Introduction

John Tearle was a Lt Commander in the Royal Navy during the Second World War. He was awarded the Atlantic Star and the Africa Star. He had served on the DEVONSHIRE and the MANCHESTER.

He was awarded five medals in all, which he wore on a bar during formal military occasions. One was the War Medal 1939-1945 awarded to all personnel who had completed at least 28 days service between 3 Sep 1939 and 2 Sep 1945; then the 1939-1945 Star which was awarded for operational service between 3 Sep 1939 and 2 Sep 1945, and John certainly had plenty of that. Another was the Africa Star, the fourth was the Atlantic Star, and the fifth was the Defence Medal. Servicemen were only allowed five medals for fighting in World War 2, and John had a full house.

He would have won the Africa Star because he had served on the HMS Manchester in the Mediterranean, and the Atlantic Star because the Manchester had also served in the Atlantic convoys, joined the search for the Bismark, and she had also been engaged in the reinforcement of Spitzbergen. She had a very sad end when she was hit by a torpedo dropped from an enemy aeroplane on 13 August 1942, and was severely damaged off the coast of Tunisia. Her captain decided she was unable to make it back to port, so to save his men, he ordered the ship scuttled. He was court-marshalled, found guilty of negligence, and dismissed from service. It is likely that John’s children would be very grateful for the captain’s gesture.

It is not clear when John Tearle served on the HMS Devonshire because she was never sunk, and since she was built in 1926 and scrapped in 1954, he could have served on her at any time, and for any length of time. She is famous for rescuing the Norwegian royal family in 1940, for which they still supply a beautiful Norwegian fir every Christmas to stand, emblazoned with white lights, in Trafalgar Square. In a book by the author entitled William A J Tearle, Firefighter of Lostwithiel, there is recounted the story of Victor Tearle, who served on the Onslow, and escorted the Norwegian royal family back to Norway at the end of the war. The Devonshire was the flagship of that convoy. She also served in the Eastern Fleet in the Indian Ocean escorting ANZAC forces from Suez to Australia.

He had a brother and two sisters, known familiarly to the family as Uncle Frank, Aunt Kitty (married to Robert) and Aunt Betsy, married to Angus.

It was noted, also that John Tearle, engineer, had been recorded in shipping passenger lists to-ing and fro-ing from London to Bombay:

10 Mar 1950 from Sydney to Bombay on the Strathaird

16 August 1950 on the Strathmore (sister ship of the Strathaird)

23 May 1952 he arrives in Southampton from Durban on the Athlone Castle

30 May 1958 he arrives in Southampton from Bombay on the Carthage.

This is because he was the chief engineer at Singareni Coal Mines, not far from Hyderabad. His wife, Jean Tearle, had also made the trip to and from Bombay many times, often accompanied by one or more of her children, some of whom had been born in India.

It came to light that John Tearle’s father was John Herbert Tearle. He was a man well known in the records stowed in the Tearle Tree. Born in 1881 in Bisham, Berkshire, he married Mary Ward in Westminster City in 1900 and in the 1911 census he was an accountant. It is now possible to construct the family of which John Tearle was a member:

John’s family:

Parents: John Herbert Tearle and Mary nee Ward (married 1900, four children)

Violet Elizabeth 1901,

Francis John Enoch 1902,

Kathleen May 1910,

John Tearle 1916

It becomes immediately clear who the nick-names in the introduction belong to:

Uncle Frank was Francis John Enoch Tearle (even his obituary in The Times called him Frank)

Auntie Kitty was Kathleen May

Auntie Betsy was Violet Elizabeth.

The entire family must have lived a long time in the North, because John’s marriage to Jean Searle in 1941 was in the Northumberland registration district, although, without the marriage certificate, there is no way of telling where in that district the marriage took place. Once it was established that John Tearle 1916 in the Tearle Tree was John Tearle, Lt Commander RN above, this ancestry became clear:

John Tearle 1916 and Jean nee Searle

John Herbert Tearle 1881 and Mary nee Ward

Enoch Tearle 1841 and Elizabeth nee Jones

Abel Tearle 1810 and Martha nee Emmerton

William Tearle 1769 and Sarah nee Clarke

Joseph Tearle 1737 and Phoebe nee Capp

Thomas Tearle 1709 and Mary nee Sibley.

From the point of view of John’s grandchildren, they are looking at nine generations of their family’s history. It is now time to put some detail into the events that led to the construction of the family tree immediately above.

The trunk of John’s Tree

John Herbert Tearle has an army service record. It is an odd entry of just 3 pages, and on the first page (militia attestation) someone has scrawled diagonally across it in blue pencil: Purchased 6/12/96. At the top of the page, there is the number that John Herbert will live with for the rest of his life – 5610, his military serial number – and the unit he was joining – the 3rd Battalion Royal Berkshire Regiment. There are some interesting answers to the questions on the form:

Born: Aldershot, Hants. It is not clear why he said this, because his birth registration clearly states he was born in Bisham, Berkshire.

Living: Marlow, Buckinghamshire

Employer: Messrs Medmenham Pottery Co, Marlow, Buckinghamshire, for which company he was a clerk.

The second page tells us he was 5ft 8¼ in tall with scars on his left knee. A medical examination pronounced him fit for army service on 25 November 1896.

The third page (statement of service) is very short;

Length of service: 25.11.96 to 5.12.96. 11 days. Purchased.

This would suggest he had not liked the army and, since he was only 18, it is safe to assume his father had paid the fee. His father, it turns out, is a very interesting man indeed, with a biblical name that many of us would love to carry even today.

John Herbert’s family

Parents: Enoch Tearle and Elizabeth nee Jones (married 1869, seven children)

Jeffrey Jones T 1871,

Minnie 1874,

Emily 1876,

Martha Elizabeth 1877,

John Herbert 1881,

Katherine Mary 1885,

Samuel Hugh 1889

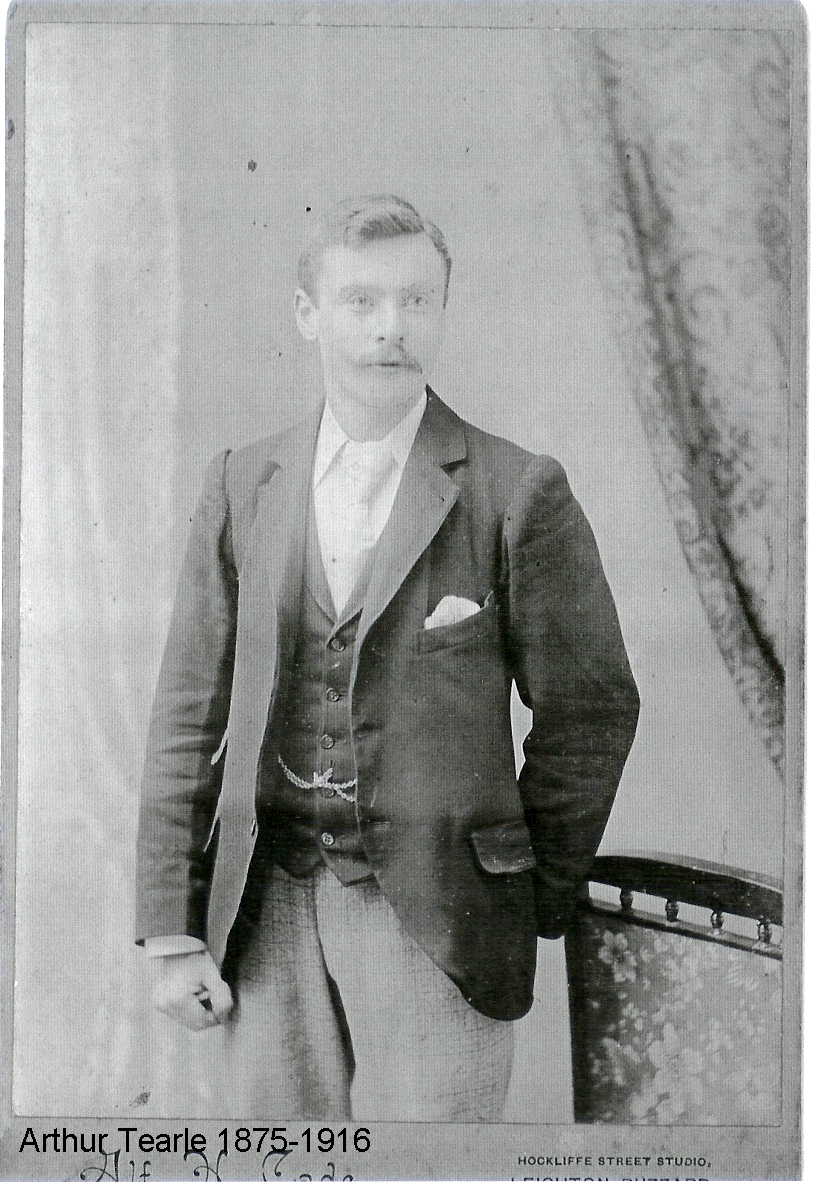

Enoch Tearle was born in Stanbridge, Bedfordshire, on 21 June 1841, the year of the ground-breaking census exercise that has taken a snapshot of British life every ten years since, with breaks in the war years. Abel, Amos, Enoch, Levi and Noah are some of the beautiful names liberally sprinkled amongst the Tearle families, matched by equally beautiful and historic names given to girls: Abigail, Ruth, Catherine, Charlotte, Martha and Phoebe to name just a few. The Victorians loved the Gothic as you can see from their churches and public buildings and even in the decorations on their more expensive houses. Gothic was part of the language of their belief in God, and so their children’s names reflected this spirit of their deep-seated Christian beliefs. What better way to express your devotion, than to give your children the names of His favourite sons and daughters?

