A little family history.

“Belfast?” Elaine’s always up for going anywhere new, but this was unusual. “Is it safe?”

“EasyJet goes from Luton and we haven’t been there yet.” I looked up the short report from Jeanette Youngman. “We may be able to go to Lisburn once we get there and look up a few headstones in Magheragall.”

“Oh, nice. And?”

“And after that we can do as you like.”

Perhaps as early as 1980 Jeanette sent me a report she had commissioned from a family research company in Belfast. She wanted to know the story of her grandfather, William Dawson 1857-1910. She had been to Belfast and visited a Ewart family there and they had been very hospitable. The names on the report were echoes of the names that Mum’s family had used in NZ.

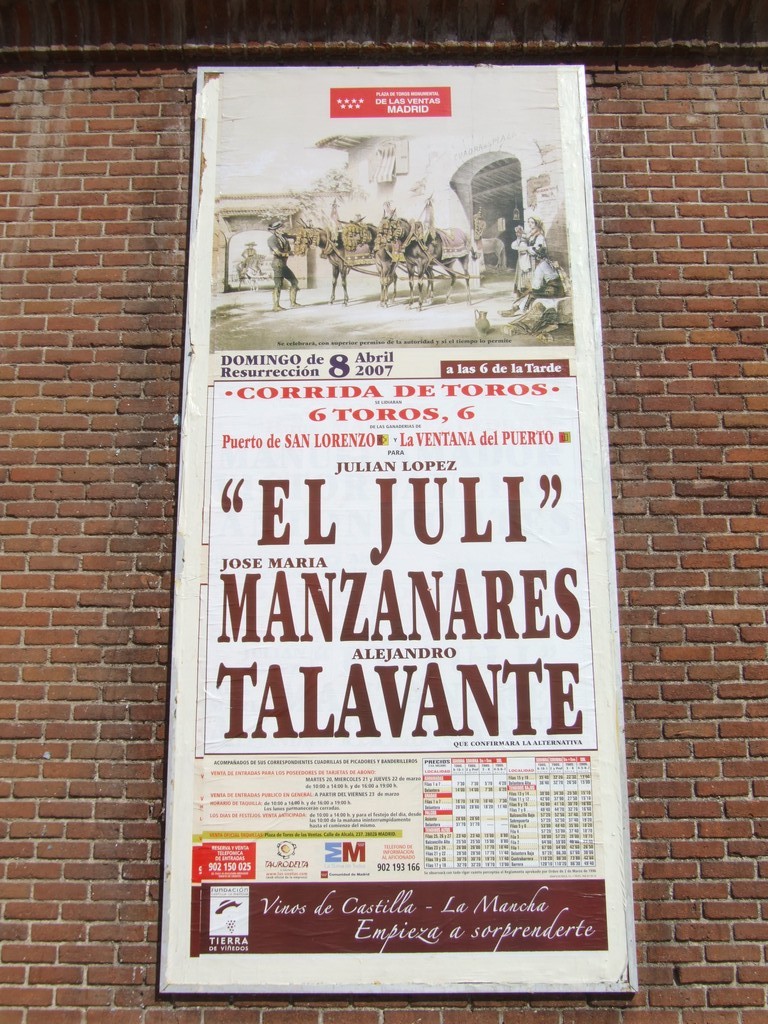

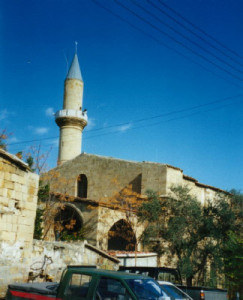

Briefly, James Dawson of Lisburn 1776-1829, had a son William Dawson 1821-1889. This William married Ann Ewart (1826-1898) in Magheragall Parish Church (above) in 1852. Her parents were John Ewart and Jane Kirk. They had married in the Magheragall Church in 1809. William and Ann had 9 children one of whom was Richard Dawson 1855-1925, his immediately younger brother William Dawson 1857-1910 and his immediately younger brother James Ewart Dawson 1860-, and finally Thompson Dawson, about 1863, all of them born in Magheragall parish. William Dawson 1857-1910 was my maternal great-grandfather, as well as being Jeanette’s grandfather. So Jeanette (nee Dawson) was the same generation as my mother. By going on this visit to Belfast, I had an opportunity to seek out just a little of the story of William and his family.

My great grandfather, William Dawson, emigrated to New Zealand, where he met and married a Northern Ireland girl, from Lisnacloon, which is as far west as one can go, called Marguerite Matthews, after whom my mother was named. One of their sons was my grandfather, James Ewart Dawson and my mum named me after him. She called me Ewart, she said, because she didn’t want me called Jim. Mum always told me that William had left from Lisburn, which was close to Belfast.

We walked straight through Belfast International Airport, no passports asked for, and caught the 200 bus to the Central Bus Station. We had to take our bags to the Welcome Centre because our hotel wouldn’t store them. Something to do with security. Why the Welcome Centre would store them and not the hotel escaped me.

“The weather report said that it would rain all weekend, so a nice sunny morning like this might be the best chance to photograph a church,” I said to Elaine.

You pick up the bus for Lisburn from the Central Bus Station. No 51. As the bus left the station, on our right hand side was a huge notice painted on the end of a terrace house:

“You are entering Loyalist territory…” I missed the rest.

Are they still doing that?

