During 1914 the family lived at 1 Montague Street, Newton, Auckland. Egerton was working for the New Zealand Railways.

Sadly in 1916 things got rough and Egerton was convicted of assault and sentenced to six months hard labour in Auckland. Due to circumstances the children were taken from Egerton and Catherine and became wards of the state. Egerton and Catherine separated under difficult circumstances.

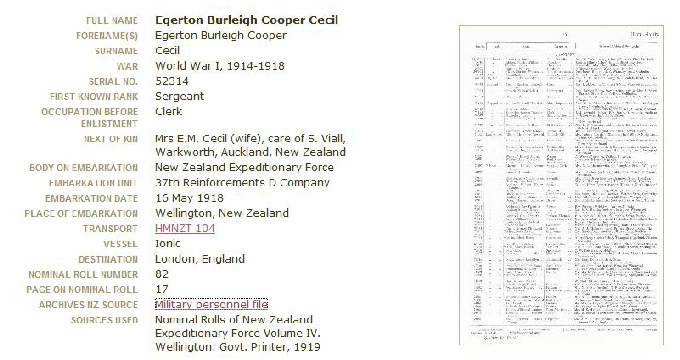

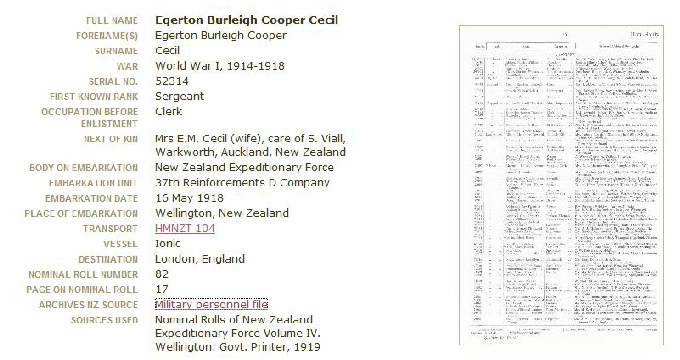

Before Egerton left for war in 1918 he married Edith May Viall (who already had a young daughter called Lily) and they lived together in Mahurangi, Rodney, Auckland. Egerton was working as a clerk.

Egerton embarked on the 16th May 1918 at Wellington, New Zealand.

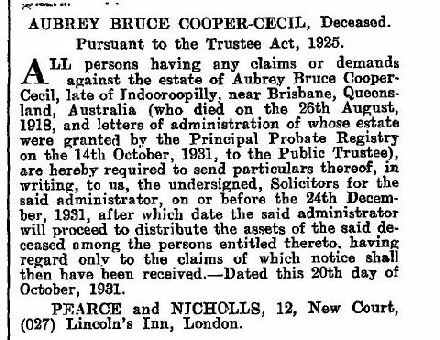

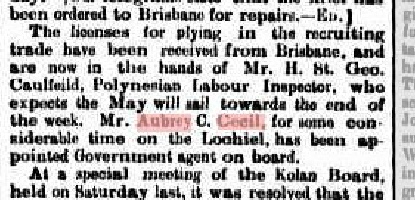

While he was away at war his brother, Aubrey Bruce Cooper Cecil, died in Brisbane, Australia.

WW1 as a New Zealand Soldier

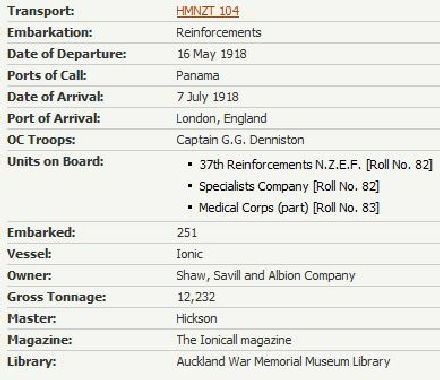

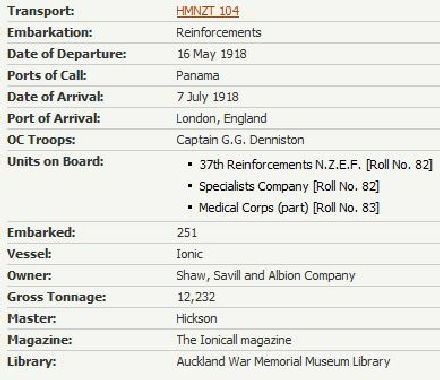

The Ionic, one of the ships used in the transportation of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force to join British troops in WW1.

The cover of the on-board magazine and the details of the transportation.