From Bisham in Berkshire to Stanbridge in Bedfordshire we have, in one bound, leapt into the heartland of the Tearles. It is in this village, and in the little valley where Stanbridge nestles, that the Tearles have lived, worked, loved and died for at least five hundred years. The Tearles call it Tearle Valley, and the wider district is known as Tearle Country. The map of Stanbridge helps to delineate the boundaries: the village lies at the head of a valley aligned roughly north-west to south-east, with Stanbridge at the head. Even Eggington is not within Tearle Valley. There are limestone cliffs to the south-west. This limestone has been extracted for building blocks from time immemorial. It was called Totternhoe Stone and it was soft and carveable, but hardened nicely over time – perfect for lining the walls inside, for instance, St Albans Abbey, now St Albans Cathedral. Along the base of the upland runs the A4145 from Leighton Buzzard to Hemel Hempstead. On this road is Northall. An arch drawn from Northall across the north of Stanbridge to the A5 will describe the top of Tearle Valley. Following the A5 (Watling Street) to the junction of the Icknield Way – which, since ancient times, has followed the dry route along the tops of the hills through this part of Bedfordshire – will lead to the junction of the A4146, and everything inside is Tearle Valley, the ancestral home of most of the Tearles alive today. Inside the valley are Totternhoe, Eaton Bray and Edlesborough. Within ten miles are the country towns of Leighton Buzzard, Luton and Dunstable. These towns are in the wider area known as Tearle Country, and there are more Tearles in this small area of Bedfordshire than anywhere else in the world.

It turns out that the Tearles are a Bedfordshire, and indeed a Stanbridge family of rural folk who have worked the land as tenant farmers, and occasionally land owners, until the last Tearle who lived in Stanbridge died in a cottage on Peddars Lane in 1956.

And Enoch? He was the very model of a Victorian villager. His sister Ann was a strawplaiter who died young at just 47. She never left home and never married. His sister Sarah married a fellow villager, Ephraim Gates and went to Watford. Ephraim secured a job on the railways, but very sadly was killed walking along the line in the fog of an early Monday morning, in October 1872. It must have been desperately difficult for Sarah, a washerwoman, to care for her children after Ephraim’s death. His brother Amos moved to Walsall in Warwickshire, as a mining engineer. He married there and in the 1911 census he was a retired engine driver. His sister Phoebe was married in the beautiful little Stanbridge church in 1863 and also moved to Warwickshire where she registered the birth of three children in Nuneaton, only 20 miles away.. His sister Mary Clarke Tearle was baptised a Methodist in a tiny brick chapel next to what is now the Stanbridge school. The chapel no longer stands. Enoch’s youngest brother was Benjamin. He, too was baptised a Methodist. He was in the Royal Artillery (Southern) discharged on 15 February 1883. His regimental number was 23882, he was a gunner (ie a private) discharged at the end of his 1st period of service. He had accumulated no service towards his pension. This would appear to mean that either he was on a limited engagement, or that he had not served abroad. In the 1891 Stanbridge census, he was an agricultural labourer living with Alfred and Annie Buckingham. He died in 1900, never married.

When you look at these little vignettes of Enoch’s family from 1841 to 1900, it is possible to see the impact of waves of change that transformed the Victorian years. The eldest girl shows the farm-based life of the Bedfordshire village. Strawplaiting was not well paid and a plaiter had to make a length of about 6 yards a day. From time to time a plait dealer would sell the families bails of straw and then collect the plaited lengths and pay the family for them, by the 6-yard length. There is an excellent little display on this craft in the St Albans Museum near the centre of the city, and a very extensive and fascinating display of the strawplaiter’s art in the Wardtown Museum in Luton. It is an enlightening experience to see both the complexity of the task, and the simplicity of the cottage that housed it. The lengths of plait would be turned into straw hats, and whilst Bedfordshire is no longer the hat-making capital of the world, Luton even today has businesses that make the very best hats for people who are about to attend the most prestigious events, such as the horseracing at Royal Ascot. Children as young as five were working at plaitmaking – as long as their fingers could perform the motions, they were at work. It sounds terrible, and it probably was, but to the girls concerned, it gave them a freedom that few other women in England enjoyed – because they had their own money. This means that they could stay out of service. It meant they did not have to find a poorly-paid, and sometimes very difficult job, in someone else’s house performing menial tasks for long hours, and being constantly at the call of anyone their senior. Not having to be in service was an ambition very few people in Britain could hope to attain. In this respect, the Bedfordshire girls were lucky.

Over the one hundred years from 1841 to 1941, life in Britain changed beyond recognition, and Enoch and his family felt the full force of those irresistible changes. The major element of change for the Tearles was education. Methodism introduced free education for country children that had never been available before, and literacy allowed poor families such as the Tearles to take advantage of the other huge change that occurred in the 1840s – the railways. In about 1838 a line was laid from Leighton Buzzard to Euston Station via Dunstable – and suddenly London was only forty miles away; you could save up a fare and take a third class carriage all the way to London, and be there in a day. Elsewhere in tearle.org.uk I have discussed the Willesden Cell, a group of villagers living in London who traveled to and from Stanbridge. They lived in railway cottages and earned railway wages. Nothing could be further from the rural life than that. Their education, no matter how basic, equipped them to work in urban occupations and the railways supplied the means to travel there, and even the occupations in which to work. And that life banished crop failures and starvation for those families forever.

In the midst of all this change, what did Enoch do? The best way to explore his life is through the censuses because without too much difficulty they can be download from ancestry.co.uk and the source documents can be examined. In 1841, his father Abel and mother Martha were living in a cottage in Stanbridge with Ann, Sarah and Amos, as well as his mother’s younger brother. Enoch’s father was an ag lab. This is a Victorian catch-all phrase for anyone, no matter how skilled, whose fundamental means of survival was working for a farmer. The census was usually around April, so Enoch does not appear here, but he is not far off.

Enoch’s family:

Parents: Abel Tearle and Martha nee Emmerton (married 1833, eight children)

Ann 1835,

Sarah 1837,

Amos 1839,

Enoch 1841,

Phoebe 1843,

Mary Clarke T 1846,

Benjamin 1848,

Elizabeth 1851.

In 1851, there is a picture of unchanging, stable rural life, as glimpsed through the kitchen window. Martha is an ag lab wife, Ann and Sarah are strawplaiters, Amos (11yrs) and Enoch (9yrs) are scholars (they are at school) and Phoebe, Mary, Benjamin and Elizabeth probably have the run of the village green. It is almost certain that Amos and Enoch were educated at a school in Stanbridge because in 1842 the Primitive Methodist congregation bought a thirty foot plot of land for £5 and built a chapel and school. It was a fervent belief of the Methodists that the individual needed to read the Bible. They had to know for themselves what the scriptures said, so they could fully understand God’s Word. In many English villages, if there is a Methodist chapel, it would have doubled for a couple of classrooms and it would have preceded a state-run school by several decades.

In 1861, Abel was a platelayer on the railway. No longer a mere ag lab, Abel was employed in permanent work. Platelayers, as the name suggests, built the railway track. For all that, it can’t have paid a huge amount of money because Martha, Ann, Phoebe and Mary were all still plaitmaking, while Benjamin and Elizabeth were attending to their studies at school. However, Enoch and Amos are not there in Stanbridge.

Enoch married in 1869. Actually, he married twice; there is a certificate for their marriage in St Paul’s Liverpool, the details of which are:

17th November 1869 at Saint Paul’s Church, Parish of Liverpool, Lancaster.

Enoch Tearle: Full Age: Bachelor:

Father’s name Abel Tearle: Profession: Platelayer

Elizabeth Jones: Full age: Spinster

Father Samuel Jones Profession: Farmer

After banns

Witnesses Mary Drury and George Foster

And then he married again in a Methodist chapel, in Wales:

8th September, 1870 at the Wesleyan Chapel, Johns Street, Chester, Flintshire

Enoch Tearle: Aged 28 years: Bachelor:

Profession: Private 4th King’s own Regiment: Residence: Chester Castle.

Father: Abel Tearle:

Elizabeth Jones Aged 21 Spinster:

Residence Shields Court, Castle Street, Chester.

Father Samuel Jones: Profession: Farmer

By certificate:

Witnesses: Richard Sanders and Esther Taylor

It would probably not be a surprise, given her name, that Enoch’s wife, Elizabeth Jones, was Welsh, and since the distance from Liverpool to Chester is not very far, perhaps Enoch and Elizabeth went to the nearest place in Wales from Liverpool while he was on furlough. Elizabeth came from Hope’s Place, Flintshire, which is a village not far from Wrexham. I wonder whose idea it was to have a second marriage ceremony in a Methodist chapel in Wales? It is a charming and romantic gesture. I am fairly certain that the St Pauls in question was the beautiful, classically Georgian building in central Liverpool demolished in 1931, almost inevitably, by the railways, and now the site of the Liverpool Football Club’s Anfield Stadium.

From the second marriage document it is clear to see what Enoch has been doing in the previous few years – he joined the army. And he has set a precedent. He has joined the King’s Own Regiment. Its full name is the King’s Own Royal Lancashire Regiment, usually shortened to the Royal Lancs Regt, or The King’s Own. The 4th Division (also known as the 4th Foot) has a home in Aldershot, Hampshire.

In 1871, the census people came to visit Enoch, and there is a lot more about his activities. For some reason he was counted twice, and that is most unusual. The first record has Enoch in the Chester Castle Barracks, he is a private in the 4th Foot, and he is from Leighton Buzzard, Bedfordshire. Amongst the soldiers is a drummer from London and other men of the 4th Foot come from Liverpool, Chester, Ireland, Wareham, Northampton and Cambridge. The second 1871 census return is from Bridge St, Chester, where Enoch Tearle, aged 29 lived with Elizabeth Tearle, aged 20. Enoch described himself as private, soldier, 4th King’s Own Regiment, from Stanbridge, Bedfordshire, while Elizabeth was simply dressmaker, from Flintshire. This is not a military street, even though Chester has been a military town since Roman times. Chester Castle itself was built by the Normans and still stands within the city walls. In this street, there are another two dressmakers, a master painter, a stone mason, a butcher, a cashier in a millinery department, a draper’s assistant and a general servant. There is even a pupil teacher, the backbone of the profession in the early history of education in England. All of these are working people, but this neighbourhood is a long way, in kind and in distance, from Enoch’s village. There are no farmers and there are no ag labs. And, interestingly, in this street there are very few children.

In 1881, Enoch is much closer to his roots than in bustling, urban, militarised Chester, but the census return still tells a well-traveled tale. Enoch and Elizabeth are living in the village of Bisham, Berkshire, where he is a butler, and Elizabeth is a full-time wife. He says he is only 34 and she is 29. Enoch’s arithmetic is a little out of sync with his age because, since he was born in 1841, he was 40 in 1881. Enoch has left the army and he is working, to make up the gap between his military pension and what he needs to spend to keep his family in the manner he wants. The most senior person in a great house is the cook; the next most senior is the butler; Enoch would be on a good wage. He also has a family: Jeffrey Jones Tearle, Minnie, Emily and Martha Elizabeth. Jeffrey was born in Aldershot, Hampshire, the southern military training camp; Minnie was born in Woolwich, the London barracks; Emily was born in Athlone, Ireland and Martha was born in Aldershot. John Herbert was born in 1881 in Bisham, Berks, so he is not far away when the census enumerator comes knocking. That Emily was born in Ireland means that Enoch did his country’s duty in policing the Irish revolution that began in 1798 and finally ended with Irish independence in 1922.

