the rest of their family – George 1857, William 1859, Elizabeth 1862 and Harry 1864 were all born in Leeds. George’s parents were Joseph Tearle 1803 and Mary Ann nee Smith. This is the family who moved from Leighton Buzzard to Preston and started the Preston Tearles. As you can see, George did not follow them to Preston, Lancashire; he went to Leeds, in Yorkshire. Charles 1894 of Preston and Horace 1892 are second cousins. The parents of Joseph Tearle 1803 were Richard Tearle 1778 of Stanbridge and Mary nee Pestel, and Richard’s parents were Joseph 1737 and Phoebe nee Capp. Thus, Horace is on the branch of Joseph 1737.

In the 1800s we were living in the grip of the Industrial Revolution, where some families made vast fortunes, whilst their factories blew contamination into the air, poured pollution and poison into the rivers, and allowed their workers’ conditions to be little better than slaves. No wonder their babies died. It was also a time of upheaval and mass migration. As mechanisation modernised farming, and fewer labourers were needed, so the farming life became untenable when people could no longer make a living from the land.

George and Maria moved North. William became a miner; here is his marriage:

It is a poignant reminder of the life they left behind; far from rural Bedfordshire, William was a miner, and George, who had been an Agricultural Labourer, was now a “labourer in a brick works.” Annie, the local lass, cannot write, but William signs in a beautiful copperplate hand and one of the witnesses is his brother James’ wife, Mary Abigail nee Ryder. Within a year, they would be in Australia.

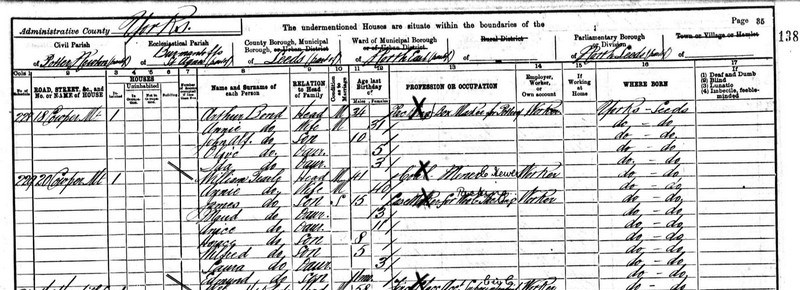

The 1901 census, above, notes that William is a coal miner, and son James is working in a wool factory. You will have noticed that William and Annie’s first child was called James, no doubt after William’s favoured elder brother. Horace is eight years old.