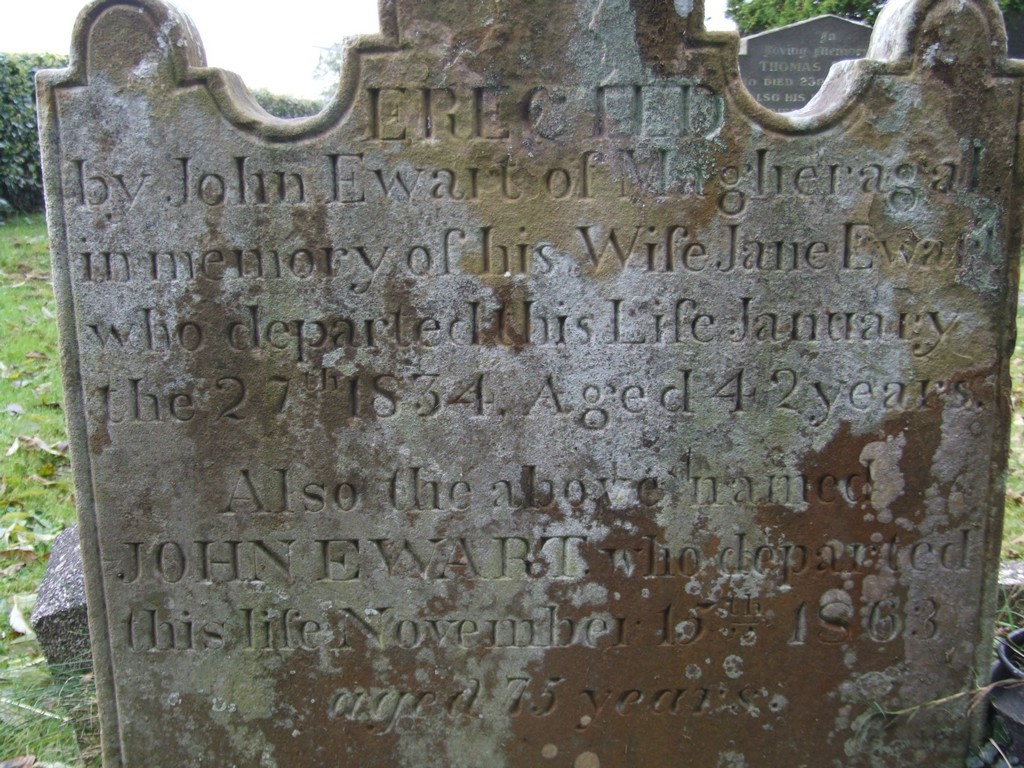

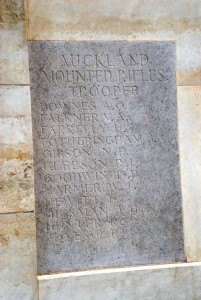

Magheragall is just a church and a hall. There are no houses clustered around it as you might expect in a village, and the front door was locked, but there were the headstones and we examined all of them for Dawsons and Ewarts, eventually finding and photographing all of the ones in Jeanette’s report. The headstone on the left is for my ggg-grandfather, John Ewart who had married Jane Kirk in this church in 1809.

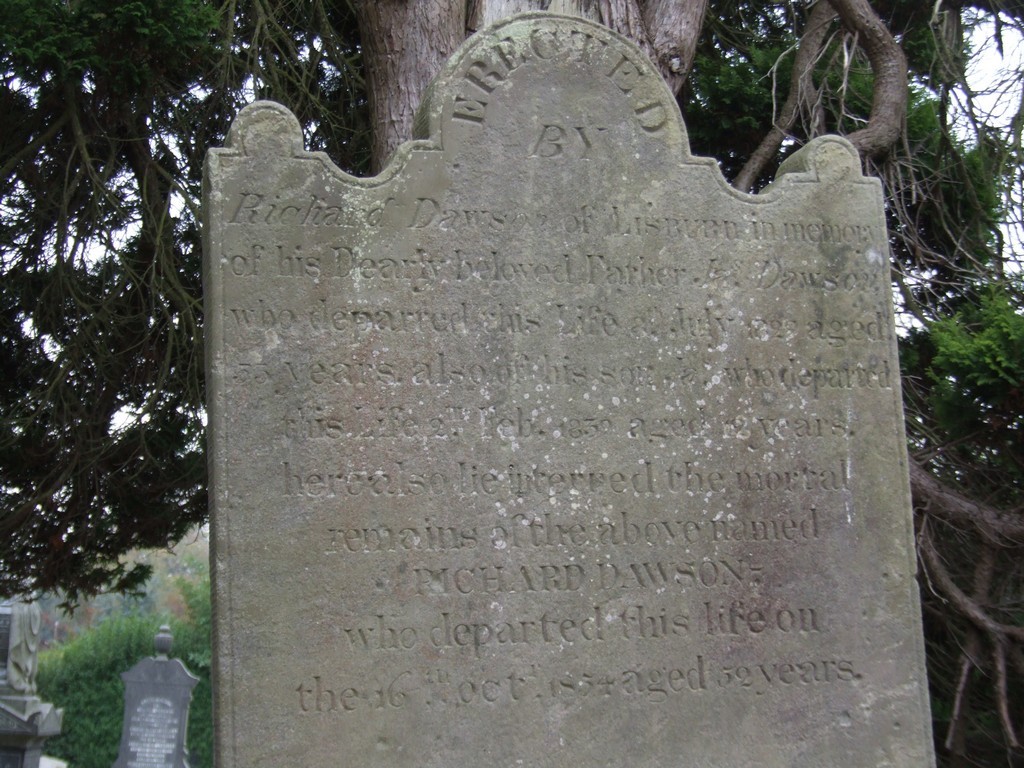

Close to the door of the church was this headstone, right, which the report thought could be my ggggg-grandfather. It lists three generations of the Dawsons of Magheragall: James b1776, Richard b1802 and James b1820. This headstone, then, took my family back to living in this district since 1776

The report wasn’t at all sure who William Dawson 1801-1855 was, in the picture on the left, but he was memorialised along with his wife Jane and two infant children. I had no opportunity to find out where Killultach Cottage was. This is the inscription on the base of the left-hand pot.

