In the 1871 census of England, Ann O’Loughlan, an Irish widow 70 years old, was living in a house in Willenhall, these days a medium-sized town, but of ancient Saxon origin, nestled between Wolfhampton and Walsall, in Staffordshire. It is embedded deeply in the Black Country culture and is (perhaps, sadly, was) most famous for its locksmithing and the humpbacked men who stooped heavily in the pursuit of making them. The Yale factory was here, too. That, and the Rushbrook Farthing, a local token that could be exchanged for goods or food and was peculiar to the district. The men here were iron workers, too, tough and grizzled from working in blazing heat amid showers of sparks and wary of huge troughs of red-glowing 1000-degree iron that they towed by hand, with no protective clothing. Their best friends were the miners of iron ore and coal. Remember this, because The Black Country (which could just as easily have been called the Iron Country) made the man who is at the centre of this story.

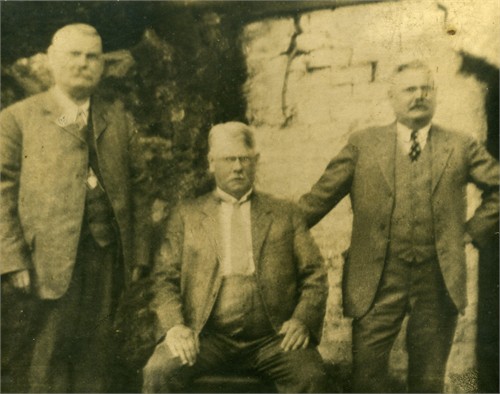

The date of the census of 1871 would have been early April. Living with Ann was her daughter Bridget Murry, 33 years old, also a widow and also from Ireland, but she had three children with her – Mary Murry, Richard and Matthew. Not long after the visit of the census enumerator, Bridget met a bricklayer’s labourer fresh from Ireland, called Patrick Tyrls. He was born in 1836 in Roscommon, and with her children needing a breadwinner, Bridget married him. I have not been able to trace Bridget’s first marriage – there were Murrys in the Wolverhampton registration district. As you can see in the photo below, the three boys were lifelong friends.

In the 1881 census, Patrick, 45 years old, was the head of a house at 27 Walsall St, Willenhall, plying his trade of bricklayers labourer. He spelt his name Tyrles and Bridget, now 43, still had Richard and Matthew Murry with her, at 16 and 14 years old respectively, who had become locksmiths – as had most of the men in this street. Mary Murry married a local miner, William Parker, in Willenhall and was living in 14 Clarks Lane, just 3.5 miles from her mother and brothers. Patrick and Bridget’s children, Patrick, James and Bridget Tyrles, were duly noted as “Scholar”, even though Bridget was only 3 years old. Two 60-year old bricklayer’s labourers from Ireland were also living in the house, as lodgers. With the wages that men were paid in middle and late Victorian times, the woman of the house often had to have lodgers in order to help her husband’s wages last the whole week.

Mary Murry

In the 1891 census, we find out that Bridget was from County Clare, in Ireland, and Patrick (or perhaps the enumerator) was spelling his name Tyrls. I am going to concentrate on the three Murry children for the moment, so we can account for them until at least 1911. They were not in this house for the census. Mary, who had married and moved out before the 1881 census, and was now Mrs Parker, was with her family in Bulwell, Nottinghamshire. Her marriage certificate tells us her father’s name was Thomas Murry and he was a brick maker. William Parker was a coal miner. This was a difficult and dangerous job. You will remember the Davy lamp that stopped miners from being killed from ammonia and coal dust; that invention, while saving lives, also made it possible for miners to work much deeper underground. If you could dig deeper, then you had to, and the hazards multiplied. William was still mining coal in the 1911 census. He called himself a “Coal Miner – Hewer”, which meant he was cutting material from the coal face, and he had done that for no less than 34 years. You have to admire his courage. Mary had added to her family – you will remember Thomas H Parker 1880, her firstborn, now she has Bridget 1884 born in Willenhall, along with William 1886 and Mary Parker 1890 both born in Bulwell.

In the 1901 census, Mary, at 42 years old, was a “Greengrocer shopkeeper – at home” by which I take it that she has some groceries for sale outside her house, or they are living above the shop. There is no sign of Thomas H Parker, but Bridget is called Bertha and she is a “Lace Mender” while younger brother William is a “Hawker (General)”, which would indicate he had a range of things in a suitcase and went door-to-door selling them. He was self-employed. Bridget was one of the 40,000 (mostly women) employed in the Nottingham lace industry, and she did literally mend lace. However, Mary’s family had grown some more: Charles 1893, James 1895, Winifred 1896 and George 1900 were all added to the family during the previous ten years in Bulwell.

The 1911 census is the last time we see the family, and they are still in Bulwell. As I noted above, William and Mary have been married for 34 years, and William has been underground at the coal face for at least that long. Mary 1890, the lace mender, has a daughter, Marjory Parker, who was just one month old on the day. Later, she was brought up by her grandparents, and adopted the name Marjory Selby Parker, after her father, Harold Selby, who never did marry her mother. Charles Parker 1893 (whom they call Chris) followed his father underground, because he, too became a coal miner, hewer. On the day of the census James 1895 was classified as unemployed, Winifred (Winnie, of course) had also joined the ranks of the lace menders and George 1900, the youngest, was at school.

To round off Mary Murry’s story, I am told the family of William and Mary Parker, lock stock and barrel, in 1916, climbed aboard a ship bound for Canada and moved to Paris, Ontario, where they all still live. So far I have only seen William on the Laurentic in 1914 and William with James in 1916 on the Corsican, bound for Canada. I shall keep looking. Marjory Selby Parker married in Paris, Ontario, and her family is in touch with me.

Bridget was 52 and the two boys, Patrick and James, were 18 years and 16 respectively. Patrick was called a “file cutter”, and he was the one who cut the grooves in files and rasps, whilst younger brother James was a brass finisher. If you have sat and polished brass with Brasso, you will have noticed the powerful odour. That comes from ammonia. It was a hazardous substance in late Victorian times too, but if you had a job as a brass finisher – polishing and perfecting items made in brass – you had to breathe it all day long; and men would often die young, of horrible lung diseases. A closer look at the next page of the census reveals that this house is in Court 8, Walsall St which is a cul-de-sac of about five houses, this house must be considerably bigger than No. 27 Walsall St. There are no less than six other men in the house, all “Boarders” and then there is Bridget Mildoon, 80 years old, who is a “retired lodging-house keeper.” It would appear that Bridget Tyrls has taken over the running of a lodging house, and she and her family have moved into it. The men, ranging in age from 17 to 73 years are all single, and except for the bricklayer from Birmingham, they are all from Staffordshire; one is a locksmith, three are bricklayers’ labourers, one is a retired carter and one is a salesman.

I do not think that it is too much of a stretch to say that Bridget, Patrick and their family have gone up in the world. It is very difficult to say who might have been the lead on this promotion, but I have written about some very brave and forthright Victorian women on this site, and it would not surprise me to know that Bridget was the driving force.

In the 1901 census, Bridget was 63 and a widow, but she was still living in Court 8, which, it transpires, was two houses from St Giles Church. Her daughter Bridget was 23 years old and married to Samuel Tomlinson, 29, with a son Thomas, just 2 years old. Since the rest of the family had left, there were two more boarders: eight of them all told. They ranged in age from 20 to 55 and all of them were locals, so they were engaged in the diverse skills young men developed in Victorian Willenhall.