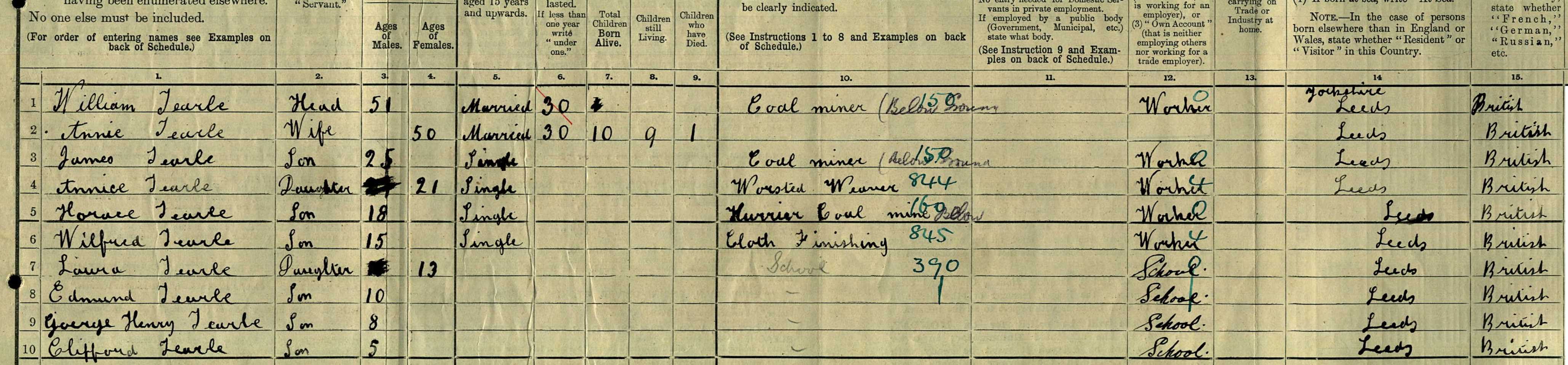

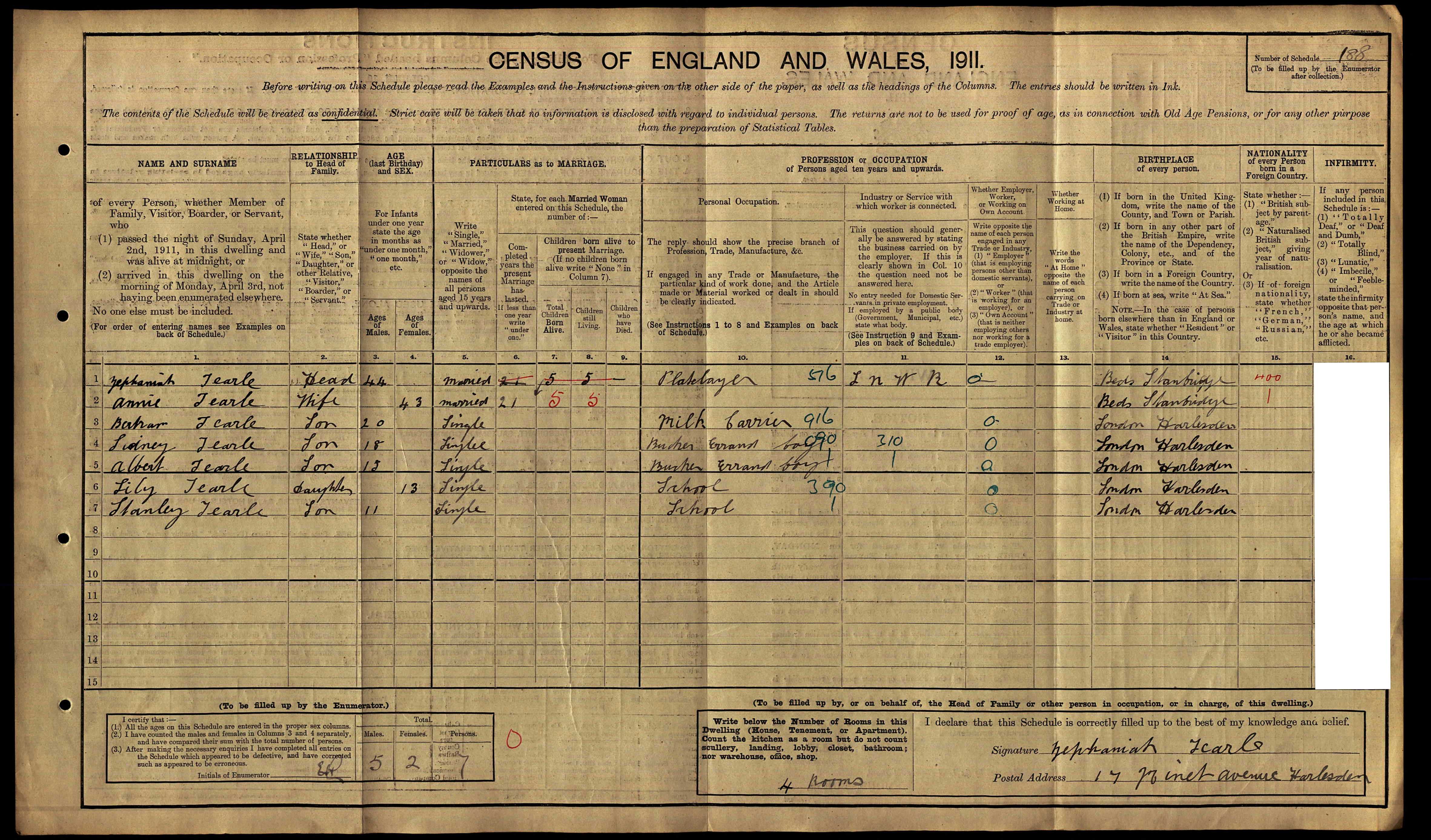

The 1911 census tells us (as usual) quite a lot more. But amongst all the data, William, James and Horace are “Below ground” miners. Unfortunately, William and James do not tell us their exact roles in the mine, but Horace does. He is a “hurrier.” His role was to pull heavy carts of coal along the underground pathways to exits where the cart would be winched to the surface. The hurrier was tied to the cart with a heavy chain, and usually, at the other end of the cart, there would be a girl who was the “thruster,” pushing the cart with her hands and forehead, usually while kneeling. She would lose her hair over time due to the pressure of the cart on her head. Fortunately, Annice and Wilfred are in cloth-making factories, rather than the dreadful life girls had underground. Still, working in a factory was a job of long hours, low pay and awful working conditions. It is nice to see that all the younger children are at school, because in the 1840s children as young as five years old were working underground, in mines. Also in this picture of 1911 is Horace’s immediately younger brother Wilfred Tearle 1896 of Bramley, Leeds. He would share Horace’s story.