The undated and unnamed Ewart headstone, right, is adjacent to John and Jane Ewart’s headstone above. We can safely assume whoever these parents were, they were John’s children and that his grandchildren raised the memorial.

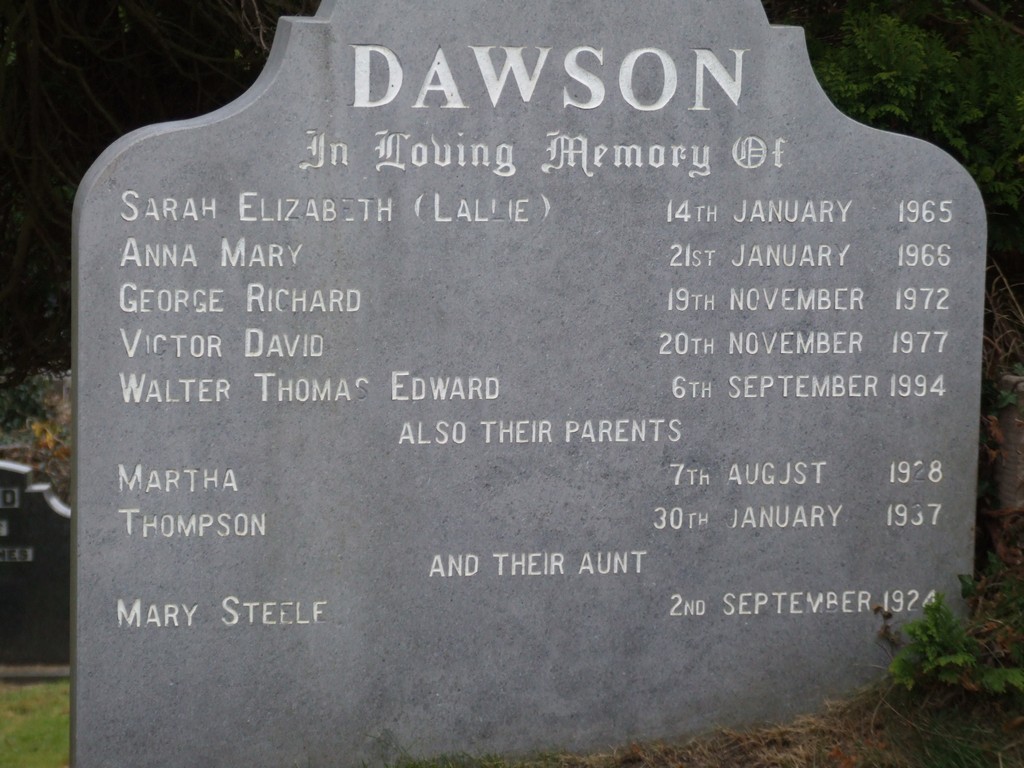

Thompson Dawson, who died in 1937, was a brother of Mum’s grandfather, William 1857. You can see, then, that this family was still in Magheragall until at least 1994.

I don’t know who Thomas Lewis Dawson was, but this grave shows quite an extensive familial pattern in the parish, and also underlines how recently there was Dawson presence in the district. I have no certain knowledge, but it would not surprise me to find Dawsons still living there.

We were intrigued to see this sign pointing down a narrow lane that ran under a disused railway bridge from the road immediately in front of the church. “Her Majesty’s Prison” surmised Elaine. While we were there, several cars ran down the road, or emerged from it.

I stood for a long time reading and thinking about the first headstone we had seen. James Dawson, the father of the Richard Dawson who had erected the headstone, had been born in 1776. Richard had thoughtfully, perhaps even reverently, named his son after his father. Suddenly, the Dawsons had stopped being a mystery; my family had quite deep roots in County Antrim. I wondered where they had originally come from.

Some history from the Linen Building Library

In the Linen Building Library in Donnegal St, Belfast, the following morning I found some of the answers, courtesy of “The Cromwellian Settlement of Ireland” by John P Prendergast, 1922.

According to Prendergast, Henry VIII lost power over the English born in Ireland, and wrestled back control of Ireland by beheading the House of Kildare (English aristocracy) for treason and enacting legislation that allowed only the Privy Council to sign into law any Bills passed by the Irish parliament.

In an area of land in the north, called the Pale, the inhabitants were of English descent, Protestant, and loyal to the Crown. Beyond the Pale, English authority was considerably weaker. Henry sent in loyal English families (Protestant, of course) to own and farm the land and to strengthen his hand. The problem was, since he was himself in a war with the Pope over his attempt at divorcing Catherine of Aragon, and since he had declared himself Protestant in order to sideline the Pope’s authority, he was now weakened in his own authority over anyone still loyal to the Pope and the Catholic Church. In one of those peculiar quirks of history, at that moment a parallel universe was born. Events moved on elsewhere, but the Irish in the north continued with Henry’s War.

