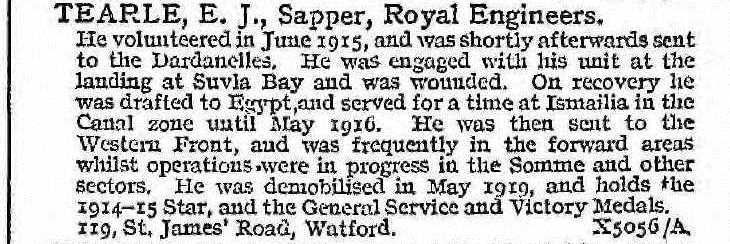

Let’s start with Edward’s entry in “National Roll of the Great War” because although the paragraph below was written at the end of his service, it will help us introduce him – not least because he is now on my list of men who fought in Gallipoli. And so far, none have come out unscathed.

Tearle, E J (Rgt No: 101941)

You can see from “National Roll” that Edward’s WW1 experience was definitely in two halves. He was wounded in Gallipoli, recovered, went to Egypt, and then he was sent to Europe where he was kept out of the firing line, but was still working. There is one document that spells this out:

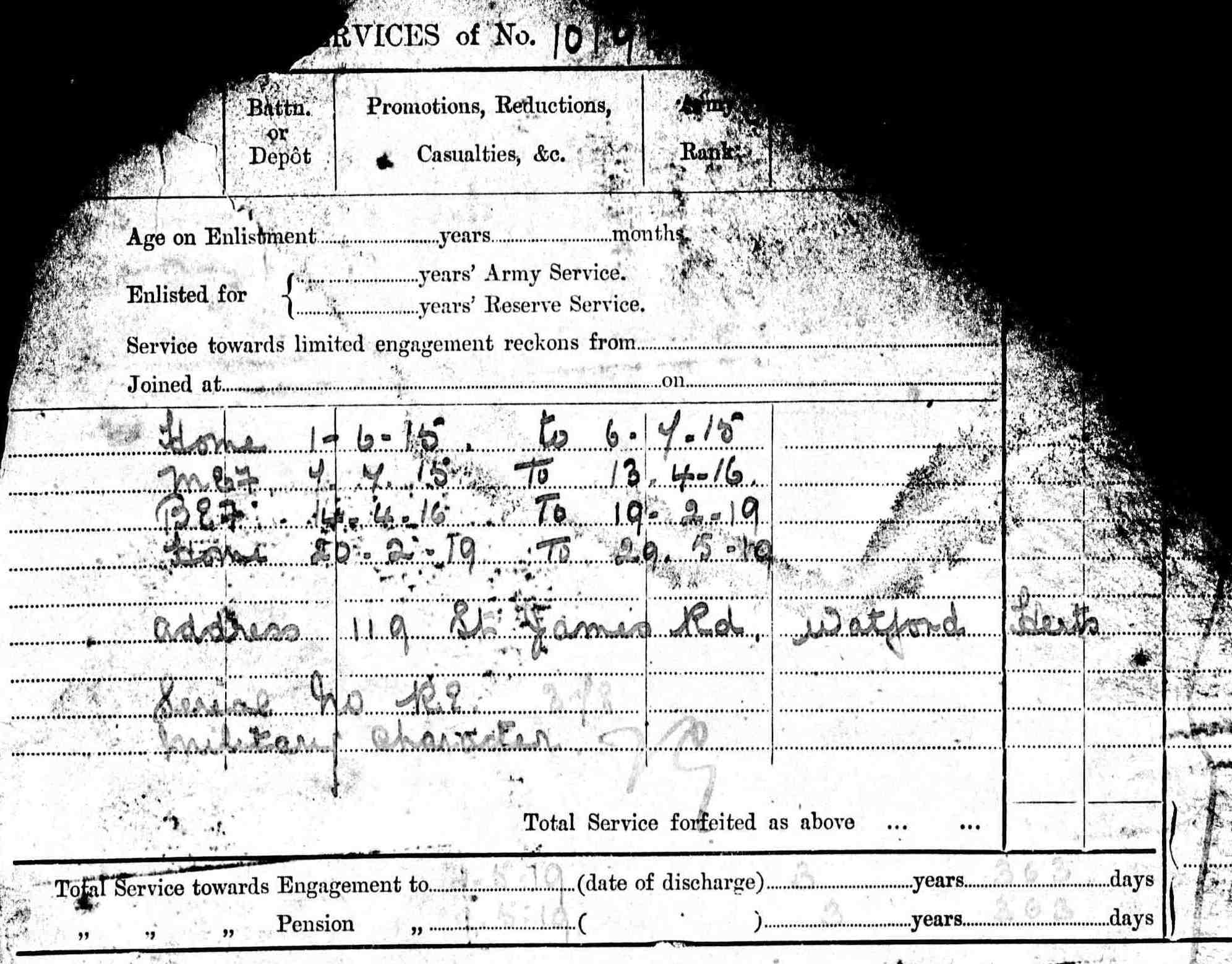

This is the document from Chelsea that tells us most about Edward’s career. You can see that he joins the Royal Engineers on 1 June 1915, but in only a month’s time, he is in the MEF, the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force, and off to war somewhere in the Middle East – or so. One month’s training? I found the reason – Edward had already been involved with the 2nd Volunteer Battalion, Hertfordshire Regiment. It is commendable that he joins the war effort so soon after war is declared but another thing you may have calculated by the title of this story, was that he was 40yrs old at the time. He said he was a stone mason, so he was signed up for the Royal Engineers.