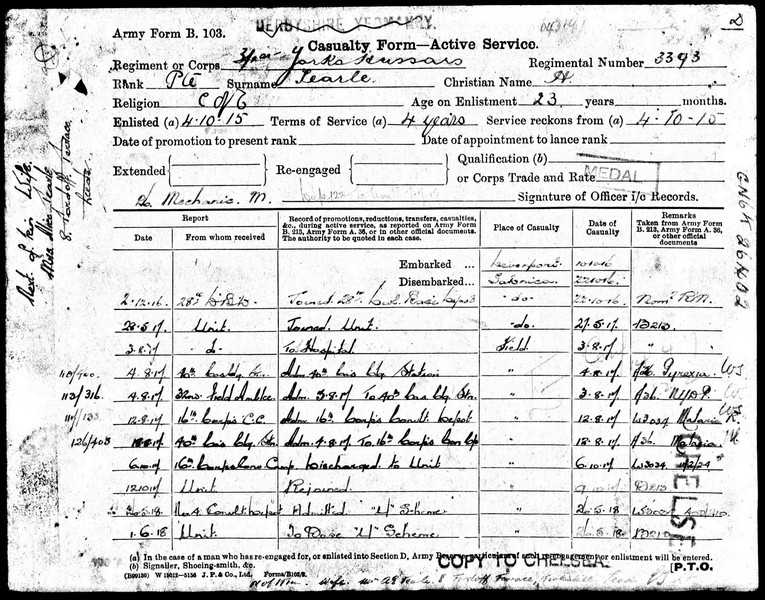

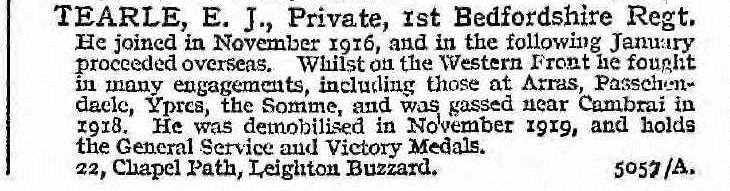

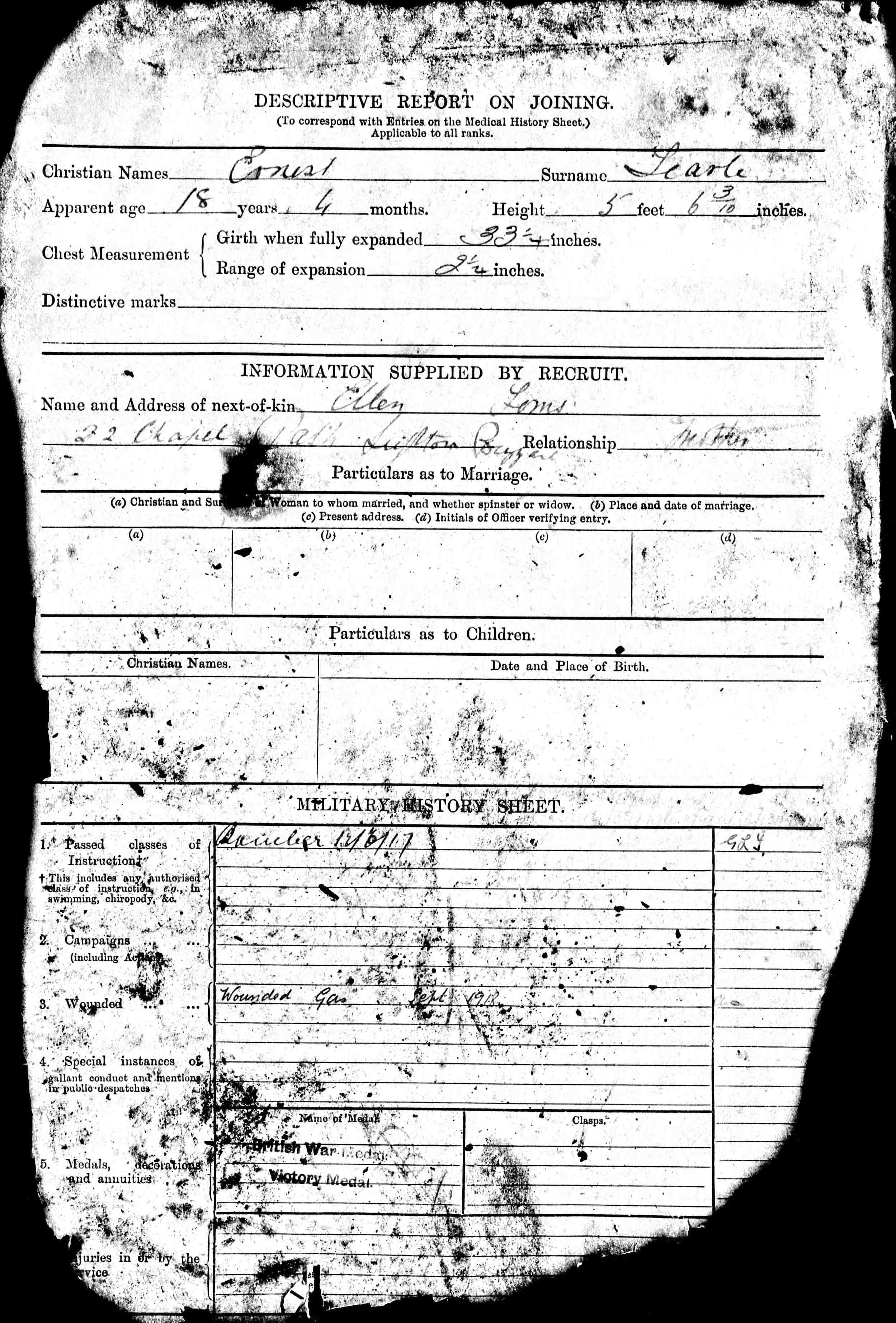

Goodness knows what drew Horace into The Great War, perhaps getting out from under ground to help in the developing adventure in Europe might have been a pull, or he was volunteering before he was conscripted? For whatever reason, Horace signed up on 4 Oct 1915 (the day he attested for “4 years service in the United Kingdom”) a full five months before conscription was enforced in March 1916. He was given the number 3398 and was inducted into the 3/1 Yorkshire Hussars. He was 23 years old, 5ft 6in tall, he had good vision and good physical development. He was kept on “Home” duties, meaning anywhere in the UK including Ireland, and during that time he married Annie Elizabeth Peat, on 3 June 1916. Married life came to an abrupt halt on 10 Nov 1916 when he boarded a ship in Liverpool, bound for Greece, which arrived in Salonica on the 21st. He was in the MEF, the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force. Fortunately he was a few months too late to join the action in Gallipoli, but he would have been told that his role was in warfare over Greece, the Balkans and Turkey.

