MERRY CHRISTMAS 2018 FROM EWART AND ELAINE

Merry Christmas to you all from mostly sunny New Zealand

Yes, you did read correctly; after 19 years living and working in the UK, we have made a few changes…

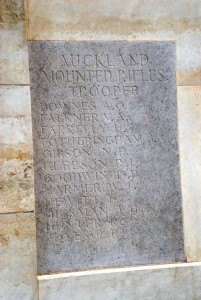

Following a delightful Christmas party with Iris at her care home in mid December, an early & happy snowy Christmas with our lovely Adams cousins and a delicious lunch with the Stredwick family on Christmas Day, we received a call informing us that Iris had fallen at the home and been taken to Watford Hospital on Boxing Day. For the next 7 weeks we supported Iris, Jill and Nick as best we could, including after her move to a care home in Norfolk, but the fall was to prove too much for Iris and she passed away a few days after her birthday in February. She had fought a long & valiant campaign against vascular dementia. Iris’s passing, for us, meant the closing of a very valued chapter of our lives with that generation of our Tearle/Adams family in the UK. It was Iris and Ivor who started it with us and neither of them was there anymore, along with many others. We began to think… It also made us consider our own future; fueling a desire to be back in NZ with our family. The next generation in the UK will continue to be a very important part of our lives from wherever we are and will hopefully visit us in our NZ home, along with our UK friends.

The year that followed has included:

- Having wonderful outings with Abby and Dan in Tearle places, St Albans and in London. It was so good having them live so close to us for a while!

- Going to wonderful concerts in London and out to dinners with the Stredwicks, also baby cuddles!

* Helping various people in the Larches with issues that needed sorting out in their flats (Elaine is a director)

- A trip to Switzerland: Basel, Bern, Zurich, Lucern, Interlaken and wonderful train journeys and boat trips in between.

- Trips around the UK to friends and family.

- Anh & Tien visited us in St Albans – we were so excited to have them there.

- Meeting several new Tearle families through our website & having lovely days out with them to places of interest in Tearle Valley in Bedfordshire, some sites in Buckinghamshire & in London.

- Ewart retiring from InTermIt and work in May, after 9 long years of faithful service in many schools in Hertfordshire. This resulted in some great parties to attend & some lovely gifts & hugs; hopefully some visitors to NZ in the future also.

- Elaine having a lovely luncheon send off from her teaching friends at Sandridge School and both of us having an evening celebration with this group and their husbands at our local pub in St Albans – Blackberry Jack, also a luncheon with Headline, her agency employers.

- Putting the UK flat on the market. Sadly, as a result of Brexit political games, the market stalled, and we were not able to sell. We engaged an agent, let the flat, packed and packed & packed until we could pack no more … bought our tickets and arranged to emigrate; with all that entails! Following the Brexit announcement by the UK government suddenly we saw many of our special friends feeling very unsettled in their new adoptive country; us too. In the weeks leading up to our own move we were helping others with theirs. We had not expected to be doing that.

- 16 May: our friend Ann collected us, drove us to Heathrow Airport and bade us a fond farewell. We flew out early the following morning heading to Singapore and a well earned break from packing, endless phone calls to organise and re-organise things for our new journey. We had little energy in Singapore but enjoyed walking in the warm sun after a long, cold, and at times snowy winter, knowing we would be heading into a second winter once we had touched down in Auckland. At the time having a summer that was just one week long seemed a little sad to us. We were, however, pretty lucky as it turned out, the NZ winter seemed to us to be rather mild this year. By October we were already in summer clothes & increasingly working long hours outside!

- 24 May: arrived in NZ. Stayed the next couple of weeks with our daughter and her family in Auckland. It was quite special walking to and from school with her son and catching up on his life. Going on photography visits around Auckland – shooting trees, sunsets, beaches and bridges was an eye-opener at just how far her photography skills and interests had developed in the 19 years we had been in England.