The 1891 census shows Elizabeth living in Great Marlow, Buckinghamshire. Neither Elizabeth nor Minnie, the eldest girl, give an occupation but Emily is a dressmaker and Bessie, John Herbert and Katherine Mary are at school while little Samuel Hugh is just two years old. The range of occupations is expanding in small town life – there is a foreman in a brewery, a locomotive fireman, two millers and a butler in Elizabeth’s street. Enoch was in London for this census, working at 24 Portland Place, not far from the present Broadcasting House and today houses the Associated Board of the Royal School of Music. In 1891 this imposing building was the home of three elderly Yorkshire sisters, all single. They had a household of no less than nine staff, and Enoch was their butler.

In 1901, things have changed a little. Enoch’s occupation as the enumerator wrote it is illegible because of a deep black cross over it, drawn by the person who was checking all the different occupations people gave and distilling them into a few codes. So, for instance, ag lab was still in use for a farm worker. Enoch was definitely a worker so he was employed, rather than running his own business. Elizabeth, Katherine and Samuel Hugh do not give an occupation, and at 11yrs old it is certain that Samuel is still at school, but at 15yrs, it is not clear whether Katherine might be still at school, although it cannot be ruled out. The situation, though, looks calm and peaceful. Marlow, Buckinghamshire, is a rural idyll on the banks of the River Thames with large English trees, an imposing spire on a tall and elegant church and a graceful weir down which the Thames tumbles and chortles on its way to London. Enoch has moved back to his comfortable place in rural England.

The 1911 census always gives a little more than one would expect from a dry catalogue such as a census. For instance, it notes that Enoch and Elizabeth have been married for 41 years and had a total of nine live births, of whom seven are still living. Enoch is nearly seventy years old, and says he was formerly Army. Katherine is a teacher (assistant), employed by the Buckinghamshire County Council. Enoch says they are living at home in Jubilee Cottage, Newtown, Marlow.

Having found out as much as possible from the censuses taken in Enoch’s lifetime, there are a few details that can be filled in on Enoch’s army record because his discharge papers from the army in 1879 are in the public record. Firstly, they tell us he enlisted at Bedford on 15 November 1858 into the 2nd Battalion, 4th Division, King’s Own Royal Lancashire Regiment, when he was just 18yrs old and worked as a farm labourer. He was 5ft 4in tall, had sandy hair and a slight frame. He had been in service for 21 years and 9 days, which consisted of a first period of 9yrs 145 days then re-enlistment for a further 11yrs 214 days. In that time he had collected a silver medal for long service and good conduct, plus 5 good conduct badges. He was rated as conduct very good, 5B, which would appear to be the best conduct of all, since conduct ratings ranged from fair, then good 1B to 5B, then very good 1B all the way to 5B. In a written note, his conduct is described as very good, habits regular, temperate. The Methodists were keen on temperance, so Enoch was following his up-bringing. His medical record says he was sick four times in Corfu, twice being treated for climate-related conditions, between 1858 and 1863, otherwise he was never injured and never wounded. That is why he was missing in the 1861 census – he was on the island of Corfu, off the coast of Greece. He was actually on service abroad for 9yrs. Also formally noted was that he had never been entered in the regimental defaulters book and he had never been tried by court martial. His formal discharge date was 25 November 1879, he was 39yrs old, of sallow complexion, brown eyes, red hair and his occupation was labourer. His intended place of residence was Captain Yorkes, Bisham Grange, Gt Marlow, Buckinghamshire.

At this point two more documents concerning Enoch came to light. One was a listing in the Kelly’s Trades Directory for 1907 which shows Enoch was a shopkeeper in Newtown, Marlow. Presumably, he was trading from this cottage, or at least from a premise very close to it. The last document is the calendar listing for the probate on Enoch’s will. His date of death was 4 March 1920 and the administrator for the £161 worth of his estate, was Bessie Tearle, spinster. “Bessie” was Martha Elizabeth Tearle, born 1877 in Aldershot. Bessie died, still unmarried, in 1957, in Hastings, on the south coast.

The reason for spending so long telling Enoch’s story is because it has ripples and resonance for many of his descendants; to John and even to John’s children. Enoch must have been a larger-than-life, formidable character of a man, because his influence on the future of his family is far-reaching and plain to see. However, for the moment, the story is focussed on where the roots of John Tearle’s Tree are firmly planted.

Abel’s family

Parents: William Tearle and Sarah nee Clarke (married 1795, eight children)

Joseph 1796,

Joseph 1797,

John 1799,

James 1801,

Benjamin 1804,

Daniel 1806,

Mary 1808,

Abel 1810

There is already mention of Enoch’s parents, Abel Tearle and Martha, but a closer examination is rewarding. Abel was born in Stanbridge in 1810; he is one of a family whose christenings were recorded in the Stanbridge Parish Records (PRs) that were reported on earlier. Abel is almost at the end of the records that Emmison transcribed:

Abel son of William and Sarah Tearle was baptised on 15 April 1810

Held under lock and key and hidden in the grand old Victorian safe deep in the vestry, is the Stanbridge Church banns register. When I first visited Stanbridge Church in 1997, the churchwarden carefully lifted it from a shelf in the safe and, walking amongst the pews, finally stopped and laid the book on the wooden lid of the medieval font. He opened the blue cover and I saw that the first page was headed 1821 and the first entry was dated fifth day of June. On that day, William Millar and Mary Janes had heard called out in the church the first of their three banns. The book has many pages of printed forms and the churchwarden explained that the vicar fills out one form for each couple who are going to be married. All the entries are written in india ink, which is very dense and contains no acid. The vicar uses the same kind of dip pen that children used in primary school in the 1950s, with an inkwell in the corner of a battered wooden desk, with its flip-up seat and hinged lid. Asked why the book was not in a museum, or a historical collection, the churchwarden replied,

“Because we are still using it.”

Here is a book that opened in 1821 in a small church in a Bedfordshire village and it is still in use, recording banns for the villagers of Stanbridge who love each other and want to be married. In 2006, at the very first TearleMeet in Stanbridge Enid Horton, and her daughter Lorinda, made it their mission to transcribe all the Tearle events recorded in the register. There were thirty-one entries. The first was 9 September 1825 when John Tearle married Elizabeth Mead, and the last was 21 April 1923 when Ernest Webb married Mabel Edith Tearle. The record held thirty-one marriages in 98 years. Those names are a roll-call of the Tearle family in Stanbridge. On 23 June 1833 Abel Tearle had the first of the three readings of the banns announced for his marriage to Martha Emorton (sic). The vicar has carefully overwritten the e he wrote in Emerton with an o. After much research and checking with modern spellings it was noted that the most common spelling of the name was Emmerton, so that is how it will look from this point forward.

Abel and Martha were married in the little Tilsworth church a few hundred yards along the road from Stanbridge, on 9 July 1833, because at this time, marriages were not held in Stanbridge. It is notable that no-one in this ceremony could write, except the vicar. Abel, Martha, and the witnesses William Crawley and Eliza Emmerton all make their mark. We see nothing more of Abel until the 1841 census. Abel and Martha are living on the Leighton Road. For someone standing on the grass where the cars park outside Stanbridge Church, looking straight up Mill Road to Eggington, Leighton Road is to the left and does indeed go to Leighton Buzzard, about six miles away. Totternhoe Road, as it was called then, goes off to the right. It is now called Tilsworth Road and runs past that village towards the A5. Upon examination of the Stanbridge pages of the 1841 census, it is clear that anyone who does not work on the land has an occupation: Rebecca Hines is a plat (sic) Ann Emmerton is a strawplaiter, Thomas Gregory is a farmer, George Crawley is a butcher, Charles Horne is also a farmer, Charles Bridger is a tailor, John Flint is a shoemaker and Mary Mead is a bonnet sewer. All the rest of the males are ag lab, and all the rest of the women have no occupation at all. In the 1841 census, it is best to remember that adult ages were rounded down to the nearest age divisible by 5, such that someone who was actually 37 years old was recorded as 35. Children’s ages were near enough to their correct age. Abel Tearle, ag lab, then, is thirty years old, Martha is 25 with her father, Joseph Emmerton who is 65 and still an ag lab – and there are the following children:

Ann, 5yrs

Sarah, 3yrs

Amos 2yrs

We shall skip the 1851 census, partly because Abel is not there, and partly because Enoch is, and we have already looked at his page, above. Martha is described as an ag lab wife.

In the 1861 census, things have changed a lot. Abel is a platelayer on the railway. It is likely that Abel missed the 1851 census because he was in a gang laying the plates for the railway somewhere between Preston, Leighton Buzzard and London.

In the 1871 census, Abel is 61 and still a railway plate layer, while Ann (25) and Elizabeth (20) are straw plaiters. There are only two ag labs on this page. Things have certainly changed, because James Birch is a railway lab, David Giltrow is a dealer (in plait) John Ellingham is a dealer, and Elizabeth Hinde is a dressmaker. It is interesting to speculate that there might be as many men on the railways as there are left on the land. The Industrial Revolution is well under way.

In the 1881 census there is a sad story; Abel is 71 years old and is an agricultural Labourer. He could not retire, he has to keep working. He has gone back to the only other work he knows apart from the railways, and that is the land. It is unlikely he is earning very much, because his daughter Ann is at home helping Martha. Although the enumerator has not given her an occupation, Ann’s straw plaiting would still be bringing in money that the whole house depended on. Abel died on 9 October 1882 and was buried on the 13th.

Stanbridge is an odd little church and parish, with a complicated political history. It was part of the Peculiar of Leighton Buzzard which meant it was not part of the Archdeaconry of Bedford, and its rector was a prebend of Lincoln Cathedral. In short, this meant that while baptisms and burials could be conducted in Stanbridge, marriages were performed in All Saints Church, Leighton Buzzard, or in the bride’s parish, hence the records of Tearles marrying in the Tilsworth church. A trip to Leighton Buzzard just to see its parish church is well worth the effort; the tower is so tall it can be seen for miles on the approach to town. The marriage of William Tearle and Sarah Clarke is noted in the Leighton Buzzard PRs:

William Tearle and Sarah Clarke were married on 12 November 1795

Very sadly, the Leighton Buzzard Parish records also record that Sarah Tearle died and was buried in the little cemetery that surrounds Stanbridge Church, in 1811, it seems not very long after the birth of her last child, Abel 1810, who was to become Enoch’s father.