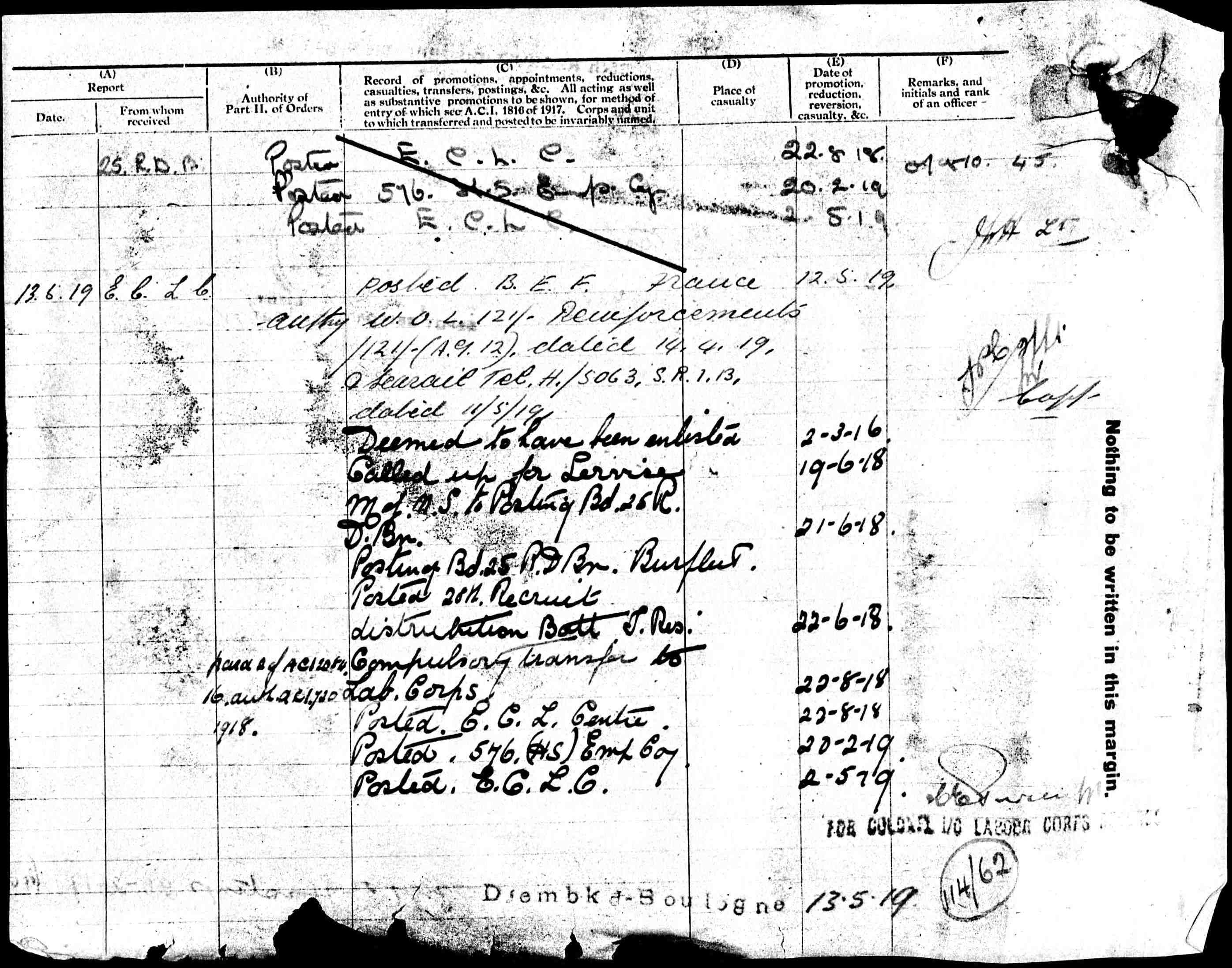

I have one document that tells a great deal about how the war treated Horace. Here it is:

Firstly, you can see that he has learned another skill; he is a mechanic. In a later document he is referred to as an engineer. Perhaps when he gets back home, he may not have to be a miner. On 3 Aug 1917, Horace was driven to a field hospital with an unknown condition. On the 4th, he had an extremely high temperature, and on the 12th he was diagnosed with malaria. His life had now changed forever; you do not recover from malaria, you simply get used to coping with it. In November he is returned to his unit. On the page after this one, there is a stern order stamped on his card:

“Malaria case – Not Available for a Theatre of War where MALARIA is Prevalent.”