- There was a shock, though – how much supermarkets had changed while we were away – ESPECIALLY THEIR PRICES! We also attended our grand-son’s sporting events, mostly football (the Kiwis call it soccer) and an indoor evening football game called Footsall. We also attended numerous all-day soccer tournaments and we found out that our grandson’s team was very good, and very successful. We were introduced to delicious Auckland eateries and the Saturday markets. We bought a Suzuki Vitara, which doubles up nicely as a car and as a wagon, and for the first time, drove down to the farm to visit our house – oh no, the whole house lot of carpet was wet & very smelly! We had no chance to move in for several weeks while we visited daily to light the fire and to air the house. We bought appliances, sorted out insurance, phones, driving licences, bank cards, and Ewart having to attend a medical (cost: $61) in order to get back his heavy truck licence. The biggest challenge of all was getting our NZ pension and dispensing with our UK pension. There is an interim payment system working at the moment, but the matter is far from sorted. No fault with the Kiwis, though. We needed help with all of this because the Kiwis do it differently from the English. We expected that, and we are very grateful to the numerous friends who helped us to get through the paper war.

- Moved in with with Elaine’s mum in Hamilton. She was wonderful. We traveled to the farm every day and returned to her each evening, where she had especially prepared a lovely hot dinner for us, taking care to provide the very best she could. We were so honoured as that takes a lot when you are nearly 90! The amazing thing was that the more she did the younger and happier she looked. We all really enjoyed our time together in those few weeks.

- Once the house was dry we moved our things out of Mum’s basement and into our house, hiring a truck and utilising Ewart’s newly awarded heavy truck licence.

- While we waited for the shipment from the UK, Ewart cut the trees along the drive and ensured that the requirements of the shipping company were met – 3m wide drive, 5m high clearance. The truck came and went without too much drama, and left our 113 boxes of stuff in the family room, the lounge and the biggest bedroom. We still had almost no furniture, so we purchased three 2-seater loungers for the living room. Very nice. During this time Ewart spent many, hours outside, taming the lawns and re-establishing our much needed water supply, which also included 2 full days with hired diggers and electricians.

- He has also repaired the electric fences throughout the farm, digging in somewhere around twenty new fence posts and adding eight new gates. After seeing what happened as we arrived, when the fences were working so poorly that the cows had the run of our lawn and all the gardens, it is a relief to see they now stay exactly where they are put, and their water troughs are full of nice, clean water.

- An electrician installed new light fittings throughout the house and we bought new plumbing items that have yet to be installed. Once our life here becomes a little less hectic, we’ll have time to install them, promise. We also installed a whole house lot of curtains, and they have helped to dry out the house and carpet. I purchased a line trimmer, and was presented with a brush cutter – for my birthday! A new garden mulcher was next, and I have used these three tools most days since – the place looks a lot better but there is still so much to do. I planted a vege garden, which was soon producing for us. Lovely to have home-grown food again.

- We were not long moved into our house when we got the call that our nephew Kris had died in hospital. Though Kris had special needs he was a good artist, even having one of his paintings hanging in NZ prime minister’s office (John Key). It was a very well attended funeral & a great tribute to what Kris and his family had achieved in Kris’s 43 years of life, as well as plenty of humour. Kris was well known around Rotorua. It was also a great chance for the Tearle siblings and their cousins to get together after more than 20 years.

- Once we had moved in, Mum came down for a holiday with us for a week. We all had a great time together: lots of chatter & laughter, exploring family history on the internet, on the farm and in the house, cooking together and planning the model railway with Ewart. Mum loved the birds in our garden and they came to her when she whistled. We took her visiting friends and family, shopping, going to the beach at Raglan and we took her to meet her latest great-granddaughters Adele & Isla in Tauranga. She enjoyed being part of things when the diggers were here, the curtains were installed, the TV and internet connections were made. She really enjoyed seeing our new life unfold and meeting the people who made that happen. Mum loved to shop for gifts for others – it was her hobby – we went on a couple of shopping trips together and she found and bought for me a beautiful bowl which she gave me as an early birthday present. It now has pride of place on our formal dining room table. Every day was a special day and the three of us were very happy together. On her last day on the farm, Ewart said to her “You have been such a good girl, you can come again!”