The wife of William Tearle was buried on 11 October 1811

The Stanbridge census of 1841 reveals William Tearle (aged 70, so born around 1771) in Stanbridge, but he was married to a Judith who was 65 years at the time. The Stanbridge PRs tell who she was:

William Tearle and Judith Knight (of Tilsworth) were married on 9 November 1812

It seems heartless that Sarah died in Oct 1811, and William remarried in November the following year, but both William and Judith would have benefitted a great deal from this marriage – William would have had a wife to look after the children while he worked, and Judith would have had an income and a respectable home. We cannot criticise them. A close look at the 1841 census form indicates that William was an ag lab, so that is what he would have been all his life. It is not possible to know what sort of work he did, and almost all the men on this page of the Totternhoe Rd were ag lab, but there are some occupations listed: Thomas Buckingham was on parish support and Thomas Gadsden was a plait dealer while Sarah Bunker, Mary Turney and Sarah Corkett were all straw plaiters. You can see clearly how farming life completely dominated the village of Stanbridge until the railways arrived and people began to take advantage of them from the 1850s.

It is difficult to know any more about William than this; he probably did not own his cottage, and he probably had to move several times during his working life; possibly on the basis of different farmer, different cottage, and possibly also moving to a larger cottage to cater for a larger family. There is constant movement from one little cottage to another in and around Stanbridge, thrown sharply into focus every ten years. We cannot know what William did as an ag lab and we cannot know where he worked, or even if he had work on one or many farms. William died in 1846. We know a little about his parents. Here is William’s baptism in Stanbridge Church:

Ann the daughter of John and Martha Tearle was baptised on 5 February 1769

William the son of Joseph and Phoebe Tearle was baptised on 10 December 1769

These two baptisms in 1769 are for children (Ann, and William) of two separate families – John Tearle and Martha nee Archer, and Joseph Tearle and Phoebe nee Capp. The two men are brothers, and Joseph is the eldest son of his family. By checking for other Joseph-Phoebe births, it is possible to find the entire family. There is a very short note about each family that resulted:

William’s family

Parents: Joseph Tearle and Phoebe nee Capp (married 1765, twelve children)

Joseph 1766 married Mary Pointer, one child

Mary 1768 married Joseph Wright, 6 children

William 1769 (as noted above) married Sarah Clarke, 8 children

Phebe 1771 (sic) died 1771, Thomas 1771, died 1771

Thomas 1774 died 1776

Ann 1775 married James Sharp, 6 children

Richard 1778 married Mary Pestel, 8 children

Thomas 1780 married Sarah Gregory in Chalgrave (no children) then Mary (surname, and maiden surname, unknown) who already had two children in Luton, 3 children

Pheby 1782 (sic) no record beyond this

George 1785 married Elizabeth Willison, 6 children

John 1787 married Elizabeth Flint, 3 children. Died 1818

With a family such as this and so numerous in grandchildren, it is no wonder that Joseph’s branch is very influential amongst the Tearles. You can see clearly the children who have died because there is another with the same name, later. Joseph and Phoebe were determined to have a Thomas, named after Joseph’s father, and a Phoebe to ensure her name carried forward, too. In the case of the twins Phoebe and Thomas Tearle, there is a single burial record for them in 1771 but no baptism, so I am assuming that they died very soon after birth. There was another Thomas baptised 02 January 1774, for whom there is no burial record, but since there is a later Thomas (1780) there is, completely contrived, a death date of 1776. Thomas Tearle, baptised 1780, did survive and married Sarah Gregory in the beautiful little church of Chalgrave, across the A5 to the north-east of Stanbridge, in 1802. Just before leaving Joseph’s Tree, it is well to look at the memorial under the trees in Stanbridge Church to John Tearle (of this family, immediately above) born 1787, who died in 1818. His daughter, Hannah Tearle born 1816, married Henry Fleet, a fellow Methodist in the village, and the two of them went to Sierra Leone on a great Methodist mission and adventure. The two of them fell violently ill on the ship and died within weeks of each other, shortly after arriving in Africa. Their sacrifice for their faith and their idealism is memorialised on a tablet which hung on the wall of the Methodist chapel. It was rescued when the chapel was demolished and it is secured on the wall of Stanbridge Church itself.

We have now arrived at one of the roots of the Tearle Tree. Joseph Tearle and Phoebe are William’s parents, so John Tearle 1916, Lt Commander RN, descends from Joseph Tearle of Stanbridge.

Joseph’s family

Parents: Thomas Tearle and Mary nee Sibley (married 1730, eight children)

Mary 1731, Elizabeth 1734, Joseph 1737, Thomas 1737, John 1741, Jabez 1745, William 1749, Richard 1754

Although these boys, Joseph and Thomas, were baptised at the same time, they may not have been born at the same time. However, Joseph, because he was the eldest son, inherited a farm which included a piece of Muggington Field, comprising strips of land between Stanbridge and Leighton Buzzard. Without the money to develop and expand his farm, Joseph and Phoebe were forced into ever more desperate circumstances until finally, on the 9th of July 1788, the last piece of land owned by the Tearle family in Stanbridge was sold. Joseph and Phoebe died paupers. A strip of Muggington Field that was bought from Joseph and Phoebe was purchased at the time by the family of Lawrence Cooper, the churchwarden who opened the church on the morning of TearleMeet Two in 2008. 220 years after that sale, Lawrence still owned the land.

This Thomas Tearle, the father of Joseph, was born in Stanbridge in 1709 and married Mary Sibley from Houghton Regis on 27 May 1730. They had eight children, of whom seven survived. Thomas died in Leighton Buzzard in 1755 and Mary probably lived with Joseph and Phoebe until her death in 1792. Joseph died in 1790 and Phoebe, who was undoubtedly the leading force for Methodism in the Tearles, died in 1817.

An examination of the list of John’s ancestors on page 2 will reveal that all the people on that list have had their stories told, beginning with John Tearle 1916 and Jean nee Searle, and ending with Thomas 1709 and Mary nee Sibley. It is time now to look in a little more detail at the stories of those in John’s family who accepted a role in the military.

Military lives

From the brief view above of the story of Enoch’s military life; it would seem that much of it was spent in Ireland, although 9yrs were spent on service abroad. It has already been recounted that he joined the 2nd Battalion 4th Division, The King’s Own Royal Lancashire Regiment, and he was discharged after 21 years, still with the rank of private. His boys were to change all that; no mere private rank for them. From a glance at their birth dates, it can be seen that two, at least, were prime candidates for joining the armed forces in the First World War:

Jeffrey Jones Tearle 1871

John Herbert Tearle 1881

Samuel Hugh Tearle 1889

John Herbert Tearle, John’s father, might have been 33 in 1914, but that did not stop the armed forces from recruiting men of that age, especially if they already had military experience. Between John Herbert and Samuel Hugh was Katherine Mary, born in 1885. A long search attempting to find her in one of the many women’s auxiliary forces, or in a women’s group, was carried out, but there appears to be no documentation. Her contribution has been lost amongst the myriad grains of sand in the great hourglass of events that was the First World War (WW1). Millions of women spent huge amounts of time and energy – and their lives – helping in the war effort and there is no doubt that Katherine Mary joined in that work. Now, however, it is time to start at the top of the list of Enoch and Elizabeth’s children – with Jeffrey.

Jeffrey Jones Tearle was born in the Aldershot Camp hospital in 1871, and baptised later the same year. The camp had a hospital, and given that Jeffrey consistently gave his birth address as Aldershot, It is a reasonable assumption that he was born on site, in a vast camp that usually held in excess of 10,000 people. It is difficult to tell if there were married quarters, but Enoch was fully engaged in his army duties, and his family were born wherever he was at the time. The camp had a Methodist chapel, and a Primitive Methodist chapel, so it is very likely that Jeffrey was baptised in one of them, and it is equally likely he went to a school in the camp.

On 28 October, 1886, Jeffrey joined the army, and not just any regiment, either; the Royal Lancashire Regiment – in other words, the King’s Own. Since he is following his father in this, and he signed up in the Buttervant Barracks, North Cork, it is also likely that he took his father’s advice on the next decision; he signed up for 12 years. He was 15 years and 3 months old, and he was already an office boy, perhaps employed by one of the companies in Aldershot town, or perhaps somewhere in Ireland. He was 5ft 4in tall and weighed 100lb. He had hazel eyes, auburn hair, a mole on his left thigh and he was given the military serial number 1824. However, page three of his record, entitled his statement of services, is unhappily short. His service started on 29 Oct 1886 and ended on 28 July 1890:

Discharged, private, having been found medically unfit for further service.

His service had lasted 3 years and 243 days. On page four, there is a detailed breakdown of Jeffery’s service – he had been a drummer in the 2nd Battalion, Royal Lancashire Regiment. His next of kin was Enoch Tearle, residence 21 Victoria Park, Dover. For 216 days (9 September 1887 to 12 April 1888) Jeffrey was in India. This is the first documented sight of Enoch’s family (other than Enoch himself) being out of the country, anywhere other than in Ireland. The Actions, Movements and Quarters archive of the King’s Own Royal Regiment Museum in Lancaster showed where the 2nd Battalion was at any time, and where it went next:

| January 1886 | Quetta |

| March 1888 | Karachi and Hyderabad |

But there is more; on the sixth page of Jeffrey’s record there are two appearances before a medical board:

Quetta 18.2.88 Valvular disease. Recommended change to England. There is a stamp – Station Hospital Quetta

Curragh 9 June ’90 Valve disease of heart. For Discharge.

Also, it is clear the army approved of Jeffrey: habits regular, conduct good.

On the back of this form, there is a breakdown of where Jeffrey was, and what brought him to the medic’s attention. More importantly, it documents exactly where he was and when he was there.