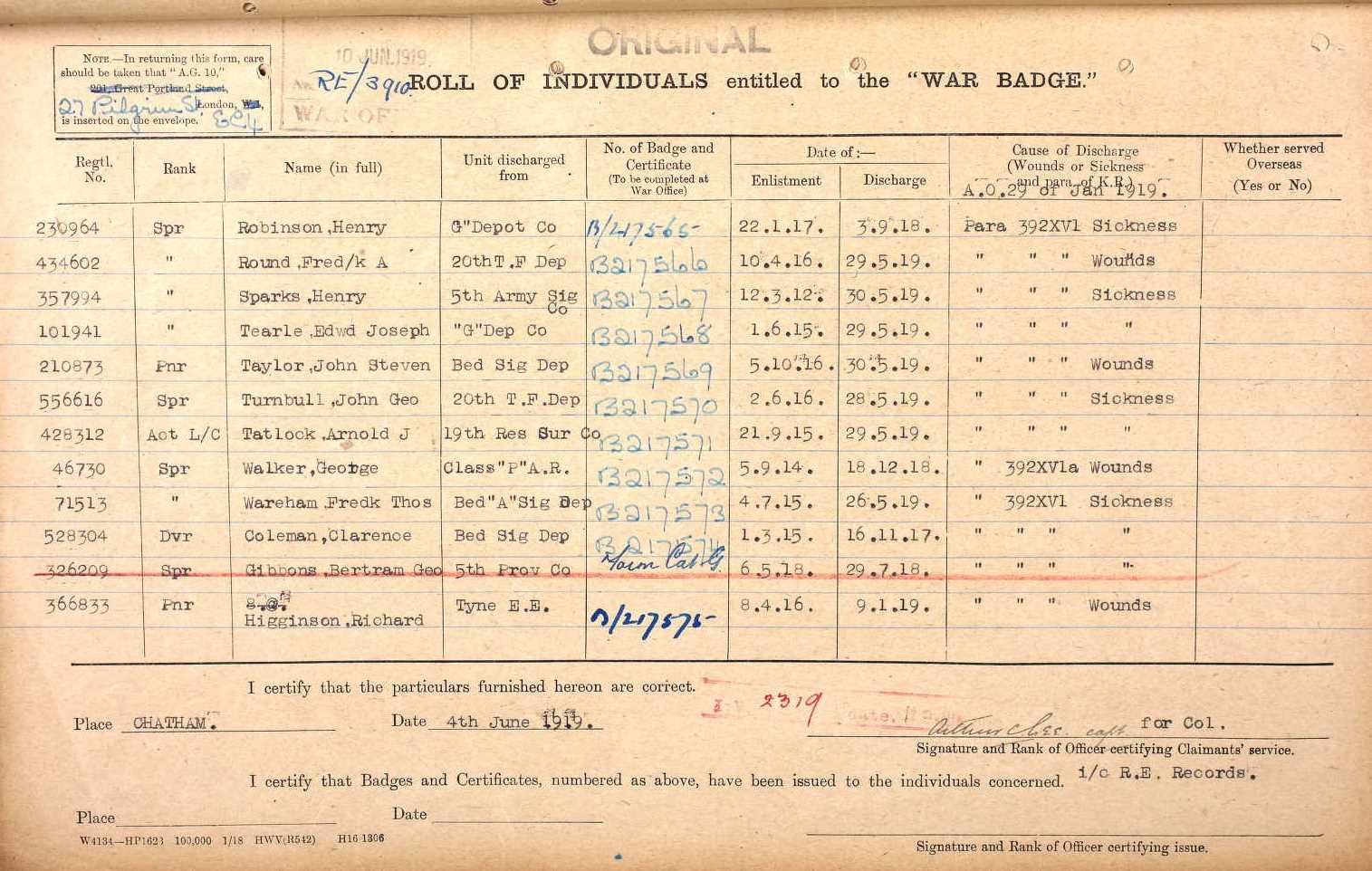

After a short but memorable stint in the MEF, Edward was sent to Europe with the BEF (the British Expeditionary Force) and it would appear he was kept well out of trouble, but obviously still able to work. He accumulated a total of 3yrs 363 days of overseas service and left Europe in early 1919, to spend a few months being assessed, and then being discharged on a Para 392 “Not fit enough to be a soldier”. As you can see from the document below, it was due to sickness.

