There were three great slums in Victorian London, perhaps the worst slums in the whole world; Spitalfields, the Mint and St Giles-in-the-Fields. I have mentioned St Giles before, perhaps a mile from Holborn, behind CentrePlace. Mint St was the area around the Southwark fire station, literally the site of King Henry VIII’s mint, just behind Union St, and the Spitalfields slum was the Bethnal Green/Shoreditch area to the east of Shoreditch High St. This particular slum was described in 1845 as having “the most intense pangs of poverty, the most profligate morals, and the most odious crimes (which) rage with the fury of a pestilence.” Into this mix of poverty, low morals and crime, throw in a nice money-making scheme supplying bodies to the local hospitals so that they could teach anatomy, and you would generate one of the most disgusting and disturbing crimes humanity could dream up – body-snatching, in this case, for profit.

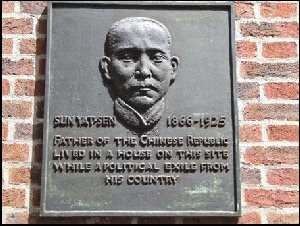

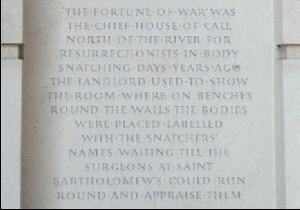

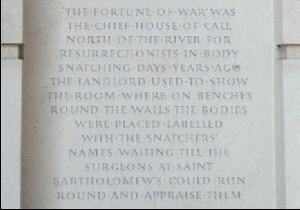

Sign in Giltspur St, Smithfield

The sign above is in Giltspur St, opposite St Bartholomew’s Hospital. It tells the story of the Fortune of War pub, in which bodies were laid out so the surgeons from St Bart’s could select and pay for the ones they wanted. I often wonder how the surgeons of St Barts these days deal with their consciences when they leave work through the exit that faces this sign.

The men who carried out this skin-crawling, “trade” were variously called Resurrectionists (guess why!) or body snatchers. They would hang around looking for funerals and then the night after the ceremony they would lift the body, strip it, drag it on a trolley through London to their markets, sell the body, and then sell whatever useable clothes and jewelry the body might have possessed. There are also stories of lifting the flagstones in churches and replacing them carefully, so the families never knew the body had been removed.

Most of the churches of London had graveyards, and the graves were almost always shallow-dug. It was the work of an hour or so to remove a body from its coffin and supply it to the nearest paying surgeon, replacing the flagstone as they went. You can see in this picture I took in St Bartholomew the Great, that the caskets were buried very shallowly – the gap in the clay is the lead from the casket. There are stories – and some convictions – of gangs who supplied freshly murdered bodies, but I know of no surgeons who were prosecuted for causing the demand, or for desecration, or even for receiving stolen property.

Lead casket, St Bartholomew the Great

The work of the body snatcher was to supply bodies for dissection in London’s teaching hospitals. Their surgeons had no access to the bodies of executed criminals, so they started paying for fresh bodies, and did not ask too many questions about how the body was obtained. The most famous anatomist and surgeon in England was John Hunter. He did ground-breaking work in venereal disease, gum disease and gun-shot wounds. 3000 items of his work are displayed in the Hunterian Museum, in the Royal College of Surgeons, behind Lincoln’s Inn Fields. All of his items are from purchased (ie snatched) bodies.

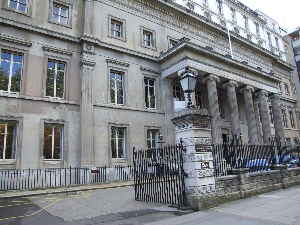

I found this topic difficult enough to research and write about so I have no intention of giving you some samples from the Hunterian Museum. Suffice it to say that you will find it in the Royal College of Surgeons in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. I have attached a photo of a 19th Century cauterisation instrument. I could have shown you artificial leeches, twelve-bladed bloodletting instruments and other 18th and 19th Century medical paraphernalia, but I have spared you.

19th Century cauterisation instrument, Hunterian Museum

Royal College of Surgeons, Lincoln’s Inn