He handed the work onto his heirs and Elizabeth 1 encouraged soldiers and “Adventurers” to take up land in Ireland. Prendergast’s appendix showed a James Dawson taking up land as an adventurer in the Baronetcy of Iffa and Offa in about 1640. This district is in northern Tipperary and is close to the border with County Antrim. It would appear he is our ancestor. I didn’t find out anything about the Ewarts, but they probably share the same story, since Ewart is a Northumbrian name, of Saxon origin, living in the Scottish Borders; sometimes English, sometimes Scottish. William Ewart Gladstone, Prime Minister of England, was fond of saying there wasn’t a drop of blood in his body that wasn’t Scottish. I did, though, find a William Ewart and Son Ltd, Flax Spinners, in Ewart’s Place, off Ewart’s Row, off Crumlin Rd, Belfast, in the 1950s. In 1979 the factory disappeared and between 1980 and 1989, the area was allowed to run down. In 1990 Ewart’s Row was no longer listed in the Belfast Street Directory. There is or was (I didn’t find it) a Ewart’s Warehouse in central Belfast.

I was sure that in the report to Jeanette there was an address for William’s brother – somewhere in Belfast. I re-read the report. Richard had joined the Royal Irish Constabulary as a 20-yr old, and so had William, aged just 18½ yrs. He was dismissed in 1881 and arrived in New Zealand not long after. I don’t remember Mum telling me any stories about Richard, but given that William called one of his sons James Ewart Dawson, and that was the name of his immediately younger brother, then William certainly did not forget his family back in County Antrim.

I determined to find the address: 41 Fairview Street, Belfast. Richard had lived there from 1911 to 1925, said the report, as “Richard Dawson R.I.C. Pensr.” I asked the hotel’s breakfast chef where Fairview Street was.

“I don’t know,” he said, “but I’m 1000% certain the name no longer exists.” I went back to the Welcome Centre and the chap there gave me a Belfast city map.

He looked at it very closely, “It’s not here,” he said, “but I’m pretty certain that it was off the Crumlin Road. Go up to the Mater Hospital and ask at the information desk. They’ll know where it was.”

“Crumlin Road? Isn’t that something to do with the Troubles? The Loyalists?”

He turned away. “Ask the Mater, they’ll know.”

An introduction to the Troubles

Outside, it was teaming with rain so we leapt into a taxi and asked him for Fairview Street.

“I’ve never heard of it,” said the driver, “and it’s not here in the directory.” He waved a small, tattered book above his head. We asked him to take us to the Mater Hospital, and he knew where that was.

I asked at the desk just inside the double doors of the entry to Mater Hospital and the lady there said, “It doesn’t exist any more, but it used to be directly across the road from the entrance doors.”

I went back to the entrance doors and looked across the road, but there was only a steel wall. We paid off the taxi and went exploring, crossing the road and going left. A grand neo-Victorian (if there is such a word) chapel sat across the road, next to the Mater. A sign alongside me said Fairview Nursing Home; we were near.

We followed a road between the nursing home on our left and a brick wall on our right and descended a gentle slope that swept off to our right. As the road levelled out, we saw quite a large village green and terraced houses. No trees. Two end terraces had blue pictures on them and one directly in front of us had an orange picture.

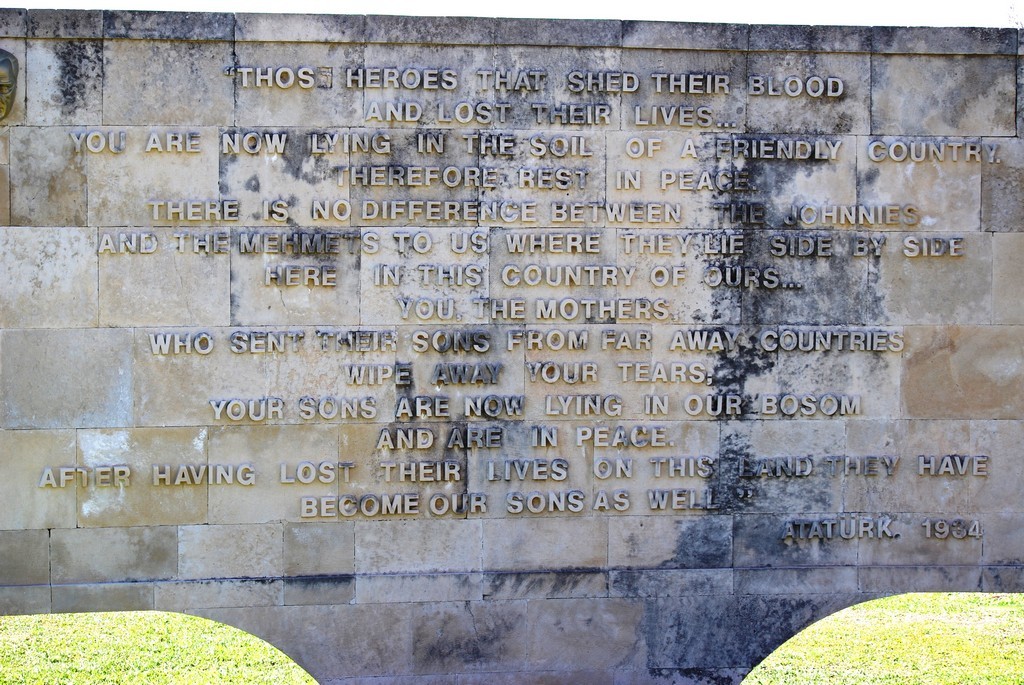

I realised with a sudden chill that the orange picture had two gunmen on it and as I got closer I could see that the whole was a mural, a memorial to a Steve McRea. Alongside the memorial was a modified version of a WW1 anti-war poem that I had grown up with. “Age shall not weary…” I was shocked. Fancy pressing a nearly-sacred work into a turf war such as the Troubles. I walked around the green, wondering if I was attracting undue attention, especially hostile attention, and I hoped my South African hat, and the camera, would provide assurance that I was a visitor. A house was flying an England flag, and the two blue murals were about oppression and ethnic cleansing. It was very intimidating.