The following is sourced from Egerton’s WW1 Medical Files:

5 November 1918 Injury to his right ankle while in France when his trench was blown in by a shell explosion.

28 November 1918 While he was in hospital he developed influenza.

10 January 1919 Medical notes from NZ Command Depot, Codford, Wiltshire, England 2 month med cert.

9 April 1919 HMNZTS Paparoa, 3 month med cert.

24 June 1919 Certificates sent from Sick & Wounded records to Base records.

20 August 1919 Letter for report of medical prognosis from military base.

7 October 1919 Auckland base, 3 month med cert.

We have no record of when he became a sergeant.

It is noted however, on Egerton’s medical records that he was wounded on the 5th November 1918 in France. It is possible that he was involved with the recapture of the French town – Le Quesnoy.

One report says:

“As recently as a week before the Armistice, on 4 November 1918, New Zealand troops had been involved in the successful recapture of the French town of Le Quesnoy. The attack cost the lives of about 90 New Zealand soldiers – virtually the last of the 12,483 who fell on the Western Front between 1916 and 1918.”

New Zealand had the highest per-capita loss of any nation involved in WW1.

Another report notes:

“Just a week before the end of the First World War in November 1918, the New Zealand Division captured the French town of Le Quesnoy. It was the New Zealanders’ last major action in the war. To this day, the town of Le Quesnoy continues to mark the important role that New Zealand played in its history. Streets are named after New Zealand places, there is a New Zealand memorial and a primary school bears the name of a New Zealand soldier. Visiting New Zealanders are sure to receive a warm welcome from the locals.”

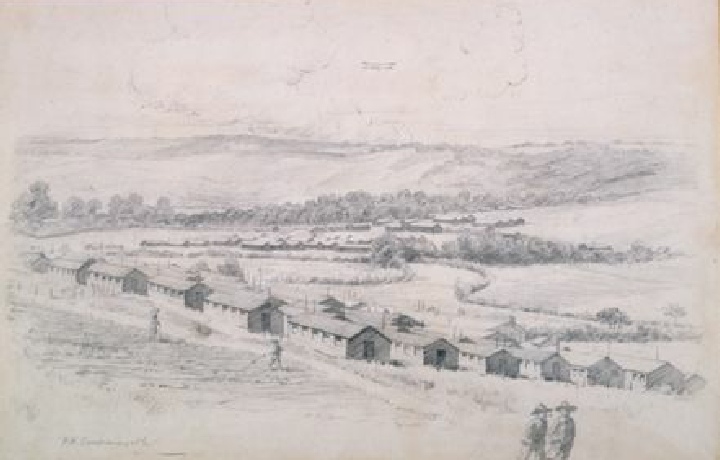

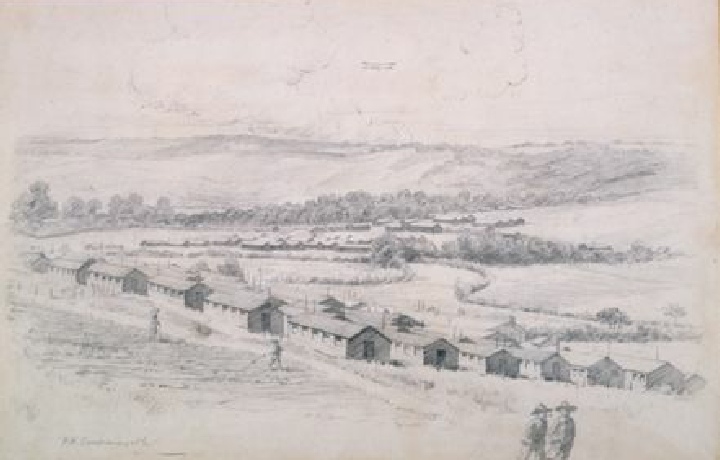

The War Effort of New Zealand; The Codford Depot

New Zealand Command Depot, Codford (circa 1918)

To give you a little flavour of the times, above is an illustration of the NZ command depot, Codford, pictured in the War Art archives

… when the wounded or invalided soldiers were sufficiently recovered to leave Hornchurch, they were sent to the Command Depot at Codford to be “hardened” for further active service training.

… This, also, was the first stage on the return journey to the trenches.

Life after the War

After Egerton came back from the war, he moved with Edith May and her daughter Lily to 9 Edgerley Ave in Epsom, Auckland. The house has since been demolished to make way for what is now the Newmarket overpass for the motorway.

