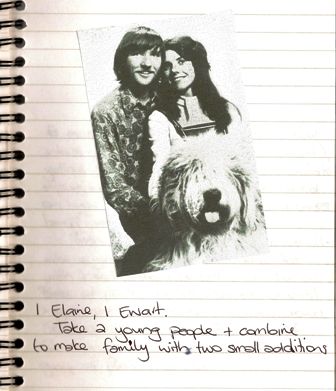

The Empire Hotel – A Railway Story

By Ewart Tearle Nov 2009

I lived for 6 weeks during the Christmas Holidays in the now-burned down Empire Hotel in Frankton, near Hamilton, New Zealand. I can’t remember how much it cost, but at the time, I was earning £5.0.0 a week working as a yardman for Caltex, the oil company, that had three tall storage tanks alongside the railway line. I have a vague idea that the hotel charged £1 a week and I kept my costs down by having only fruit for lunch, at about 1/-, and fish-and-chips at about 2/- for dinner, giving me a profit for the week of about £3. This was the most money I earned until I was a second-year teacher some five years later.

In the Caltex yard, there was one tank for diesel, one tank for regular petrol and one tank for super petrol. My job was to dip the tanks every two hours and let the office know the level. Every few days a tanker or two would be dropped off by the shunters on the siding adjacent to these storage tanks, their appearance triggered by the dips I had recorded. It is a peculiarity of railway stock that they look unhappy and bedraggled if they are sitting waiting, so while they were there, I would dip the tanks again and again until I knew that there was room in one of the tanks for the entire quantity of the fuel in at least one of the tankers waiting to be unloaded. Dipping was easy – I climbed the ladder attached to the outside of the 50-foot tank and looked at a small wooden stick poking above the curve of the tank top. There was enough room in the tank for the contents of at least three tankers, so it was hardly a difficult task. If the top of the rod was six inches or more higher than the hole into which it was fitted, then I could see the collar that stopped the rod from disappearing into the tank, so there was more fuel to be used before it was safe to add an entire tanker. If the collar was nestling into its socket, I would draw the eight-foot rod out of the tank and ensure the last bit of the bottom of the rod was dry. Now I could re-fill the tank. Each of the huge storage tanks had a long metal-reinforced hose attached to the bottom of the tank and the other end I unwound and attached to the tanker, turning on the tap at the same time to allow the fuel to flow. Between the hose and the tank inlet there was a tap that, when turned, automatically started an electric motor that forced the fuel from the tanker into the bottom of the tank. When it sucked air, it turned off. If the yardman got the dip wrong and started the upload, there was no way to stop it. Once the tank filled up, the rest of the fuel overflowed. Each tank sat in a high-walled hollow big enough to take its entire contents, to cope with just such an occurrence. I heard that one yardman had emptied the contents of the diesel tanker into the super petrol storage tank – and to compound things, it overflowed by several hundred gallons. That’s why I was the new yardman.

The hotel served only one meal, breakfast. It was interesting…. The cook was a great guy – huge, bald, loud, dressed in a white singlet, canvas trousers and black boots, sweating all the time. He had one of those distinctively rugged New Zealand names that I wished so badly my mother had called me – something like Bruce, or Jim, or Jack. Of course, the inmates of the hotel had lots of adjectives they went through before they got to his actual name, but they certainly seemed to like him. He cooked a wadge of bacon, and a bucket of sausages, in a yard-wide cast iron frying pan over a red-hot coal range, and threw sliced onions into a smaller frying pan alongside. The eggs he cooked by breaking them directly onto the fiercely hot range-top. The under-cook passed him tin plates hot from the oven and he slapped some bacon, a couple of sausages, onions and an egg on each plate and then whacked it down on the counter, swinging it along the shiny surface until the man at the head of the breakfast queue swept it up before it hit the floor. You could hear each man take the plate and swear at how hot it was as he carried it back to his table. They seemed to know a lot about the ancestry of the cook.