- 23 May Mum turned 90 which we celebrated with a family pot luck dinner at her home as she wanted. Another great evening of laughter. Over the next couple of weeks Mum would continue to celebrate as her friends contacted her & sent gifts from Australia, other parts of NZ and Hamilton. Anh and a group of her friends came over and stayed for a week with Mum for her birthday & Mum loved it, going out with them as often as she could. The living room had many cards and gifts and Mum felt special. Her church also put on a special event in honour of her birthday, presenting her with 3 birthday cakes! Mum was very happy.

- Our grandson is just finishing his Yr5 at school and attended his first school camp a few weeks ago. He has been playing and attending coaching for football (soccer) around 5 times per week during the season, including playing Footsall. He also has regular play dates with a number of friends. His XBox has also become a valued part of his routine; he certainly thinks so. Reading and chocolate continue to be important too, as he devours his way through huge volumes of fantasy, history and intrigue.

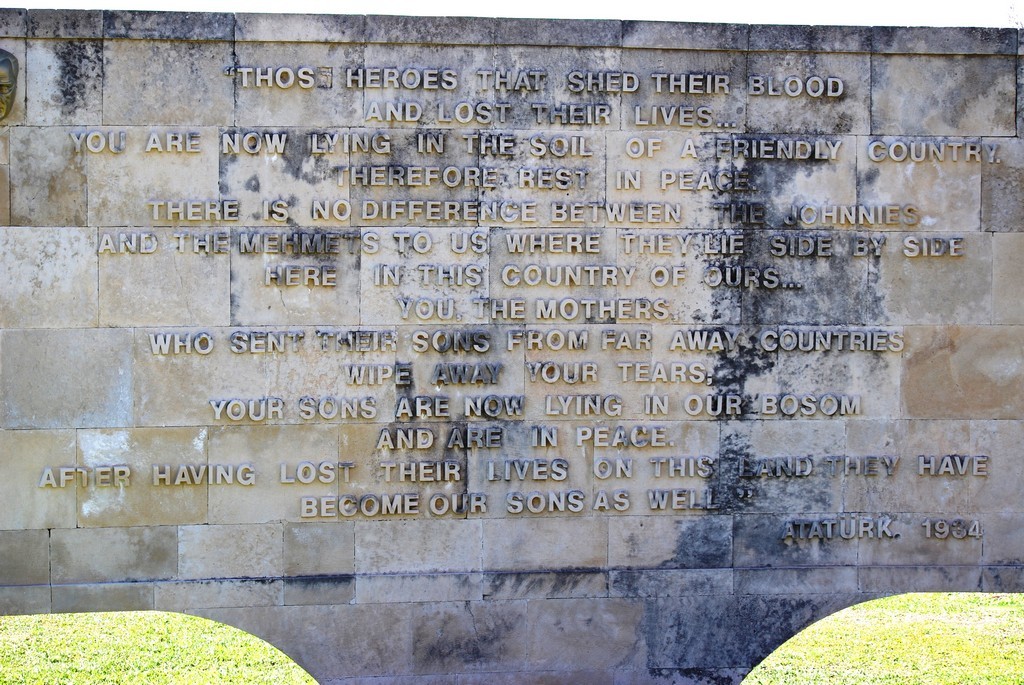

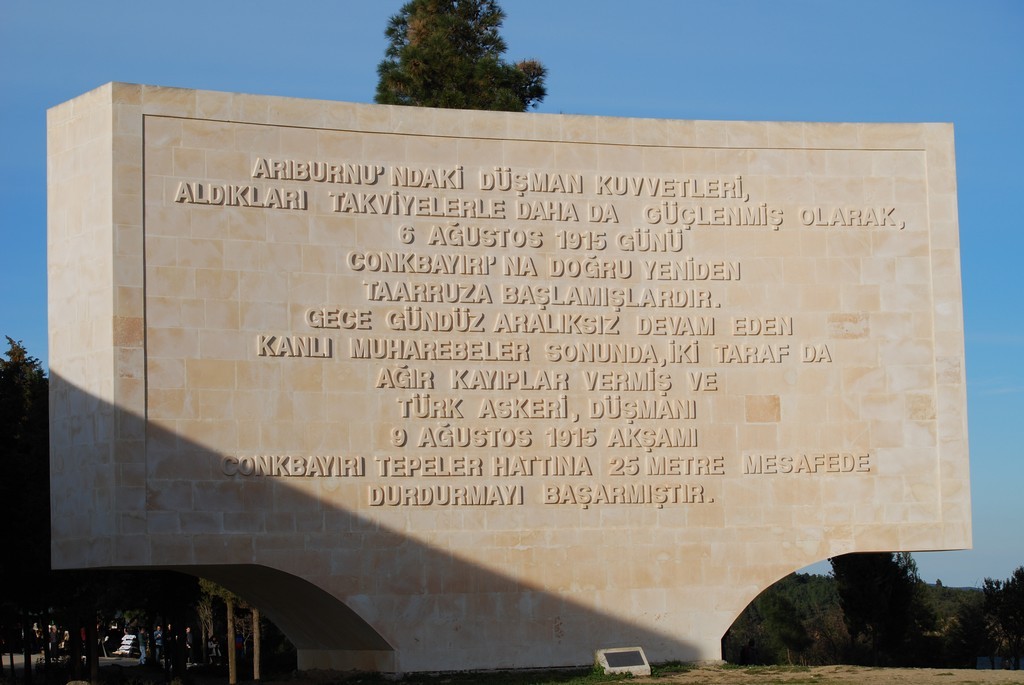

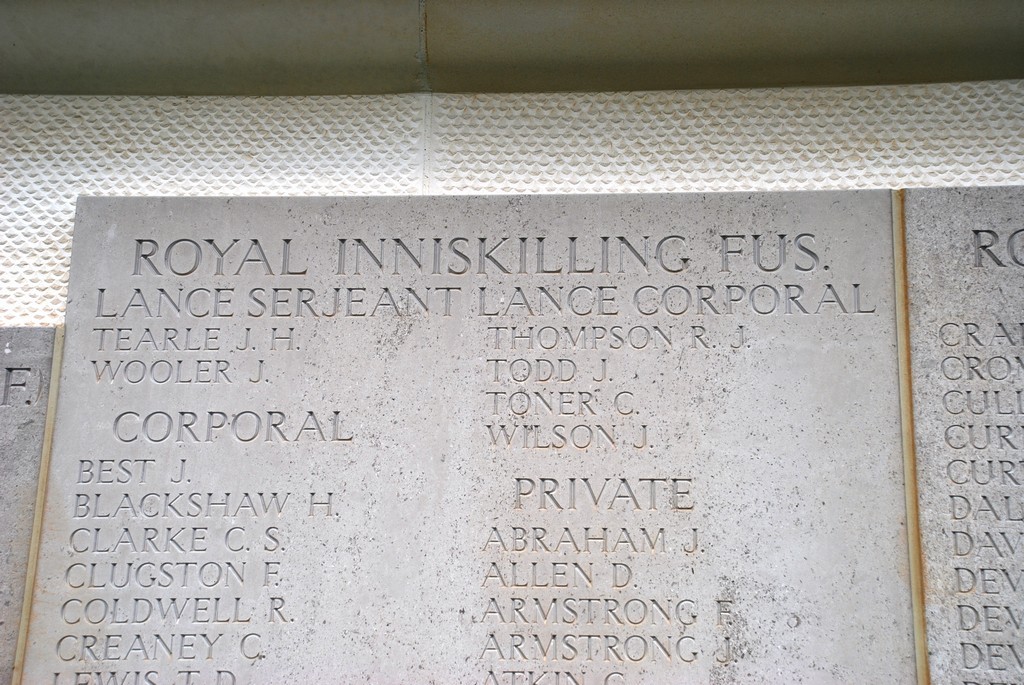

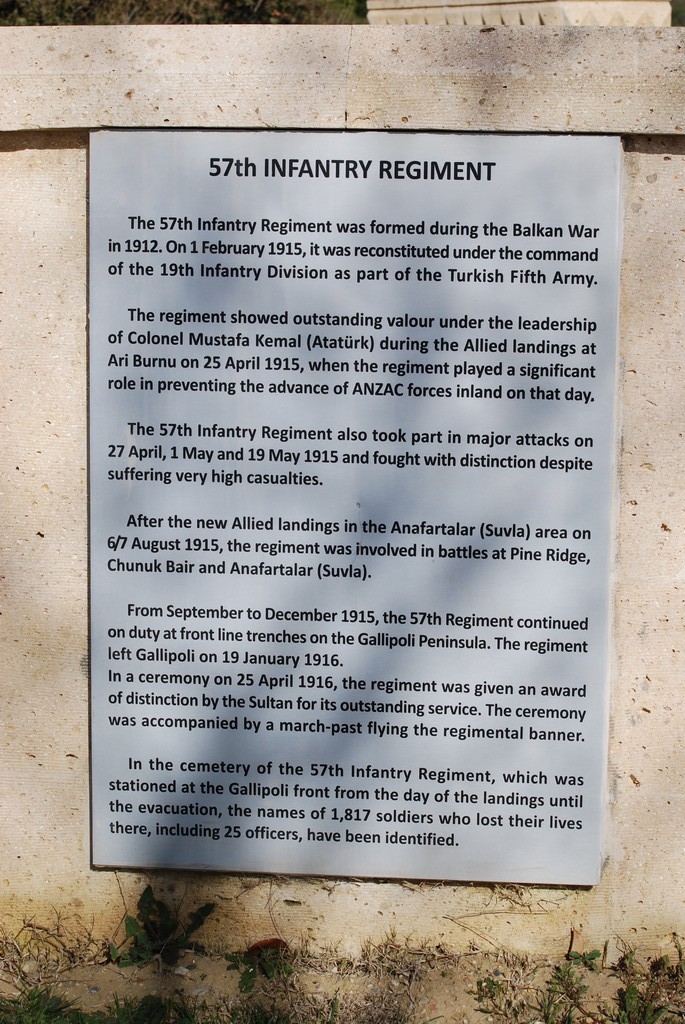