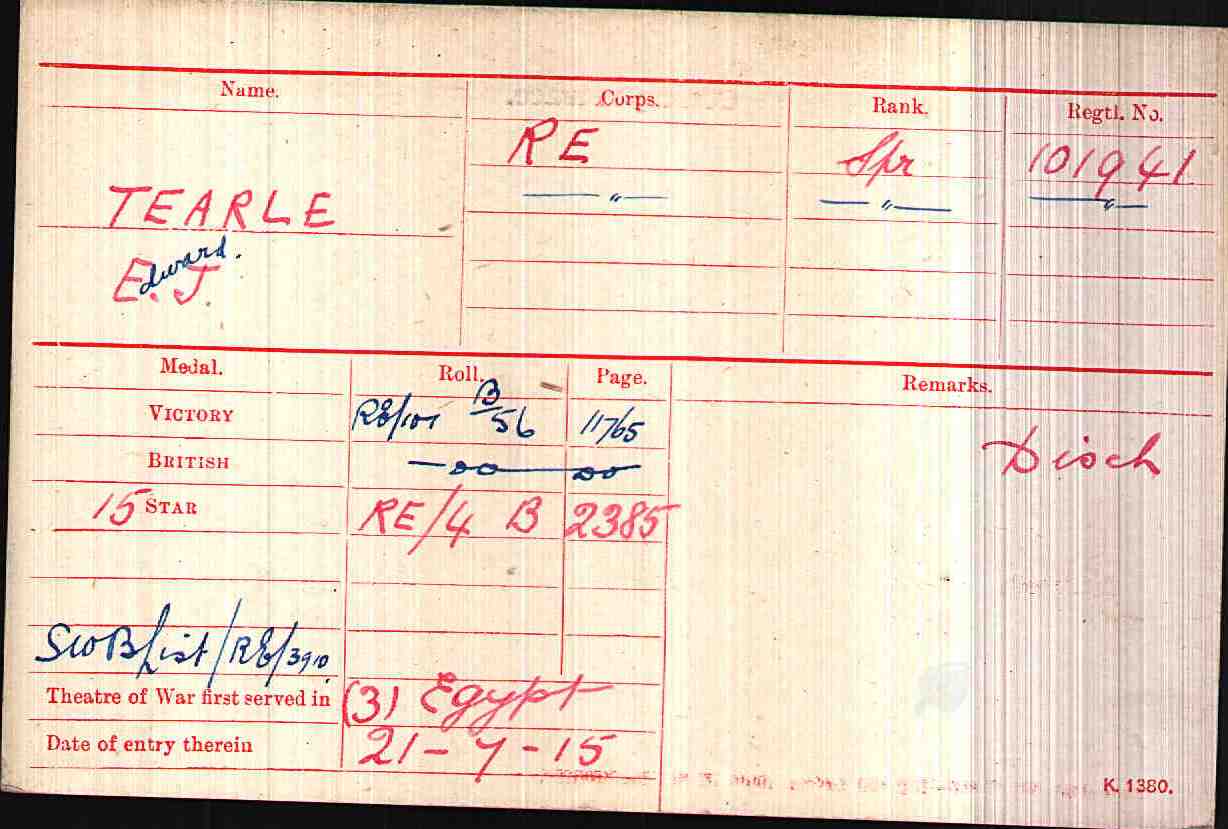

We can speculate all we like in the absence of documented evidence, but there is a range of very nasty diseases you can get from fighting in Gallipoli or Egypt; and Edward could have caught his, as Arthur Walter Tearle did, from hospital. Without the documents above, we would never have found out about Edward’s Silver War Badge, because below that is the card that recorded his service medals.