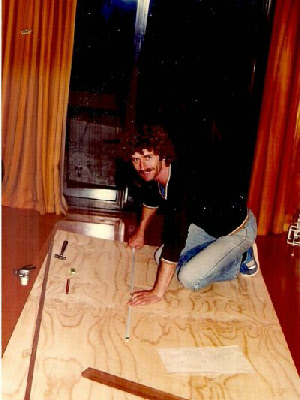

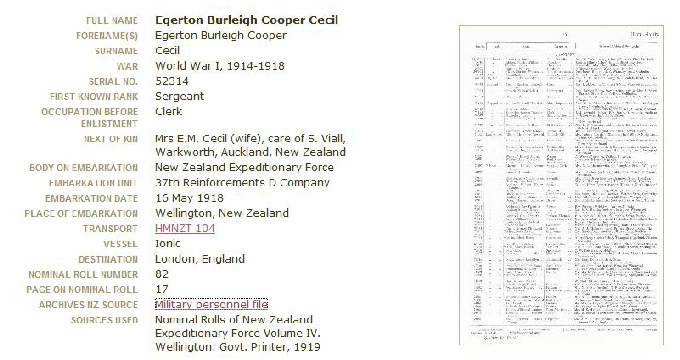

We all sat down within half an hour of 6am, or else we got no breakfast, sitting on assorted wooden chairs around equally mismatched round, square and oblong, bare wooden tables. A wooden floor of 12” oak planks spoke of the former grandeur of the hotel, but grimy windows and dark stains in the wood told even more about its fallen present. I suppose there were thirty of us. Wizened little men from the First World War dressed in cloth caps and harassed tweed jackets with woollen singlets exposed under threadbare blue-grey shirts sat in silence and shovelled the bacon and eggs from their tin plates into their thin, sometimes twisted mouths. They were tiny, like my grandmother, who fitted under my arm when I held it out horizontally. How on earth had they won a war? They looked straight ahead; old, tired and sick, their eyes full of nightmares. Railwaymen in dark overalls ate ravenously and drank their hot, sweet tea from squat china mugs they would thump onto the table between mouthfuls of bacon and sausages while they laughed, gossiped about each other and told filthy jokes. They were taller men, bigger, some with paunches that forced their belts to cut into their middle. They had one of the most dangerous jobs in New Zealand, because at shunting time, it was they who ran between moving railway rolling stock, coupling or decoupling on the run, jumping off and onto a step welded near the rear and front of all the wagons. They would stand beside the wagon to be attached and would wave the shunter forward until it clacked against the coupling unit. If the lock didn’t come down, these men would jump into the gap between the wagons and drop the lock, skipping backwards to clear the still-moving stock and jumping onto the step. The shunter was in a hurry – the engineer had to fend for himself. I saw the force that the shunter sometimes used when coupling, and it had torn the heavy cast iron fist of the coupling unit on the wagon into a grisly twisted hook. When a wagon was decoupled, the shunter gave it a thundering whack and the wagon, with all the other rolling stock in front of it, clattered coupling irons together and charged forward. The engineer on the ground raced along the track to push a lever so that the cortege of rolling stock was diverted to its resting place for the day. If he failed to reach the lever in time, the first wagon passed onto a portion of the track that was not intended for it, and the engineer could only stand in frustrated impotence while he waited for the stock to stop rolling, or crash into a terminal barrier, and the shunter driver yelled curses at him that would have split the heavens. That short train of stock moved very quickly and in total silence. In the fog that often afflicted Hamilton, and in the rush to get all the wagons in the right places for the day, a man could easily be in front of the onrushing freight and die without ever knowing what hit him. The men at breakfast were loud and violent-tongued in an effort to remove the thought that today’s fog might be the last thing they ever saw.

One or two men worked in local car garages and one I knew of worked in a metal scrap-yard, but most of these men were working on the railways.

My bedroom was on the second floor and overlooked the railway shunting yards at the back of the hotel. An iron-framed cot with a wire base slung like a hammock supported a kapok mattress, and a smelly, stained pillow which rested in the right-hand corner under the only window. A small, pale green four-drawer dresser left a narrow path to the bedside table with my shiny, chrome-plated alarm clock the only ornamentation. A rimu wardrobe filled the last cavity in the floor space on the left-hand side of the door and a 40-watt light bulb hung crookedly from the ceiling on fraying wires. I could see faint colours and shapes in the aged wallpaper that might have been tales of far-away lands, in ancient times, but nothing I could turn into any sort of sense. The “ablutions room” was at the end of the corridor when I turned left from my door, while the kitchen was to the right, and down two sets of creaking wooden stairs. There was no key for my bedroom, and I never had enough money to replace the awful pillow. I used my eiderdown on the wire base to put some body into the mattress.