A middle-aged man walked across the green and I approached him. “Do you know where Fairview Street was? I understood it was around here.”

He stopped and looked at me carefully. “You see that house with the English flag? It went from there up to the Mater. Why?”

“My great-grandfather’s brother lived at 41 Fairview Street from 1911 till about 1925. He was a sergeant in the RIC.”

“Umm, it’s been gone a long time, but that’s where it used to be, I’m sure of it.”

I turned around and photographed the house with the English flag. The Royal Irish Constabulary had become the Royal Ulster Constabulary and that was the basis of the existing police force in Northern Ireland.

A much older man was walking his dog in the rain. I thought he would know more about the street. Perhaps he had even walked in it. I asked him the same questions.

“Fairview Street? You see that house with the English flag, it went straight up to the Mater Hospital from there. That street between us and those houses was called Old Lodge Street, but it’s not now, and there were quite a few streets that ran from there up to the Crumlin Road.”

I stopped to think. “The Crumlin Rd?”

“Up there,” he said pointing past the house with the English flag.

“You mean the road in front of the Mater Hospital? Isn’t the Crumlin Road something to do with the Troubles? Is it the Loyalists?”

He looked at me in the pouring rain, brushing aside my offer of an umbrella. “You’re standing in the middle of it.” He waited until he saw my face clearing from the shock. “This is called the Hammer.”

“This village green?”

“The Hammer. Your Fairview Street, and quite few others, used to run up the hill to the Crumlin Rd from Old Lodge Road. There used to be hay carts and goods wagons running along Old Lodge Road, but you don’t see them now. The houses there got old and eventually they were pulled down and those new ones were put up in their place, but the street layout was changed to slow down access to the Hammer.”

“And Steve McRea?”

“Oh, he was drinkin’ at the Club just behind us one night and one of the boys pulled out his gun and shot him. That boy still lives here.”

“He wasn’t killed by the Republicans?”

“No! He was killed in a bar-room brawl and I could show you the house of the lad who shot him. He was killed by his own neighbours.”

“How do you feel about these murals? The atmosphere here?”

“It’s a bit much, isn’t it?” he said. “I don’t like it at all.”

I looked at the terraced houses and their pristine white curtains, “This might not be quite middle class,” I said, “but it’s certainly not a slum. I expected the Troubles to be taking place in the burnt-out wreck of a smelly hell-hole. But it’s quiet and there are children being taken for walks.”

I stopped as Elaine joined us and he was happy to share her umbrella. “There is a sign beside the Steve McRea mural that says ‘Anyone caught defacing Loyalist murals will be seriously dealt with’ how do they feel about that?”

He tapped a cream brick wall we had been sheltering beside, “There used to be a mural on this wall, but the new owner came out one morning and painted it over. There was a bit of a fuss, but nothing much. More mutterings than actual talk. If you can’t sell your house, you have to redecorate it.”

“Do you think the Good Friday agreement has finally settled the Troubles?”

“Once Ian Paisley joined the party, the Troubles were over.” He paused for a moment and whistled up his dog. As he climbed into his car he added, “If Tony Blair hadn’t gone to Iraq, this might have been his finest hour.”

I showed Elaine where Fairview Street used to be, using the house with the English flag as the marker. “My great-grandfather William, and his brother Richard were both in the Royal Irish Constabulary,” I explained. “Richard lived here, off the Crumlin Road in the very heart of the Troubles. How much and what sort of a role did he play?”

Elaine murmered quietly through the purr of the rain on her umbrella, the water glistening grey on her cream coat. “William had a job in the RIC in Sligo,” she said. “Jeanette said he was dismissed very young and shortly after went to NZ. I wonder why he was dismissed? Did he say yes and do something terrible, or did he say no, and they fired him for that?”

We roamed the nearest houses, documenting the murals. A small group clustered under their umbrellas and examined a mural of a Royalist soldier being comforted as lay dying, with his spirit on a white charger dancing on the water, in a hurry to leave and claim his reward from God.

A few thin trees waited, leafless, for spring.

The primitivist murals with their emotional re-writing of history and violent appeals against ethnic cleansing were nevertheless sobering and even intimidating.

On one wall, a severed and bloody hand crawled ashore with Viking warriors in the background cheering it on as they prepared to land in their fighting ships. The Red Hand Brigade was pictured everywhere.

It must have been a comforting thought for the locals that they were protected by such a malignant force, or perhaps it was one of the methods used by the force itself to ensure compliance and silence from the homedwellers.