He did not get the 14/15 Star because he was not overseas in 1914, but you can see he has been awarded the 1915 Star, the British and the Victory medals. I assume the date of 21 July 1915 (and not 1 July 1915, which was his MEF starting date) being recorded as his entry into the Egypt Theatre of War, is the date his ship anchored at Suvla Bay, in preparation for the landing in Gallipoli on 6 August.

Edward left the army and went back to civilian life on 29 June 1919. Twenty years earlier, he had married a Hemel Hempstead girl (who lived barely 10 miles away) by the name of Jane Picton, in 1897, and his eldest son, Edward George, was born in 1898. In 1914, he was 16yrs old. On 22 June 1918, at a little over 20yrs old, he joined the Labour Corps and went to war, too. His war was short, of course, but he did go to France.

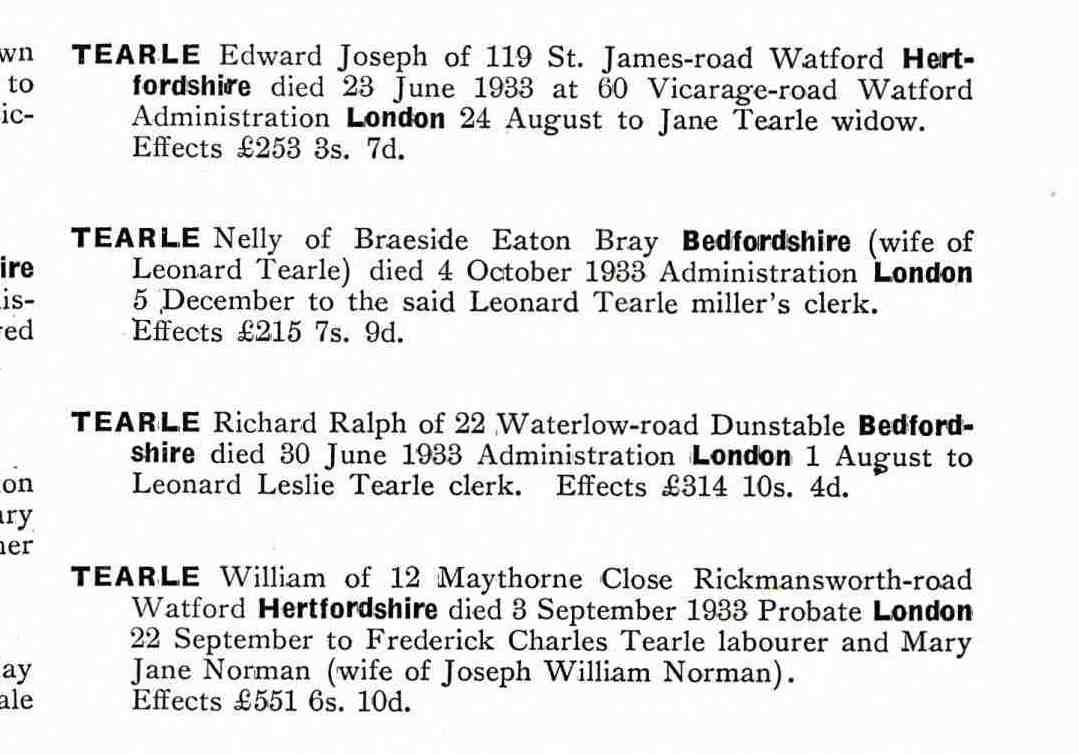

Edward’s sickness never left him. He died on 23 June 1933, at 60 Vicarage Rd, Watford, only 59yrs old. His entry in the London probate register is pretty grim, and probably reflects the debilitating condition that the war had given him.

When Elaine and I visited the Vicarage Road Cemetery in Watford, we found a corner that had so many Tearle graves and headstones, we called it Tearle Corner. Edward’s second son, George, was there, as were both he and Jane. The grave reference is K-953.

Tearle Corner headstone K-953. George 1902-1931, Edward Joseph Tearle 1874-1933 and Jane nee Picton. Vicarage Rd Cemetery, Watford.

The ancestry information on Edward that you need to know is as follows: his parents were Jabez Tearle 1844 and Susannah nee Payne, his grandparents were George 1818 and Annie nee Haws, the grandparents of many Watford (and Australian) families today, and George was the son of Abel 1797 and Hannah nee Frost. Abel, of course, was the son of Fanny Tearle (who became Fanny Johnson) who was a daughter of Thomas 1737 and Susannah nee Attwell.