Buttevant (Barracks, North Cork) 4.11.86 Ulcer 18 days in hospital

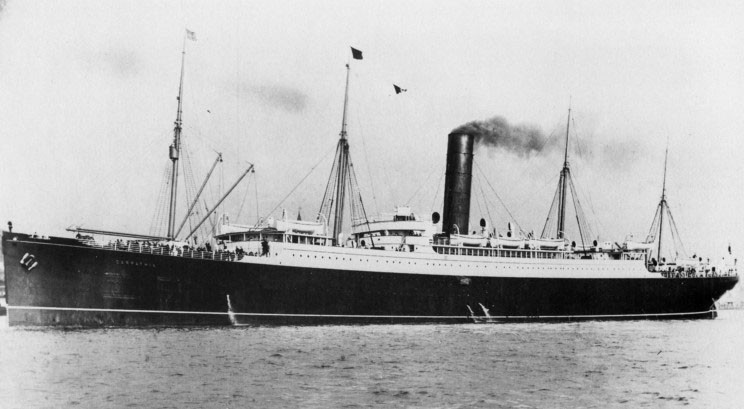

HMS Crocodile 9.9.87 No reason given

Bombay 6.10.87 No reason given

Narela (Delhi, India) 12.10.87 No reason given

Quetta (India) 15.11.87 Rheumatism sub-acute 17 days in hospital

Quetta (India) 12.2.88 Val. dis. of the heart 9 days in hospital

HMS Crocodile 17.3.88 No reason given

Netley (Hants) 12.4.88 Disability. Climate 25 days in hospital

Dublin 9.2.89 Itch 5 days in hospital

Dublin 7.9.89 S. C. Fever 13 days in hospital

Curragh 1.3.90 Anaemia 46 days in hospital

It transpires that the HMS Crocodile was a troopship designed to carry a full battalion of infantry, families and auxiliaries, a total of 1202. On 7 September 1887 she left Portsmouth with Jeffrey on board and on the 9th, Jeffrey was examined by the ship’s doctor. On 5 October 1887 HMS Crocodile arrived in Bombay and the 6th, Jeffrey was again examined by medical staff, this time in the Bombay military hospital. On 17 March 1888 HMS Crocodile left Bombay and on 12 April arrived in Portsmouth. Jeffrey was admitted to the Royal Victoria Military Hospital at Netley, near Southampton, where he stayed for 25 days. A man can get amazingly sick in India.

The beauty of this page is that it tells us that a 5ft 4in 18-yr old of only 100lbs is not really British Army fighting material, even if he is only a drummer. Secondly, it spells out in very clear terms where Jeffrey was and when. Thirdly it tells us that Jeffrey was there when the British Raj was at its height – Queen Victoria was proclaimed Empress of India in 1877.

The last sheet (dated 2.6.90) in Jeffrey’s army record details the process of leaving the King’s Own. He is now in the 1st Battalion (he started in the 2nd) and the first question on the form is:

What is the disability unfitting him for service? Valve disease of the heart.

Its origin, date, progress? Probably constitutional. Started with an attack of rheumatism.

Is it caused by his service as a soldier? Has not been caused or aggravated by military service

Is the disability permanent? Permanent, but he will be able to contribute a little towards ensuring a livelihood.

On 7 August 1897, still only 26yrs old, in spite of all his adventures, Jeffrey married Sarah Quarterman in St Ann’s Church, Lambeth, London. He describes himself as a clerk, and his father, Enoch Tearle, as a butler. His sister, Emily Tearle 1876 (the one born in Ireland) was a witness. The 1901 census reveals that Sarah was born in 1867 in Milton under Wychwood, a Cotswold village not far from Chipping Norton. The Gothic parish church of St Simon and St Jude dominates the countryside, which used to be mined for the yellow Milton Stone that was used for many local buildings. They are living at 47 Mayall Rd, Lambeth. It is close to the Brixton Tube station while the Railton Methodist Church is about 100 yards along and one street over. Jeffrey calls himself an O. C. shipping clerk. And they have a son, Reginald Herbert Henry Tearle, just 1yr old. The world has ticked over into the 20th Century, but the Victorians cling on; in this stretch of the road, there are many occupations: a general carman, a keeler groom, a dress wash, road labourer, railway guard, two greengrocers, railway labourer, laundry maid, bath attendant, milliner, shop attendant, and a traveling salesman. Most people here are Londoners, but only four houses are occupied by Brixton-born families. Jeffrey from Aldershot and the traveling salesman from Fyfield, Hants, are the only strangers from out of London. Little Reggie died in1904.

In 1911, Jeffrey and Sarah are living in 11 Kepler Rd, Clapham where he is a mercantile clerk for a provision merchant. Provisioning usually applies to the armed forces, in this case, probably the navy. They now have a second son, Edward Jeffrey Tearle aged 4, born in Lambeth. There is also a niece, Beatrice Soden, from Idbury in Oxfordshire. who is their housemaid along with a boarder, perhaps to augment the family income. Beatrice was born in 1882 in Chipping Norton to William Soden and Matilda nee Quarterman. They married in Chipping Norton in 1877. Matilda Quarterman 1856, of Chipping Norton, was Sarah’s sister. Their parents were Israel Quarterman 1822 of Denchworth, Berkshire (an ag lab all his life – the price you pay for living in the country) and Eliza nee Templer (probably Templar) 1822 of Curbridge, Oxfordshire.

The last document of Jeffrey’s life was the entry in the probate calendar of 1913. Jeffrey was living in 25 Kepler Road, Clapham. He died on 4 August 1913 at Guy’s Hospital, Surrey and had asked Benjamin Hewitt, a Prudential agent, to administer his estate of £249 14s 7d. Sarah died just over a year later, on 14 December 1914, asking Harriett Brewitt (the wife of Benjamin Brewitt) to administer her estate of £205 17s 4d.

There are two marriage records for an Edward J Tearle: one to Margaret Shelley in Essex 1935, and another to Leonora F Wedlake in Somerset in 1941. Until there is documentation to indicate exactly which Edward J is the son of Jeffrey and Sarah nee Quarterman, his story is suspended here.

John Herbert Tearle 1881

John Herbert Tearle, was born 1881 in Bisham, Berkshire, just too late for the census, but where, as noted earlier, his father was a butler. In 1891 he was 10yrs old, and a scholar, living with his mother, who was a dressmaker. Spittal Street in Gt Marlow had a Wesleyan chapel in 1891, and there was a Borlase school not far away, a free school for twenty-four boys. It is very likely that John H would have gone to the former, but he definitely went to the latter. The Slough, Eton and Windsor Observer of 8 January 1916 notes:

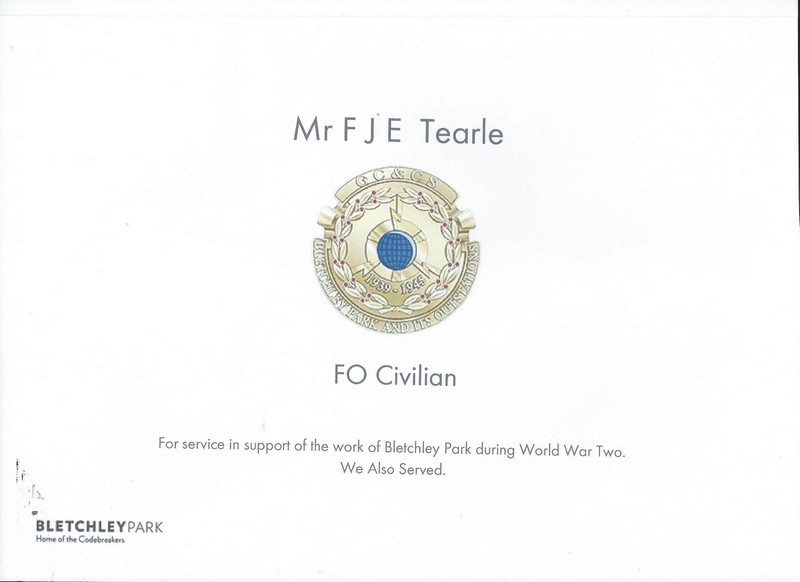

“The list of successful candidates in the qualifying examination for naval cadetships, to enter the Royal Naval College, Osborne, in January includes… Francis John Enoch Tearle (Borlase School) son of Mr J H Tearle, an old boy of Borlase, and grandson of Mr E Tearle, of New Town.”

In the not too distant future he would be an engineer and an accountant, so his education had to have been better than a plait school in Bedfordshire. There is no mention of the Wesleyan chapel being used as a school, but I am certain that you cannot rule it out.

After his very brief flirtation with army life, and some study and some experience in the intervening years, John Herbert married Mary Ward in 1900, in the Westminster district of St George Hanover Sq. in Central London. There are no further details. It is also difficult to find out very much about Mary, too, but it is likely she is the Mary 1881 who is in the 1881 Battersea, Surrey, census with her father William Ward 1835 born in Westminster, her mother Catherine, born in Buckinghamshire and three other children. Her father is a general merchant, described by the enumerator as living in a house at 12 Arthur St: “shop, dealership, rope, bottles, bones and old clothes.”

In 1901, John H and Mary Tearle are living in 107 Brook St, in the parish of St George the Martyr, Southwark. This is a darkly handsome church full of menace and foreboding, on a corner of Borough High Street. It is worth the train fare to London Bridge and a walk through Borough Market just to visit it. Mary is not given an occupation, but John H grandly calls himself accountant, and then reminds the enumerator (in brackets) that really he is only a clerk – oh, and an engineer. The enumerator dismissively encodes him as CC – commercial clerk.

Brook St, Southwark (nowadays called Brook Drive) is a very interesting, and a very mixed, street. There are new families from Germany and Ireland, and out-of-towners from Essex, Buckinghamshire, Wheathampstead, Portsmouth and Boughton. There is also a selection of Londoners from all around the city – such as Westminster, Southwark, Lambeth and Newington. The collection of accents you would have heard as you walked in old Brook Street, may have come as quite a surprise, but it does show London growing and diversifying. The occupations are mixed, too, comprised mostly of working class people wanting to move up the aspiration ladder to a better, more stable life. There is a police constable, three teachers, a stone mason, a commercial clerk, a coppersmith’s apprentice, a tailoress, a police sergeant, a home health worker, a bookbinder, a journalist, a housekeeper and a carriage maker. Only one couple is older than 41yrs in the entire street, and that is the 63-yr old bookbinder and his housekeeper wife.

As early as 1897, John H was working for the Metropolitan-Vickers Company (M-V). There is a history of the Metropolitan-Vickers Electrical Company Ltd, written by John Dummelow in 1949, and in a chapter entitled BRITISH WESTINGHOUSE from 1899, the first decade: the author describes the events of the first ten years. In 1907, John H is credited with a job of some authority, as both an accountant and an engineer. In 1917, he was assistant secretary and treasurer, and in 1920 (he was called the comptroller) he resigned, after twenty-three years with Westinghouse companies. Westinghouse is an American company, still well known, which made a large range of mostly industrial electrical items – motors for trams and generators for hydro-electric power stations, for instance. The Metropolitan-Vickers Company made products under licence from Westinghouse, firstly (ie before 1910) in Old Broad St, London City.