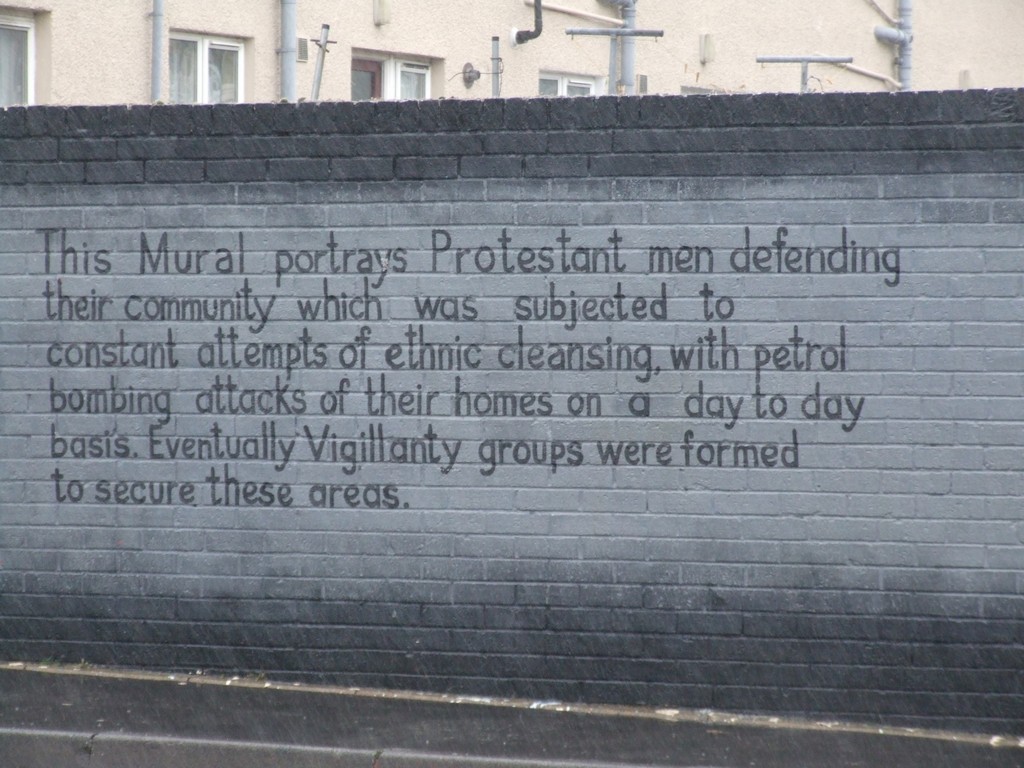

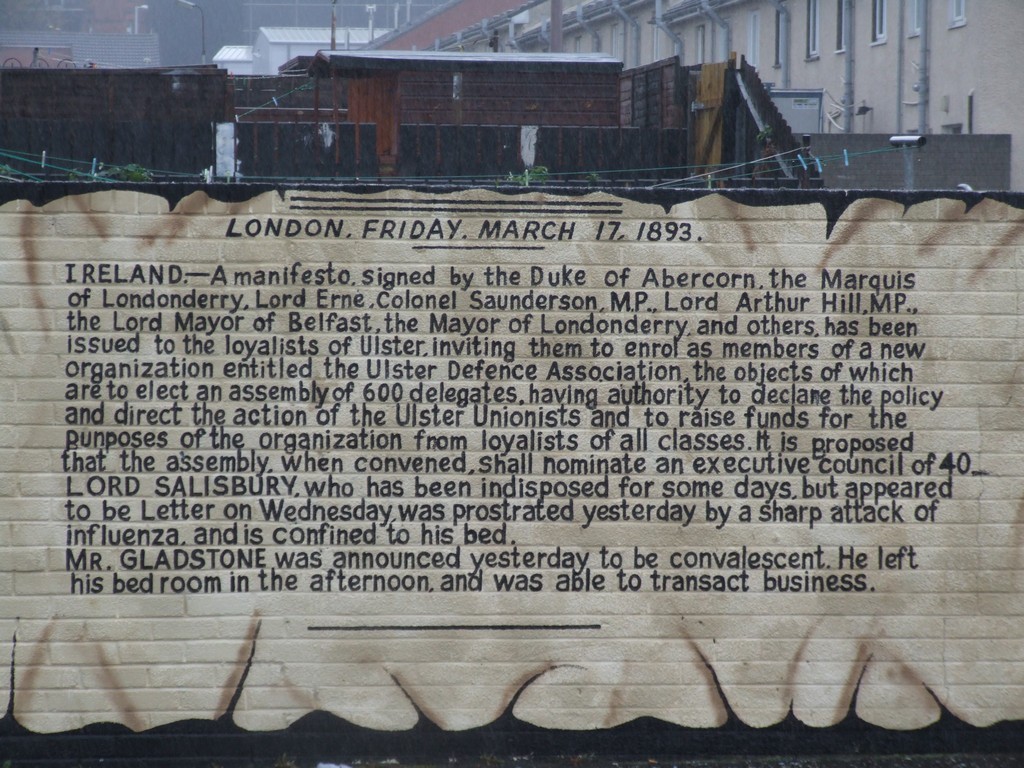

The story on the painted brick wall below accompanies the mural on the house alongside. They claim they are being attacked on a daily basis and that’s why they have had to set up the Vigilanty (sic) groups to defend themselves.

The scroll alongside the picture of the burning terrace houses quotes the Belfast Telegraph: “Several hundred familys were forced to flee their homes last night as houses came under attack from republicans. The number of homeless is running into Several thousand, more people were moving out of riot areas today. The women and children have been offered shelter in Cities across the world. Security forces moved in to bring calm to riot areas.”

Below is an end of terrace mural showing the development of the Ulster paramilitary forces. The figure in the middle top, in the balaclava, is the pinnacle of that evolution.