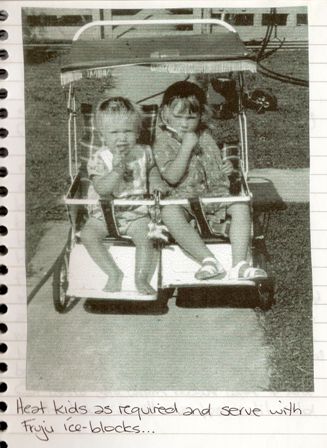

Across the tracks, there were wooden cottages built for the working class, originally painted white, but when I was there they were down-at-heel with rusting corrugated iron roofs, unkempt lawns, cracked windows and un-sealed roads. In the summer they summoned dust devils and in the winter, they were awash with mud. This was the Frankton slum and it nursed a generation of screaming, much-abused, much-maligned young mothers with grubby, shabby kids. Work for post-war men was not always close to Frankton and these young women could find themselves without their men for long stretches, and most likely penniless until the men arrived back with whatever was left of their pay. The howling kids and their screaming mothers – even late into the night – was what I heard most from the other side of the tracks, through the window of my bedroom on the second floor of the Empire Hotel.

On the railway, the drivers and engineers yelled orders and banged trains together all night long, but no more energetically than at eight o’clock in the morning when everyone in Frankton had to cross the railway line to go to work in Hamilton. At that hour of the day there was always a train (or two – it was a dual line between the station and the shunting yards) across the only level crossing on the only road to Hamilton. Even in the sixties, the days of steam were behind us, and these trains in Frankton were all diesels. I stood once by the tracks in Rotorua watching the billowing white smoke and listened to the chuffing and animal breathing of the one steam loco I ever saw pulling a train from Rotorua over the Mamaku Ranges to Hamilton. When I was in high school, Aunty Grace had sent me back to Rotorua from the mining village of Pukemiro deep in the Mamakus on a steam train consisting of a couple of carriages immediately behind the engine and nearly a mile of freight and empty wagons behind. Fire and sparks leapt from the funnel and fell on the dry grass alongside the railway track, setting fires every few hundred yards. White smoke tinged with black shadows writhed from the engine, through the carriage and down the length of the train. The huge black engine in front of me seemed to be straining every muscle, breathing deeply and sighing heavily like the draft horses that pulled pine stumps from hedges on the farm my father worked when I was a pre-schooler. The smell of coal smoke, leather and old timber in the carriage was deeply impressionable. The sense of going on an adventure with a rumbling giant was palpable. There is no romance like that, in diesel.

“Dirty bloody things,” my mother said with considerable feeling. “You’d put a full wash of clean clothes on the line, and some smelly damned train would crawl past and leave clinkers all over the washing. At least diesels are clean.”

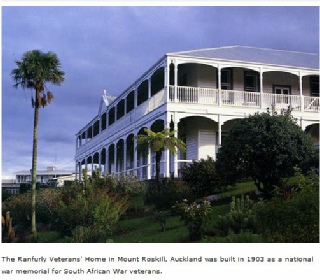

The hotel – more a boarding house, in the way it was run – was an elegant, three-storey wooden structure clad in weatherboard. It was quite a handsome, turn of the century building painted green and white with a large gold sign, outside staircases, steep roofs and an imposing turret. But it had seen its best days. The green was faded, the white was dirty and the sign was cracked and had bits missing. The stairs creaked, the roof leaked and the manager put his head to every door in the hotel to assure himself there were no girls in the hotel after nine PM. In fact, women were not allowed in the hotel in the day-time let alone stay overnight. Frankton was a down-at-heel railway town and the hotel had A Reputation; the manager was determined to stamp it out.

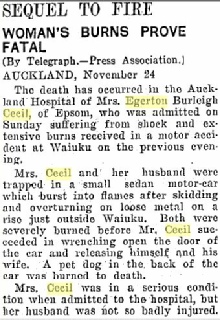

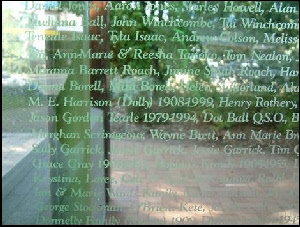

I suspect (as did the local press) that a disaffected Lothario burnt the hotel down when his girlfriend was discovered under his bed. The tragedy was that he killed six in the attempt to exact his revenge, and he will be in prison for some time.