In the 1911 census, the last comprehensive view of John H and his family, he is in Lancaster. His address is Clifton Bank, Church Rd, Urmston. These days, it is just another suburb of Manchester, but possibly, in 1911, it did seem a bit further away than an easy commute, perhaps even a little bit countrified. However, the main reason for living there was to be reasonably close to Trafford Industrial Park, where the M-V company had built a substantial manufacturing plant. John is 30 and Mary is 31, she has been married 10yrs and has had three children, of whom three are still alive. John is an accountant for an electrical manufacturer. They are living in a nine-roomed house – and they have a 13yr-old maid, Ada Mason.

In 1916, John Tearle was born in Barton upon Irwell, Lancashire, presumably while they were still living in Urmston, but certainly still close to Trafford Park. He is the man at the centre this narrative. For John H, though, the overall picture, with nine years of his career with Metropolitan-Vickers to go, is one of comparative wealth and some seniority. In 1917, he was listed amongst the senior officials of the company.

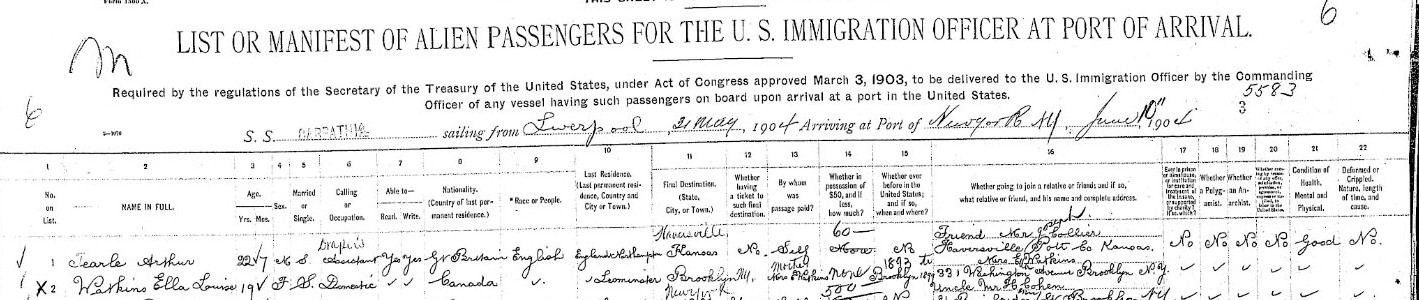

After 1920 there are only tantalising glimpses of John H’s life. Now that he is free from the constraints of the office, he takes up a challenge in South America, mostly Argentina, for which company there are no clues, but the voyage, and the ensuing adventure, do have consequences. The following is an entry in a ship’s passenger manifest:

Name: John Herbert Tearle

Gender: Male

Age: 42

Birth Date: abt 1881

Departure Date: 20 Dec 1923

Port of Departure: Southampton, England

Destination Port: Rio De Janeiro, Brazil

Ship Name: Zeelandia

Shipping Line: Royal Holland Lloyd

Master: A Dyker

This is three years after he left Metropolitan-Vickers, and there is a return journey:

Name: John Herbert Tearle

Birth Date: abt 1881

Age: 43

Port of Departure: New York, New York, United States

Arrival Date: 2 Jul 1924

Port of Arrival: Southampton, England

Ship Name: Almanzora

Although this transcript says the ship was returning from New York, the manifest itself says he was returning from Rio de Janeiro. John Herbert Tearle, 1881, engineer, is not to be confused with J Tearle 1892, engineer, who also traveled, this time on many noted journeys, to and from Buenos Aires and Liverpool. He was John Lawrence Tearle, the father of John L Tearle, scientist and author. The last, short, view we have of John Herbert is a mention in the National Probate Calendar of 1966. Address, 40 Villiers Ave, Surbiton. Died 25 October 1966, probate to Francis John Enoch Tearle, retired company director. £19023. We will see Francis later – we already know he is Uncle Frank – but there is so much more. The sum John Herbert left as his estate is handsome indeed.

Samuel Hugh Tearle 1889

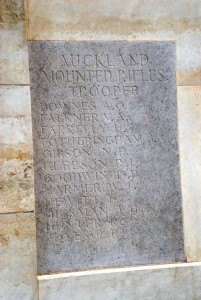

The last child born to Enoch and Elizabeth Tearle was Samuel Hugh Tearle, born in Marlow, Buckinghamshire, in 1889. When recounting the results of her researches into this family, Mavis Endall of Melbourne, the grand-daughter of Minnie Tearle 1874 (the one born in Woolwich) called him Uncle Sam. The Australians will be part of this story later. Samuel has already appeared in the 1891 census as a baby and in the 1901 census as a schoolboy, where the enumerator’s handwriting made them look like the Harle family. In the 1911 census he is in the army, he is a 21-year old lance corporal from Marlow, Buckinghamshire, and he notes that his father was born in Stanbridge, Bedfordshire. He is on the island of Jersey. Samuel is in a list of soldiers on page 193 of the census, but flipping back one page reveals that he is in the Parish of St Peter’s, and for the name of the head of the family, there is: Officer Commanding 2nd The King’s Own, St Peter’s Barracks, Jersey. Samuel has joined the King’s Own Royal Lancashire Regiment, and he is in the 2nd Battalion, just like Jeffrey. His elder brother, Jeffrey joined the King’s Own in 1886 and here is Samuel, in 1911, already a lance corporal and beginning his career in an outpost. It is not particularly difficult to trace Samuel’s life and adventures in the army, particularly during the Great War.

Here, in an encapsulated form, is where the 2nd Battalion went and what they did there:

| August 1914 | Lebong, India |

| November 1914 | Mobilised to be part of 83rd Infantry Brigade, 28th Division, at Winchester. |

| 16 January 1915 | Landed at Le Havre, France. |

| 17 February 1915 | Bayonet Charge at Zwartelen |

| 21 February 1915 | Repulse of Attack near Ypres |

| 3 May 1915 | Repulse of attack near Zonnebeke |

| 8 – 13 May 1915 | 2nd Battle of Ypres: Battle of Frezenberg |

| 8 May 1915 | Repulse of attack at Frezenberg |

| 25 Sept – 8 Oct 1915 | The Battle of Loos |

| November 1915 | Embarked for Egypt |

| January 1916 | Landed in Macedonia (Salonika) |

| 13 October 1916 | Capture of Barakli Dzuma |

| March 1917 | Battle of Doiran 1917 |

| 23 June 1917 | Raid at Brest |

| 25 February 1918 | Raid on Bursuk |

| 18 September 1918 | Battle of Doiran 1918 and advance into Bulgaria. |

| 10 November 1918 | Moved to Chanak |

| December 1918 | Turkey |

| 13 March 1919 | Reduced to Cadre |

| March 1919 | Returned to Tidworth |

| July 1919 | Disbanded and reformed |

Those who have little knowledge of WW1 will still have heard of some of these battles, because they were the sites of vast bloodshed. Two in particular stand out: Ypres and Loos.