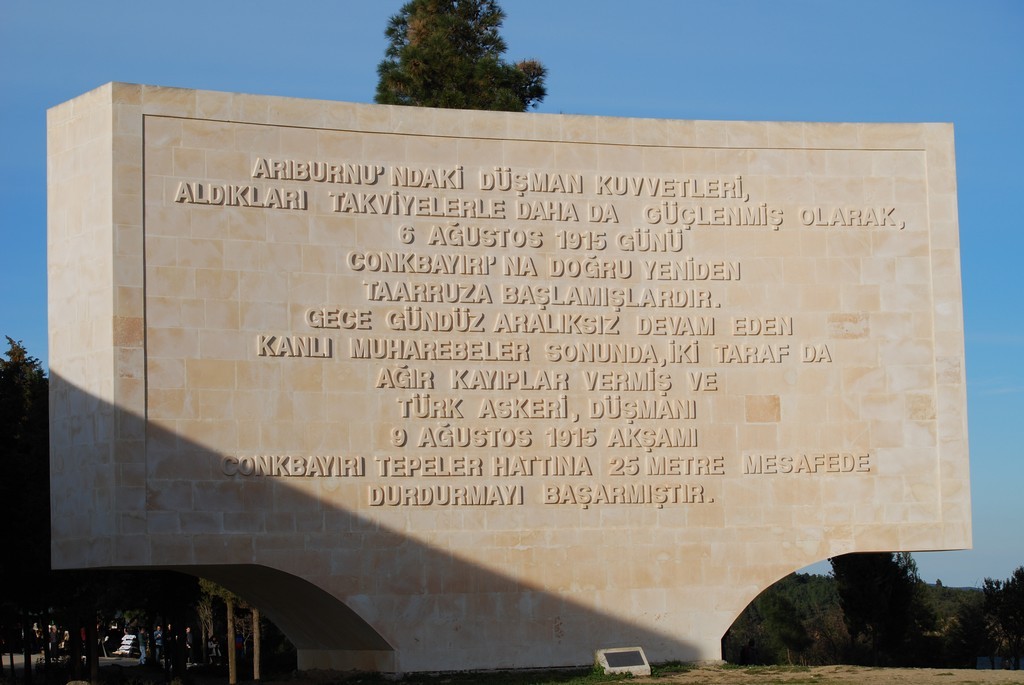

This last pair of pictures shows a painted brick wall that explains the establishment of the Ulster Defence Association.

I am not familiar with all the symbols on the house below, but I recognise H block from the Maze prison, just outside Lisburn. It was almost exclusively Catholic prisoners who were held there, so I am unsure of the message of this mural.

We decided that we were wet enough and cold enough, and that our cameras had taken a sufficient beating, for us to retreat to the city by taking a bus from near the Mater. We walked back to the Steve McRea house because it looked as though that street led back up to the Crumlin Rd. I stopped a postie, “The building with all the pillars on the corner up there?”

He looked up the hill.

“Do you know what it is, please?”

“It was,” he said with heavy emphasis, “the Crumlin Rd Courthouse.”

“It’s pretty posh, isn’t it?”

“It’s not used now. And no-one’s bought it. As part of the Good Friday Agreement, they gave up using this courthouse and only use the one in town. They used to try prisoners in the courthouse and then take them by underground tunnel to the prison.”

“Prison?”

“Do you see the chimney? It belongs to the Crumlin Rd Gaol. They used to hold mostly IRA prisoners there. Mind you, Ian Paisley was there for a while.”

“This is a loyalist area but they held IRA prisoners in the local jail?”

“It’s closed now, too – part of the Good Friday Agreement – and they are trying to turn it into an arts centre with caffs and such-like. The prisoners from here all went to a new prison in Marghaberry.” He paused. “Mind you, most of them aren’t prisoners any more, either.” He pedaled off.

The Crumlin Rd Prison. I’d heard stories; they were dim echoes of violence, contempt and political manoeuvring.

I remembered Marghaberry; the side-road going under the bridge opposite Magheragall Church. Elaine was right.

We walked up the hill and I photographed the prison building before we crossed the road to see it more closely, and to catch the bus back into the city. It was at once menacing and beetle-browed but at the same time massive and self-assured in its Victorian brownstone solidity. It was like Mt Eden Prison – heavy and overpowering and yet, now that it is vacant, it’s not something that should immediately be destroyed. It has its own organic beauty. A perfection of form and function.

Was the chimney solely for coal-fired heating?

The courthouse building opposite, with its grandiose statues of British Justice, looked faded and care-worn. Why was it not possible to sell it, or to buy it? Perhaps the weight of its history was crushing the very stones it was built from. Too pretty, too colonnaded, too self-important; a busy modern world wants nothing of it.

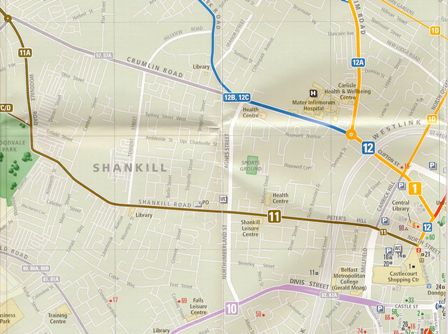

On the bus, I took out the Belfast city map that the man from the Welcome Centre had given us and we had a look at where we had just been. I have reproduced a small portion of the map and you can see Belfast city is bottom right, so this area of the Troubles is west and north-west of the city. The Crumlin Road runs west, along the blue route for a while. Immediately above it on the extreme left of this map is the Boyne. You remember the battle of the Boyne. King James 1 (of the King James Bible) won a famous battle for England here and ever since the Loyalists have been indulging in marching celebrations in full summer. The brown road is the Shankhill Rd and it marks the boundary between the Protestant Loyalists and the Catholic Republicans. South of the Shankhill Rd to the purple Falls Rd is the Belfast Republican stronghold. Two adjacent neighbourhoods who refused to get on.