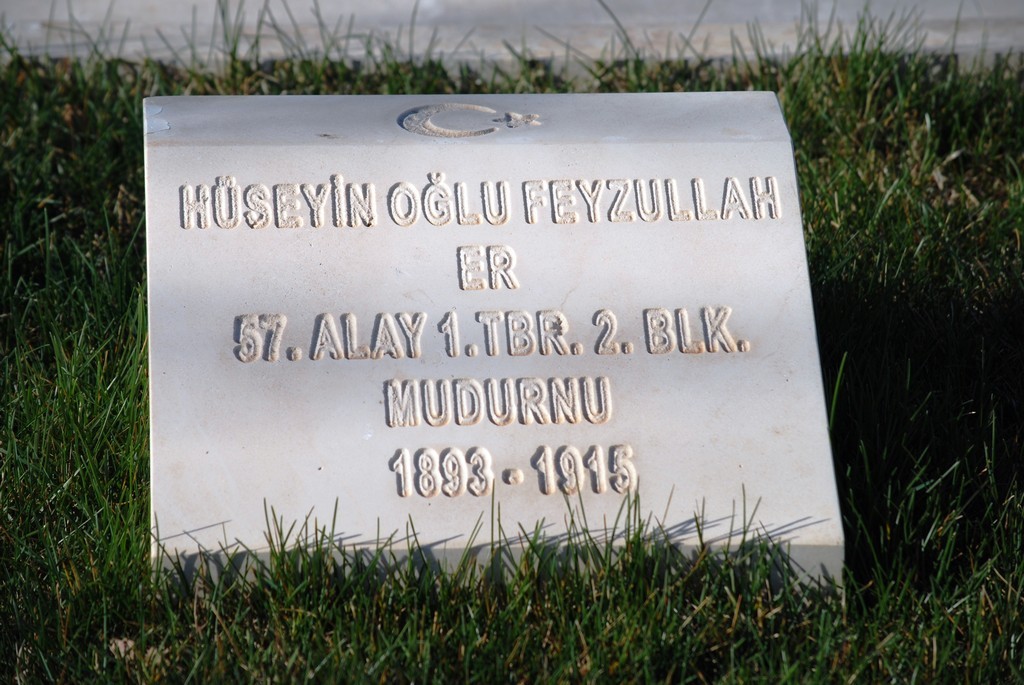

- We have had many lovely days and evenings out with special Kiwi friends and family since being home; dinners, coffees, meetings in town at new clubs, hot rod and vintage car displays, theatre, trips away to Auckland, Hamilton, Raglan, Te Waitere, Thames, Carterton, Masterton, Mauriceville, Danneyvirke, Tauranga, Taupo, Rotorua… We had planned to head down to Wellington to see the Ataturk memorial, then back via family in the Wairarapa but bad weather put paid to that. We hope now to do it as soon as we can get away once the weather improves, probably after Christmas.