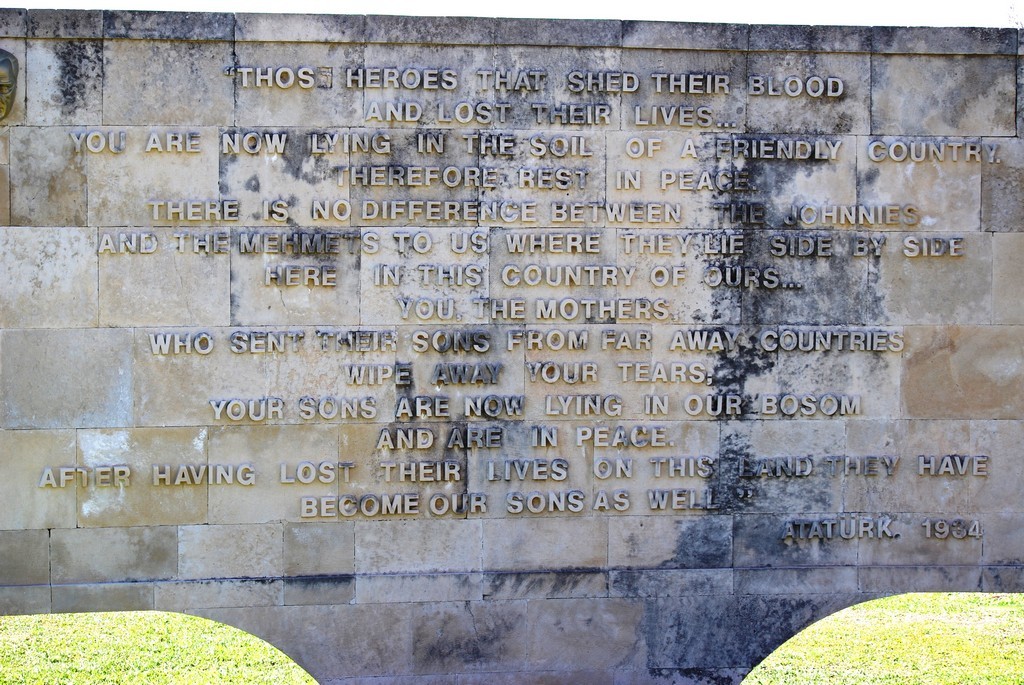

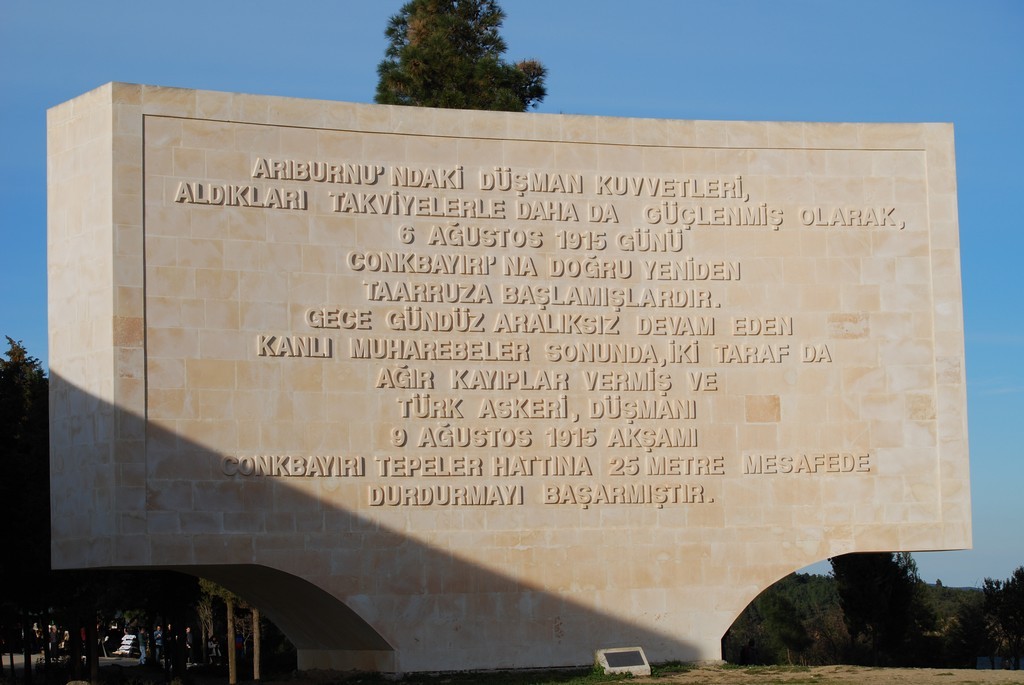

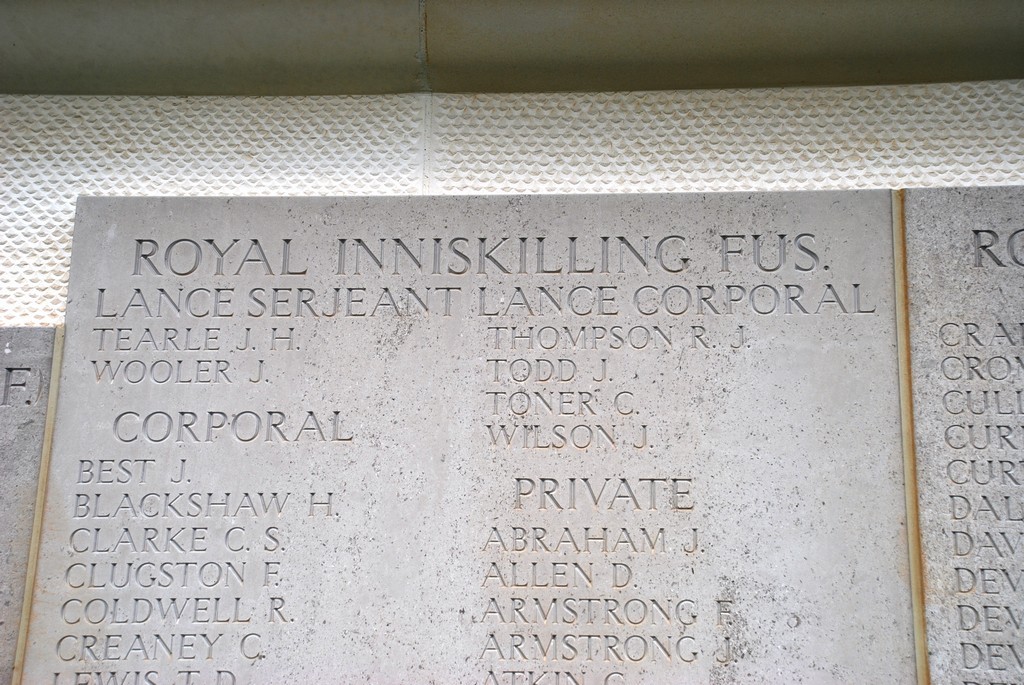

Ypres – you will have seen on television the recent excavations of battle trenches near this town in Belgium; English soldiers gave Ypres the name Wipers. Eeepr – can you imagine an Eastcheap cockney coping with that? The first battle of Wipers was a huge battle that lasted weeks, and then just died away. Hundreds of thousands of men (on both sides) were killed by machine guns and huge field guns that pounded the town and everything around it. Not a yard of ground was gained or lost. Then there was the second battle of Wipers. Same result. Then there was the third battle of Wipers, usually called Paschendale, being the name of a ridge that the armies fought over. There were half a million casualties. A huge memorial was built there, called the Menin Gate. It is the gateway into Ypres and has the names of 64,000 men whose bodies were never found. Those names filled the Gate, and the overflow of 8,373 men were written on tall tablets on the Tyne Cott memorial a few kilometres from Ypres

The battle of Loos is described in detail by the Western Front Association: www.westernfrontassociation.com but suffice it to say that 75,000 British soldiers were involved, and that it marked the first time that the British army used poison gas. Samuel was involved in all its horrors from trenches on and near the front line. That is where the 2nd Battalion always was.

From January 1916, when Samuel landed in Macedonia, until he finally left Turkey, the 2nd Battalion King’s Own Regiment fought the battles that lead to the end of the Ottoman Empire. Chanak on 10 November 1918 refers to the surrender of Constantinople, and Turkey with it. The following day, 11 November 1918, the Germans surrendered. These days we call it Armistice Day. Samuel H and others of the 2nd Battalion, as members of the British Army, marched into Constantinople, to keep the newly-declared peace and to start the process of delivering the war-torn world back to the politicians.

It was necessary to outline these events to show that Samuel was there when WW1 started, and he was still standing when it ended. There is, in the King’s Own Regiment Museum, a photo of Lt Samuel Tearle taken with a group in Salonika. Samuel’s medal card is most interesting to study because it is, in a highly condensed form, the story of his life in WW1. Firstly, there is a big red stamp 1914-15. There is his name TEARLE, Samuel Hugh, then the Corps: Royal Lancashire Regiment. Rank – sergeant, and his regimental number – 10220. This means that in 1914, when the war started, Samuel was already a sergeant. There is no date given, but in blue there is recorded Lt and a red pen note saying comm’d, meaning commissioned. He had been made a full lieutenant, not just an acting one. The medal record goes on to say the THEATRE OF WAR was France. The official landing date of the 28th Division was 16 January 1915. Samuel was awarded the 1914-15 Star, for being in the war from that date, as well as the Victory Medal and the British Star. Interesting, also, is his address:

38 Cedar Terrace, Lancaster Gate, W.2.

Lancaster Gate is a handsome, stone-faced, multi-storey, 19th Century development in London, part of which borders Hyde Park.

It would be informative to see the Service Record for Samuel Hugh but it has never surfaced, and as a result, there is no record of how and when he left the army, but a note in the London Gazette of 10 February 1919 announces he was temporarily made a captain whilst he operated as an adjutant. That is a very good rank indeed, even more so because he rose to it from starting as a mere private.

Now, let’s go back to India. You will see in the Actions and Movements list above that Samuel was in Lebong with the 2nd Battalion in August 1914, then in London for the November merge with the 28th Division, then in France on 15 January 1915. I think it was Rosemary Tearle of Auckland who found this:

Marriage in India:

Groom’s Name: Samuel Hugh Tearle

Bride’s Name: Dorothy Kate Parkhurst

Marriage Date: 04 Dec 1913

Marriage Place: Colaba, Bombay, India

Groom’s Father’s Name: Enoch Tearle

Bride’s Father’s Name: William Parly Parkhurst

Groom’s Marital Status: Single

Bride’s Marital Status: Single

Now we know why he had a London address. Amongst the British expat community, he had found a London girl – and married her. Their first child, a son, was born in Lebong in 1914. They called him Jeffrey Parkhurst Tearle. The records for Samuel and Dorothy are very scarce from this date on, and there is no indication of when, or under what conditions, Samuel left the army. In the London Electoral Roll of 1936 they are in Acton W11, number 39, 2nd Avenue. In 1939, they are in 39 Eastvale, Acton. Both addresses are Acton – North East Ward.

On 18 October, 1949, there is a passenger list for the R.M.S ORANTES of the Orient Line for Mr S H Tearle and Mrs Tearle, both 60yrs old, from 15 Vale Court, Aston Vale, London W3. They are sailing to Melbourne, where they intend to stay permanently. In the electoral roll of the State of Victoria, there is a hand-written addition to the Batman, Victoria, roll of Samuel Hugh Tearle. In the 1958 electoral roll of Footscray North, Gellibrand, Victoria, Samuel Hugh is living at 10 Macedon St, W10 where he is a clerk. There are other men, each with their wife, on this page, so I do not know where Dorothy Kate is.

The last sight we have of Mavis’ Uncle Sam is the information given to us on his death certificate of 11 May 1961. He was living at 28 Hawson Avenue, Glenhuntly, Victoria, he was 72 years old. He was married in India when he was 24 years old, to Dorothy Kate Parkhurst, and at the time of his death he was still married. He had a son, Jeffrey, who was deceased, and a daughter Geraldine, who was 42 years old. The certificate was signed by D. L. Endall of 7 Wyalong St, Sunshine, Victoria. I do not know exactly who D L Endall was, but we do know the Endalls; Samuel’s elder sister, Minnie, married Joseph Endall in Islington in 1894 and emigrated to Melbourne in 1924. We can now see that Samuel went to Melbourne to live near her. Dorothy Kate was still alive when Samuel died so I am still no wiser as to how the voting rolls have separated them while they were living at the same address, but we do know they were living together. Dorothy Kate died in Murchison, Victoria in 1984.

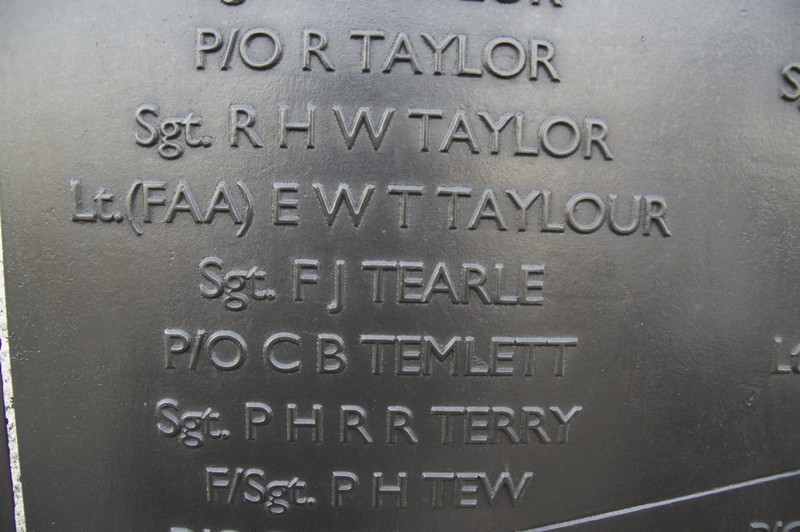

Since Jeffrey Parkhurst Tearle 1914 is Samuel’s son, I will look at his story before moving on to the last of Enoch’s family to have a military career.