The Mater Hospital is shown on the map, but not the Crumlin Rd Gaol. I couldn’t help thinking – what was Richard doing all this time? For ten years or so he lived in retirement on Fairview St, in the very heart of the Troubles. His job as a policeman would have brought him into daily contact with both sides. Probably in conflict, also, with both sides. How did he cope? What did he do? What did he think? Did he work for peace?

Still a little shocked but without doubt very wet and quite cold, we called in to a little cafe alongside a row of bus stops and in full view of the Town Hall. We had to share a table and some beautiful leather loungers with an attractive young girl in a blue dress who said she was at Queen’s University. “So you have a genuine local accent?”

“I come from just out of Belfast, but I think it’s pretty close,” she grinned.

“Is it holiday at the moment?” Elaine asked. “You’re not in class.”

“I don’t always attend class – I also do charity work, helping others cope and giving them counselling. I don’t work for money.” She stood up and brushed the crumbs of her dinner onto the floor. “God provides,” she said with breathtaking innocence. “I never go hungry. And I always have a roof over my head.”

I turned around as she left. A young goth, whom I had noticed arriving, had been joined by what looked like his mother and some of her family. So goths have mothers.

I couldn’t resist. I walked up to the group and asked if I could take his photo. He nodded. They were intrigued. I took the photo and they saw the result in the camera viewer. The sky blue background and the shy young goth with his tattoos, black clothing and facial piercings were all so much in place in a major European city. After the head-turning madness of the Troubles, normalcy seemed so refreshing.

The crumbling of Fairview Street

I felt that I had one more job to do, so I returned to the Linen Centre Library to see what I could find out about Richard’s stay at 41 Fairview Street, and then to see when and how Fairview St ceased to exist. The tousled-headed, skinny young man on the library desk waved me through, recognising me from the previous visit. I took the 1901 Belfast Street Directory from the tall glass cabinet and hefted its bulk onto the oaken table where I had sat last time. The directories were tattered and time-worn, but most of them were there, judging from the dates stamped on the leather bindings of their 4” wide spines. 41 Fairview St was easy to find, since all the streets were listed in alphabetical order. After I had tried a few books, I could open them at about 1/3 of the way in and turn just a few pages to get to Fairview St. Richard wasn’t there in 1901, so I skipped to 1905 and he wasn’t there, either. Then, in 1910 there was this entry:

Fairview St

41 Dawson R RIC pensr

I checked every year and he was there until 1920, when I noticed that his neighbours had changed. Perhaps they hadn’t, but I saw the kinds of people who lived around him. At 1, 3 and 51 there were other RIC men, and I discovered it was quite a short street, too, because the numbers went from 1-51 and that included both sides of the street. There was a slater, a carpenter, a grocers asst, a shopkeeper, cattle dir (drover?) and a waiter. He was there in 1922 and all the way to 1925. In 1926 I noticed there were policemen at 1, 13, 19, 51, 6 and 8. He was there still in 1927 and then the entry changed for 1928:

41 Dawson Mrs Mary Jane

Was that his wife or his daughter-in-law? The 1929 directory was missing but the entry for 1930 was the same as for 1928. In 1931 the directory noted:

41 Short Wn Gardener

Perhaps Mary Jane was his wife and she, too had died.

I skipped to 1965, and all the properties from 1-51 were occupied, so I skipped to 1975. By this stage it had a British Post Code: BT13 1AU, but the listing was quite ominous: 1-53 were vacant and 2-56 were vacant ground. I took this to mean that all the houses on one side of the street were derelict and no longer inhabited, if even habitable, and that all the other side of the street had been bulldozed. In 1976, all the lots were vacant, again in 1977, again in 1979 – and then in 1980, the street name itself was missing from the directory. Fairview St was gone.

I showed my notes to a tall, greying man who had been ferrying books to and from a shelf not far from me, his green trousers and harris tweed jacket catching the corner of my eye as he moved about. We could have been in London, rather than Belfast. “What’s that all about? The vacant houses and then the vacant land.”

“Three kinds of relocation,” he explained in the kind of accent I had heard from Ian Paisley on the television. “You could volunteer to relocate and you’d get a new house somewhere else: you could get burned or bombed out of your house and the aut’orities would find a new one for you: or you could just go somewhere else and leave the whole thing behind.”

“Like New Zealand, or New York?”

“Precisely.”

And do you think of Northern Ireland as Ulster?

“Ulster and the Loyalists? The first thing they wanted was Home Rule because they didn’t want to be run by an absentee government in Westminster. Then when it came near, they realised that Home Rule meant being run from Dublin and they decided they didn’t want that, so they made it look as though the British Government was pushing them out of Britain, where they rightfully belonged. So now they wanted local rule, and they appealed to an area called Ulster as their homeland. Thing is, Ulster includes counties in Ireland, and Northern Ireland has a different boundary from that which would correctly be Ulster.”

“They just made up the rules as they went along,” said a much shorter man who had joined us “and took whatever suited them.”

“Calling themselves Ulstermen suited their political purposes,” said the first man tiredly. “I’m glad it’s over. Look how the city is prospering.” He looked again at my notes, “Fairview St? Off the Crumlin Rd?” I nodded.

“There is a long stretch of the south side of the Crumlin Road where they cleared away everything. But first they had to vacate all the houses. Leaving them to rot was the perfect way of clearing them out.”

He moved off. They had finished talking to me. I could feel that they had generated quite a bit of passion, and I thanked them and left.

The young man at reception nodded as I dropped off my pass.

The wounds are still raw. The hurts still hurt, but the citizens of Belfast warm to the present, look to the future and turn their backs on their violent past. The parallel universe has finally converged and Henry’s War is over.

Ewart Tearle

May 2008