Egerton became a motorman and worked for the Transport Board. They had two daughters together, Thelma and Winifred (pictures at end of Egerton’s story).

Egerton and Edith May Cecil

Egerton’s mother, Elizabeth, was living with the family in Epsom when she died in 1929. She is buried in an unmarked grave at Waikumete Cemetery, west of Auckland.

The unmarked grave in Waikumete Cemetery, Auckland, of Elizabeth Cecil nee Peadon, Egerton Burleigh’s mother, is in the very foreground of this photo.

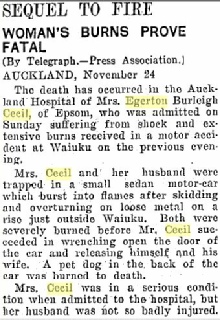

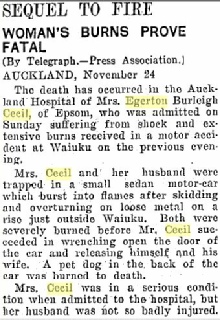

It was only four years later when sadly Edith May Cecil died in a car accident in November 1933 in Waiuku, south of Auckland. Edith is buried in Hillsborough Cemetery in Auckland. Her grave is covered in burnt shells.

The desperately tragic story of the death of Edith May Cecil is told in these three pictures.

Edith’s grave

Detail of Edith’s headstone

After the death of his first wife, Egerton lived alone at their house in Epsom. Then in 1944 he married Cassie Carter Dent (nee Natzke), who already had two children – Frank and Evelyn. Cassie was the sister of renowned opera singer Oscar Natzka; a brief biography is planned.

By 1949 Egerton and Cassie had moved to Te Mata near Thames. Egerton was retired but it was not long before they moved back up north to 6 Sidmouth St, Mairangi Bay in Auckland.

Together they lived there until Cassie died in 1962. His granddaughter Ninette remembers visiting him, his ankle always gave him grief and she remembers his limp.

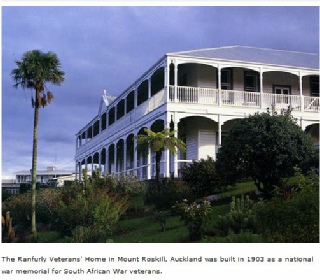

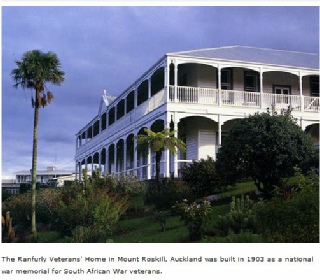

Egerton’s last move was to the Ranfurly Veterans’ Rest Home in Mt Albert, Auckland.

Egerton Burleigh Cooper Cecil died of Myocardial Degeneration on the 28th February 1967.

On his death certificate it says that he was cremated at Waikumete Cemetery. They have no records of this so we don’t know what happened to his ashes, or if indeed he was actually cremated there.

Ranfurly veterans home, Mt Roskill, Auckland, New Zealand

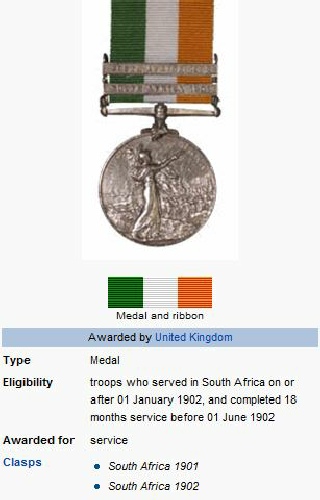

Egerton was a true Anzac soldier. He fought in the Boer War as an Australian soldier and in WW1 as a NZ soldier and in WW2 as an Instructor.

Egerton Burleigh Cooper Cecil 1881 – 1967

Egerton’s children

Burleigh Victor Cecil Tebay (Vic) with his wife, Beatrice

Melba Doreen (Dolly) Hare

Lil and Joe Sunich

Winnie McNae and Thelma Barnie

Footnote

‘Aubrey’s Sons’ has been compiled by Wendy Skelley in New Zealand, 2011 (wendy.skelley@xtra.co.nz)

Thanks to Egerton’s granddaughters Ninette Skelley and Lorraine McNae for some background details and photos, Herbert Rogers for his amazing Boer War details and photos, Barbara Tearle for the ‘A Victorian Mésalliance, or, Goings on at the Manor’ and her inspiration to carry on the story and most of all a big thank you to my life-long partner, Tony Skelley, for enduring the hours while I tippity tapped away.