- In the few days leading up to 28 Sept Mum started to feel breathless. On 27 Sept we received the diagnosis from the doctor that she was experiencing heart failure; on 28 Sept she died. Ewart and I stayed in Hamilton for the next three weeks as the necessary arrangements were made with family and others. Her funeral was held on 4 October. We had a great send off for Mum with family and friends coming a very long way to attend; Anh and Tri even made it over from Australia. We are very grateful. Tri sent over a charming film clip he had made of Mum playing the accordion, which we were delighted to show at the funeral, and we used a beautiful rendition of Time to Say Goodbye by Hope Russell-Winter (a former student of Elaine’s from the UK) which we downloaded from YouTube. Hope was delighted we were able to use her music in this way. Gordon was able to take a few extra days off work so he and Kathy, Ewart and I spent the next two weeks sorting out the house and grounds for Mum. Gordon also took me to Auckland in his Porsche to meet with our brother and family to do some family business. It was a lovely day for all concerned. Although we are now back at home some of these things are still ongoing for us all. Our friends & family have been really wonderful to us during this busy time; all hugs, emails and phone calls have been greatly appreciated.

- 27 October – Paul & Colleen lent us their batch (beachside cottage) at Raglan so we headed there for the weekend – and a good dollop of photography, eating out, football on the beach, walks alongside the estuary and shopping in the village. Gordon’s best friend also had his life support turned off that day after having a heart attack earlier in the week. It was mixed weekend of news, but much was enjoyable just the same. My grandson absolutely whipped me at Monopoly!

- 1 Nov – Ewart’s nephew from Carterton (now Waikato University) came to live with us and will stay until university goes back in about mid February. Taking him out has been a great excuse to see new things and to attend local events. He now has a holiday job in a local motel, so that will help him with his budgeting for next year at university.

- We have enjoyed being back sharing life with our god daughter Melody. While away she found a lovely new partner, Mark, & they have 3 beautiful children together, plus Mark’s extended family who are welcoming us to family events also. So far we have been to christenings and birthday parties. Great country functions! Wonderful hospitality.

- Hamilton Boys High School invited us to their senior prize giving so we could see Jason’s memorial trophy given to this year’s recipient. It was the most wonderful event and a very moving tribute to Jason was paid during the Headmaster’s speech. We were given prized seats centre front in the hall & tribute was paid to us both during the ceremony. An incredible Haka was performed for the Head Boy and the music performed by the quartet, bagpipe and the Pacifika groups were outstanding. It was the best-run school event I have ever attended. Afterwards, we were invited to the staff room to have morning tea with the staff, prize recipients and their families. We were introduced to the last 3 years of winners of Jason’s trophy. What wonderful young men they all were, their families too; the best of the best – it was humbling to see how excited they were to meet us. We are so pleased we went. It was a special day that will remain in our hearts forever.

So, in the lead up to another Christmas, here we are in a beautiful country location with incredible views of foggy winter mornings

and spectacular sunsets.

We are back in our beautiful Lockwood house, with a farm, rooms, housework, gardens and plenty of outdoor work to do on our thirteen acres. Ewart is now often seen with a chainsaw, or a wheelbarrow full of fencing bits, or a 2kg axe for chopping wood. Sometimes he is dragging timber, lighting and tending fires or, best of all, cutting the lawns using our ride on lawnmower – called Moa. For those who have mostly known us in the UK you will find that hard to imagine after seeing us live in one room! For NZers you will be wondering how we ever fitted into that one room, especially when you see what we brought home!

Merry Christmas everyone. We look forward to seeing visitors from all over the globe, and hopefully, perhaps, a little for travel for ourselves in 2019. We have plenty of catching up to do.

Lots of love from

Elaine & Ewart