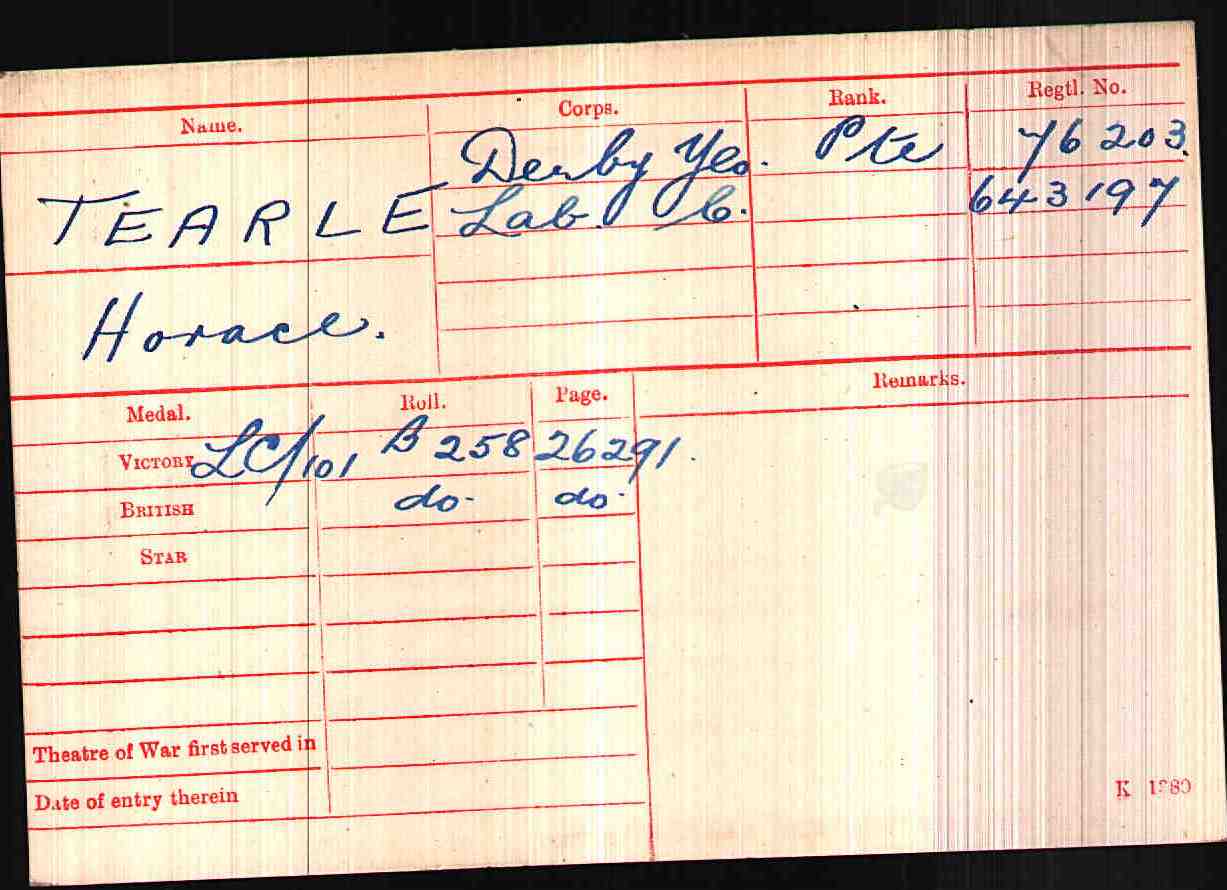

The fact that the order is stamped on his record shows us that this was a common event. He was posted to other units – the Royal Dragoons and the Derby Yeomanry, but he was moved on – somehow he did not fit their needs. He was finally transferred to the Labour Corps. When he was well he could work, and when he was having a malaria “turn” he could rest. On 2 Nov 1918, he joined “A” Company, the Labour Corps. He would be used to move goods and clean up after the war. Armistice day arrived on 11 November 1918, and Horace’s service was reviewed. He had enlisted on 4 Nov 1915, been in the MEF from 10 Nov 1916 to 10 Jun 1918 and then on “Home” duties until 7 Nov 1918, a total of 3 years and 35 days. During that time, Horace was transferred to Aldershot Barracks, in Hampshire. In August 1918, with too much time on his hands, Horace got into a drunken state and overstayed his leave by almost half a day. He was loudly admonished, and given three days confined to barracks as a punishment, and probably sent on parade-ground cleaning duties. It was the only blemish on his military record.

On 7 Nov 1918, Horace was transferred to soldier class “P”. He was now the reserves, he could go home, but he might also be called up at any time until his four years was up. To all intents and purposes, he was free.

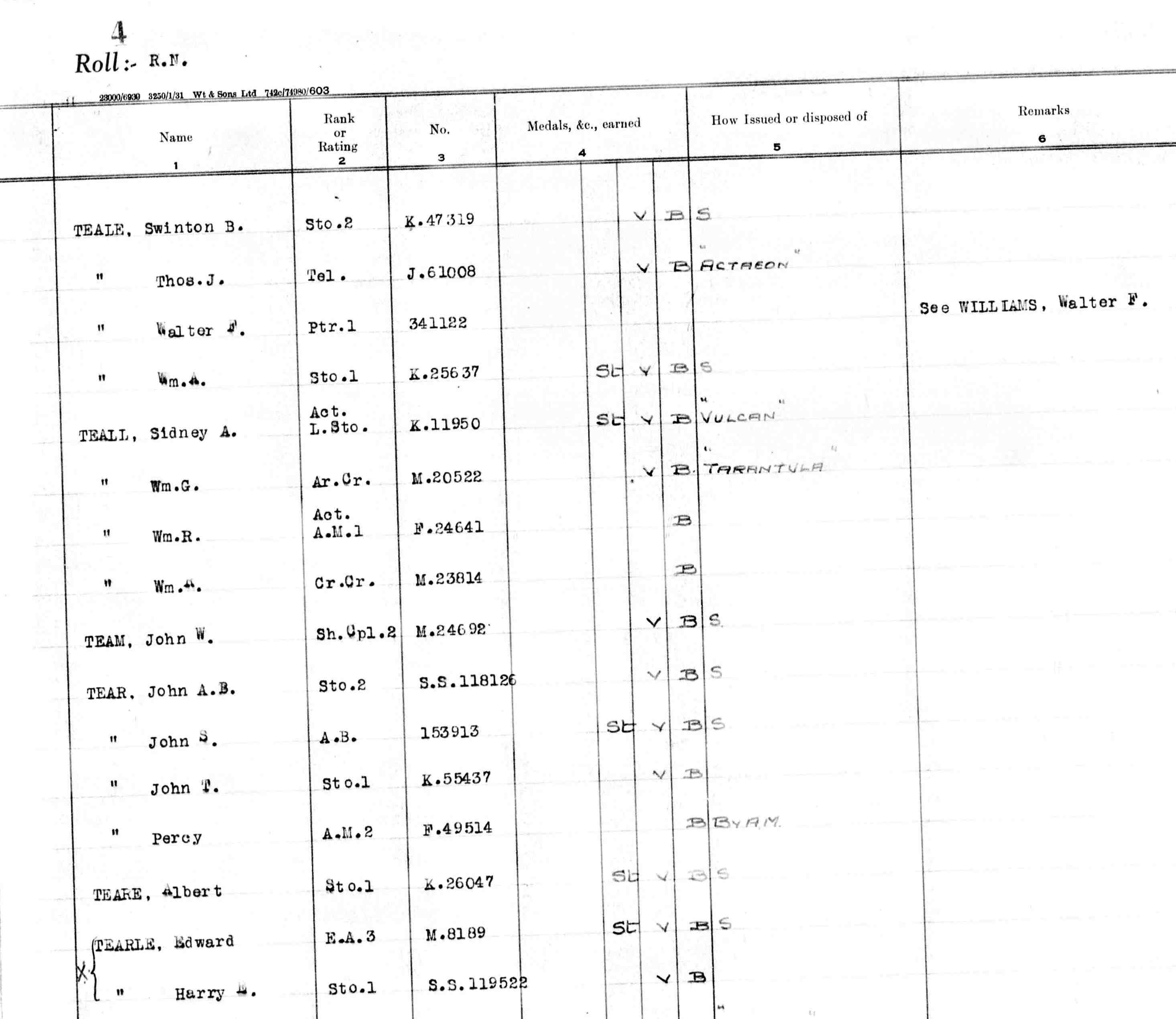

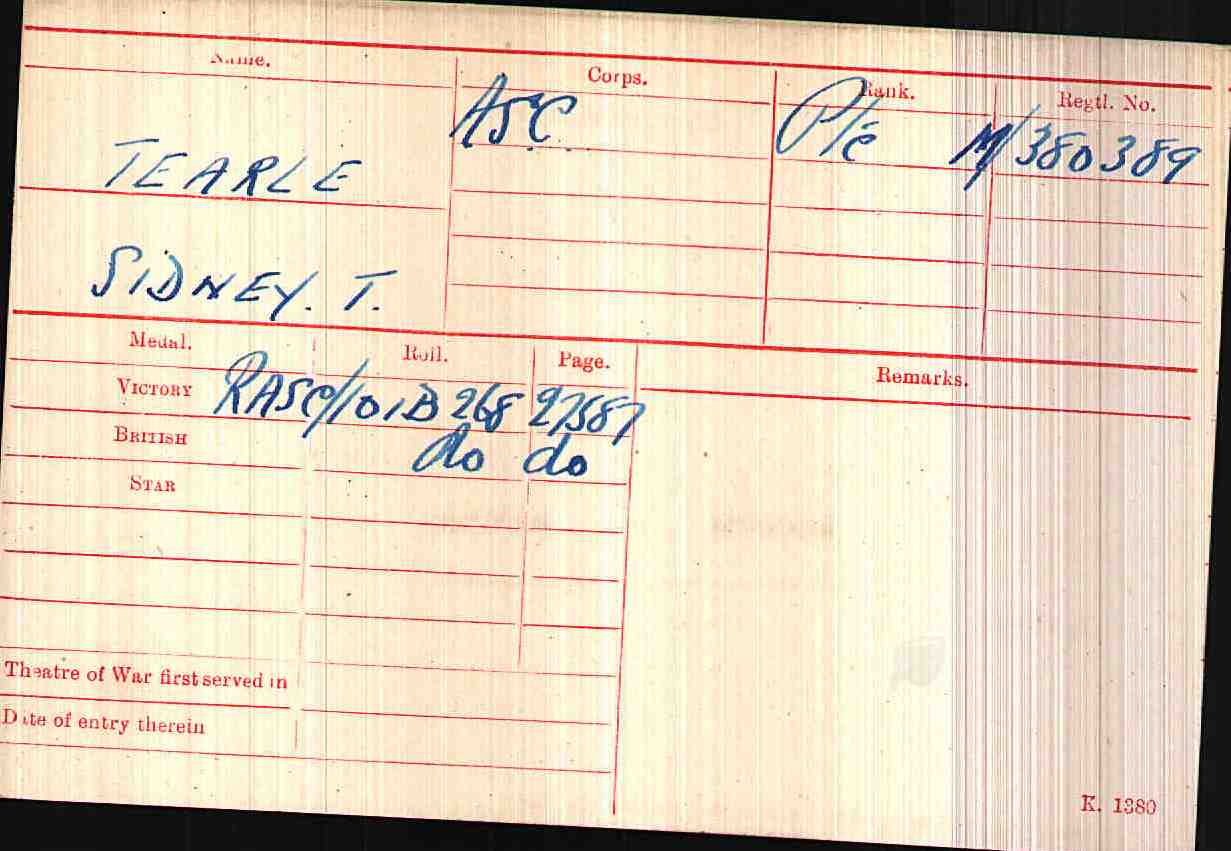

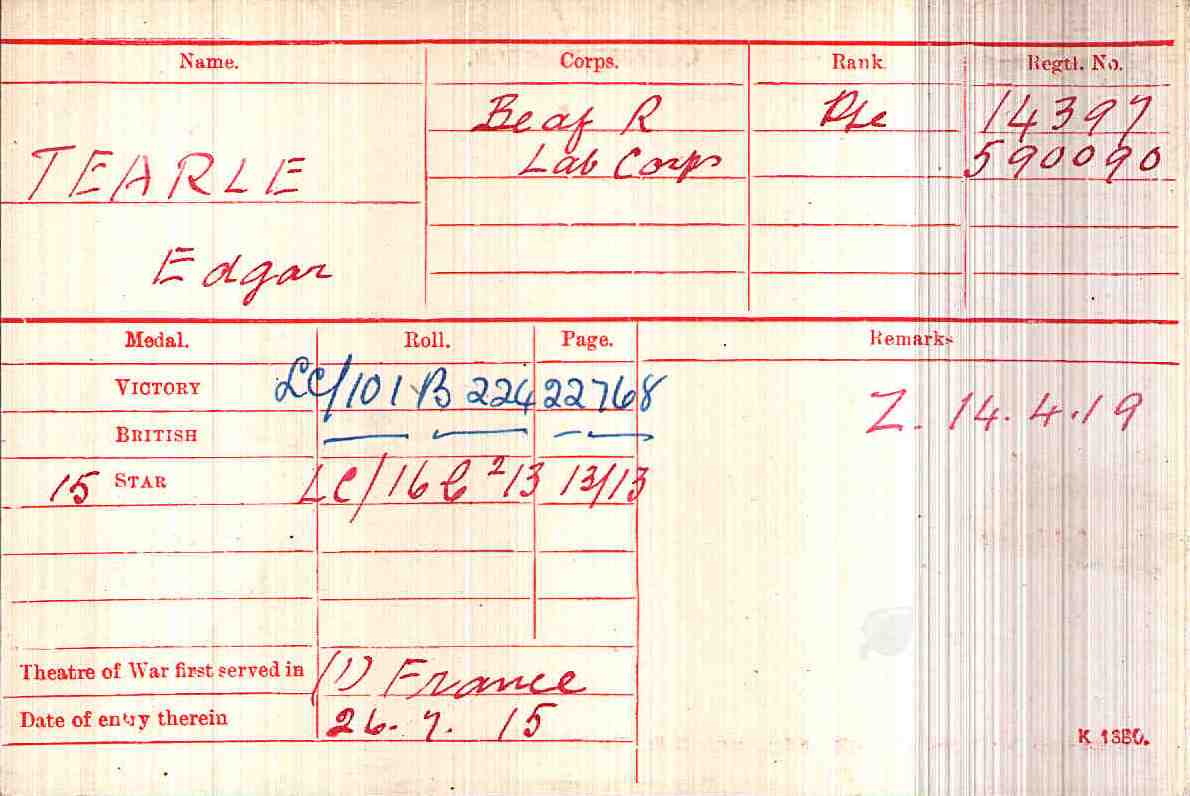

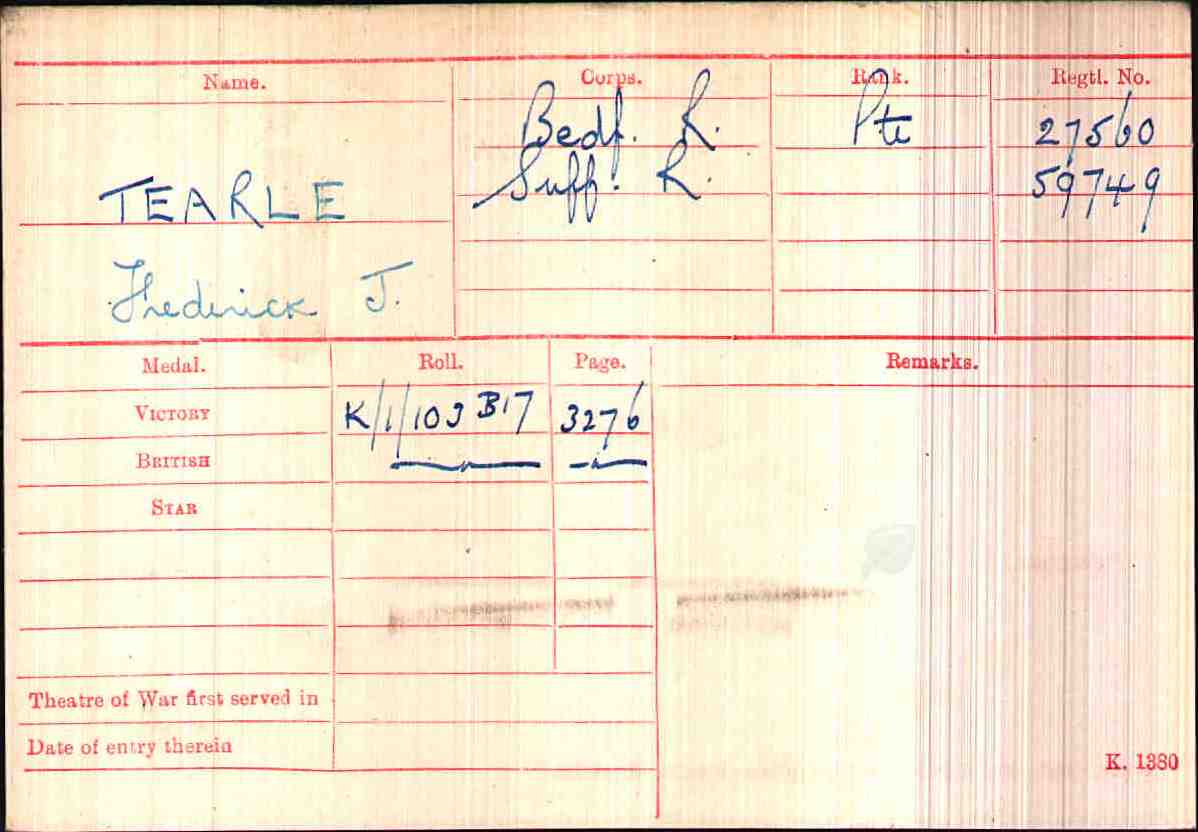

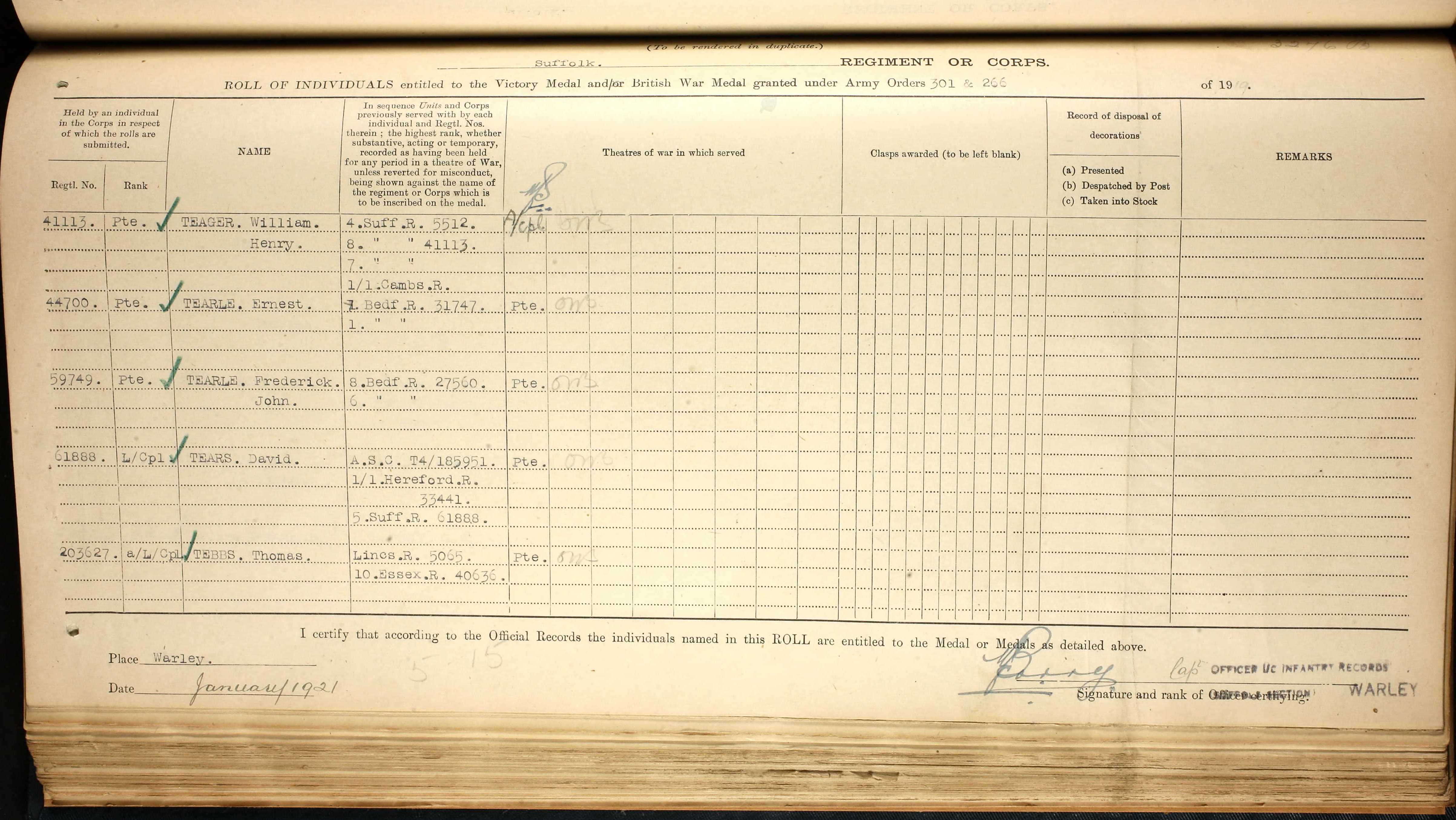

Here is his medal card, which shows that the Labour Corps (his last unit) had gathered sufficient information to award him two service medals – the Victory Medal and the British Medal. In 1922, Horace signed for the receipt of his medals. With his malaria always threatening, and boiling over at times, it must have been difficult for him to accept that this is all he got for the pain he would endure for the rest of his life.

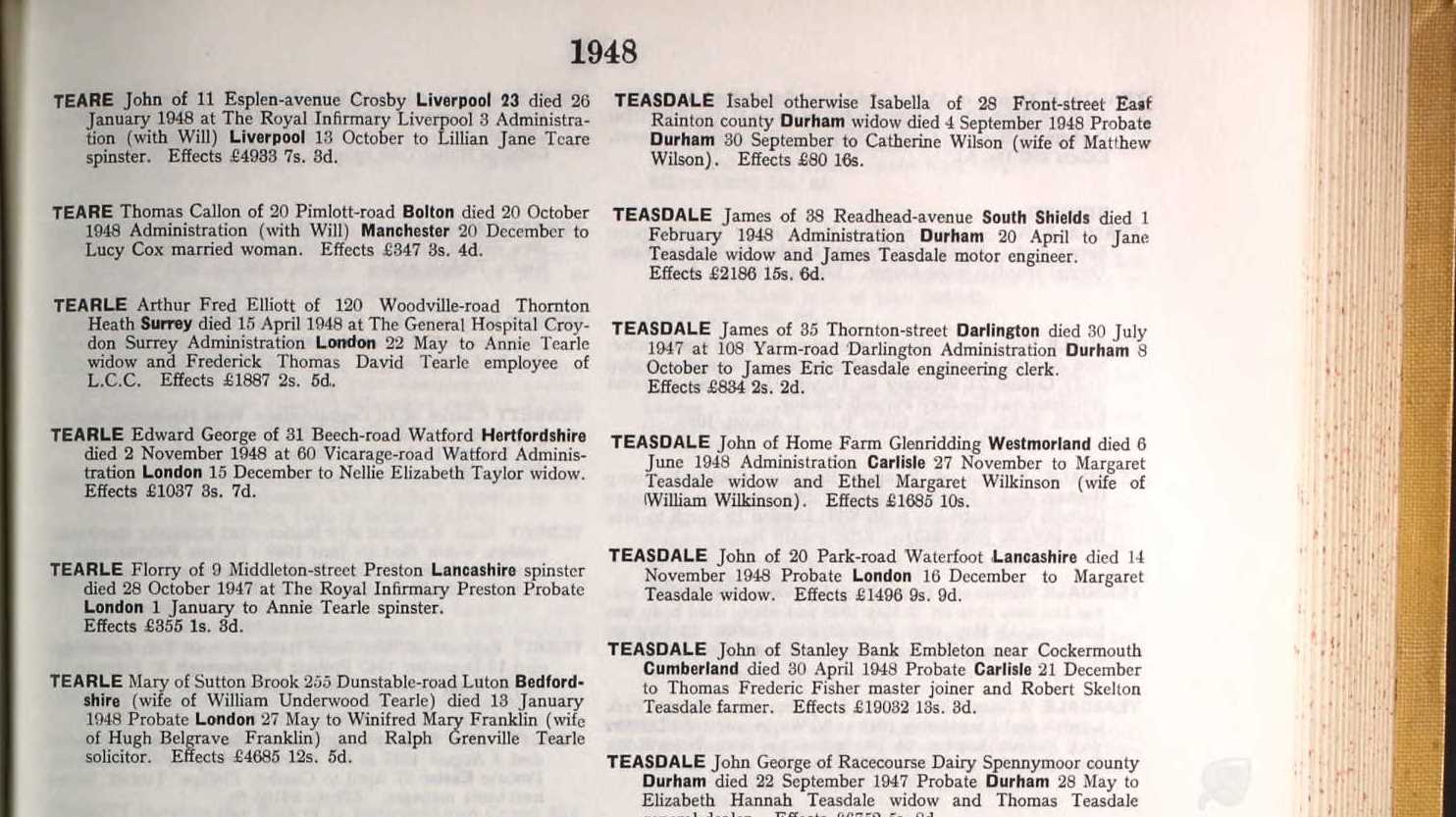

I know very little about what happened next, except that he and Annie had a girl, Joan, in 1920, and that Horace died in 1929, just 36 years old. Malaria still kills millions of people each year, and Horace’s fight with it in the 1920’s would have been difficult, and often very painful and debilitating. It is a very sad end for a man who had hoped for so much more.