Jeffrey Parkhurst Tearle

There is a scarcity of documentation for Jeffrey P that is frankly disappointing. There is a document called Army Returns, Births 1911-1915 which is only an index of the location of the birth records for the babies listed. However, it does indicate that Jeffrey Parkhurst Tearle was born in Lebong in 1914.

I do not have any military records for Jeffrey P, but his death as recorded by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) is revealing:

Name: TEARLE, JEFFREY PARKHURST

Initials: J P

Nationality: United Kingdom

Rank: Sergeant

Regiment/Service: King’s Own Royal Regiment (Lancaster)

Unit Text: 2nd Bn.

Date of Death: 21/11/1941

Service No: 3709500

Casualty Type: Commonwealth War Dead

Grave/Memorial Reference: 12. D. 23.

Cemetery: KNIGHTSBRIDGE WAR CEMETERY, ACROMA

He, too, had followed Enoch into the 2nd Battalion, the King’s Own. He was 27yrs old and he had risen to the rank of sergeant when he died. It is likely that Jeffrey P volunteered to join the army otherwise, of all the units he could have joined, it is very unlikely he would have been conscripted into the 2nd Battalion The King’s Own. The assumption, then, is that he joined up when he turned 18 years old, and that in turn means he had been in the army since 1932.

If we have a look at the Actions and Movements section of the King’s Own, we can clearly see that for the first six years of his army life, he was in Britain. In 1938 the entire regiment was shipped to Haifa. This would appear to be in preparation for the Peel Commission plan to partition Palestine.

1920: The King’s Own Royal Regiment, Lancaster

| March 1925 | Rawalpindi, India |

| December 1929 | Khartoum, Atbara and Gebeit |

| December 1930 | Whittington Barracks, Lichfield |

| November 1934 | Aldershot |

| September 1938 | Haifa, Palestine |

Then World War Two (WW2) broke out.

2nd Battalion King’s Own Royal Regiment, Lancaster

| August 1940 | Egypt |

| February 1941 | Syria |

| September/October 1941 | Tobruk |

| December 1941 | Egypt |

| February 1943 | Ceylon |

Here is the story, as told by the Kings Own Museum, of what happened in Tobruk and it covers the events of 21 November 1941, the day Sgt Jeffrey Parkhurst Tearle was killed. Briefly, the town of Tobruk was under siege by General Rommel’s forces.

A break-out from Tobruk was planned to coincide with an advance from Egypt by the Eighth Army. The attack was launched on 18th November after many days of planning, mine clearance and careful preparation.

The fighting was indecisive at first and was in full swing on 20th November when 2nd King’s Own was ordered to attempt to break out. Each section of the battalion was armed with a Bren gun and thirteen Bren magazines; each rifleman carried a hundred rounds in bandoliers and three grenades; in addition each platoon had two Thompson sub-machine guns and one anti-tank rifle.

On 21st November as tanks moved forward and broke the silence of the night, A and D Companies were in the front line when a tremendous artillery barrage opened up but most shells fell behind the battalion. As British guns opened fire and the tanks moved forward followed by the carriers so many tanks were disabled by mines that most were knocked out before the infantry were ordered to move. Despite this, D Company moved forward and took their position, ‘Butch’. A Company advanced with C Company in support and found themselves held up by a strong point called ‘Jill’.

Whilst D Company was able to hold their position, A and C Companies were forced to withdraw from ‘Jill’ during the afternoon and, with the help of B Company, formed a new defensive position on ‘The Crest’. As a result of this action the battalion took about 300 German prisoners and were able to hold ‘Butch’ until 24th November when they were relieved by 2nd Battalion Leicester Regiment.

Francis John Enoch Tearle 1902 (Uncle Frank)

In the 1911 census, Francis was eight years old, and he had been born in the Regent’s Park district of London to John Herbert Tearle 1881 and Mary nee Ward. He was the elder brother of John 1916. This census demonstrates a growing trend in modern society; large numbers of people do not live in villages or communities any more, they live where their employment takes them, and they make what they can of the community they find themselves in when they get there. If they work for a large company, the company will send them wherever it is necessary for their workforce to be. If they do not wish to move, then their employment is terminated. It was noted earlier that Metropolitan-Vickers had an office, and probably a workshop, in Old Broad St, London, and they also had premises on the corner of Ludgate Hill and Farringdon Rd, in the very heart of London City, but since then they had built a huge manufacturing plant in the Trafford Park industrial zone, Manchester. This is where Francis first appears, living with his family in Church Rd, Urmston. Now, Urmston is only six miles from Manchester city, but Metropolitan-Vickers was still allowed to build a coal-fired manufacturing plant close by. The low-lying nature of the site meant they also had to build a water tower. Instead of it being an eye-sore, it is championed as a wonderful iron structure, of magnificent proportions. Its photograph adorns the wall of their head office. A modern, industrialised Britain cannot now blame the emerging nations for their pollution – it showed the way to modernisation, and that includes pollution on a vast scale, low working-class wages, and mass-migration. John Herbert’s life is a micro-dot of what is to come: born in Bisham, Berkshire, he takes a wife from Surrey, has two children in London and then has Kathleen May in Flixton, Manchester. He is no longer a Berkshire boy, he is an indigenous Englishman, and instead of living with the mores and customs of his boyhood locale, he has to learn what it means to be English, and to live his life within a much more open moral and social compass. In his case, he has his Methodist upbringing to guide him. Whether or not he has brought up his family as Methodists needs to be documented, but he has definitely brought them up with the highest standards of citizenship and morality. Francis John Enoch Tearle 1902 is an example of just how high an ordinary family can aspire, beginning with the illiterate but deeply moral and intensely hard-working Abel Tearle and Martha nee Emmerton.

A highly condensed biography was forwarded from Teresa of Brisbane, but the source document remains unknown:

“Tearle, Francis John Enoch, CBE (1965), s of late John Herbert Tearle; b 1902: educ RN Colls Osborne and Dartmouth and Manchester Univ; m 1926, Nettie Liddell, dau of late Matthew A McLean; served 1919-20, midshipman RN and in 1939-45 War as Lt RNVR in Middle East; chartered mechanical engr; gen man Metropolitan Vickers Electric Export Co 1949-54; man dir Associated Electrical Industries (Overseas) Ltd; dir Assocn E.L. Industries Ltd; pres Eutectric Co Ltd; master Worshipful Company of Broderers 1974-75; Travellers’ club and RAC; Shetland Park, Horsley, East Horsley, Surrey”.

Royal Navy cadets studied at the Royal Naval College Osborne, on the Isle of Wight, for two years, then went on to RN College Dartmouth. Osborne closed in 1921, but Dartmouth is still going strong. It is housed in a gloriously flamboyant Victorian building overlooking the harbour. It still trains naval officers with the aim:

To deliver courageous leaders with the spirit to fight and win.

After his two years study in Dartmouth, Francis went to sea and served a year as a midshipman, meaning an officer cadet. Osborne charged £75 a year to attend and some 30 cadets were subsidised to about £40. It is unlikely Francis was one of the latter, given the position his father had attained in Metropolitan-Vickers by 1919. Francis then went home to Manchester where he attended the College of Technology. It is now called the School of Mechanical, Aerospace and Civil Engineering, and since 1994 has been part of Manchester University. He applied to join the Institution of Mechanical Engineers on 26 April 1923, giving his address as C/- Mrs Clarke, “Hazeldene” Moss Lane, Bramhall, Stockport. He was required to seek a proposer who “from personal knowledge recommends him as a proper person to become a Graduate or Student”. His proposer was Professor Dempster Smith, MBE. A note about him from Manchester University says that during WW1

He was awarded the MBE for his work on the heat treatment of paravane blades. A paravane is made up of a strong steel cable and of two razor-edged blades. The cable is towed alongside a vessel such that the attached blades cut free the moorings of submerged mines.

An undated photograph of the mine-sweeping paravanes in production at Metropolitan-Vickers is reproduced on the same page as the photo of John Herbert, so it is possible to see how Professor Smith made Francis’ personal acquaintance, and this in turn tells us that Francis liked to explore the workshop at Trafford.

In 1926 he married Nettie Liddell McLean, but there is no trace of this marriage in England or in Scotland. In 1911, Nettie was a seven-year-old in Stretford, near Manchester. The registration district was Barton upon Irwell, the same district that would register the birth of Simon’s father in 1916. Her father, Matthew Adam McLean 1868 was a Scot from Mossend, Lanarkshire, near Motherwell. His occupation was described as Supervisor at an electrical Manufacturer, in other words, Metropolitan-Vickers. He was working at their brand-new plant in Trafford, and living not very far away from the site. At this time, a Ford Model T assembly plant was also built in the same park. Nettie’s mother was Janet Goodlet 1873 from Coatbridge, Lanarkshire, about 10 miles east of Glasgow. She and Matthew married in Glasgow in 1895. There is no indication so far as to who inspired the Liddell surname in Nettie’s name.

In 1941, Francis is aboard the CANADA, from Liverpool to Port Said. It is early in WW2 and Rommel has been very successful in battling Allied forces all over North Africa. He became very sick and flew back to Germany to be treated, and to meet with Hitler. The Allies have also found an Enigma machine, and the work in Bletchley Park is uncovering its secrets; Rommel is beginning to lose major battles. Francis says he is living at 95 Moss Lane, Sale, Cheshire, so he has not moved far from Trafford, and describes himself as a civil servant. In 1942, he is listed in the royal naval volunteer reserve as (SS) Francis John Enoch Tearle 13 Jan. It is safe to say that his voyage to Egypt in 1941 was on His Majesty’s Service, probably navy business. It can be seen from the very truncated biography above that he was a lieutenant in the RNVR in the Middle East, so it is no surprise to see him in Egypt.

There is nothing more about Francis until at the end of 1948 he was appointed managing director of the Metropolitan-Vickers Electrical Export Company Ltd because he had long Russian experience. On page 239 of the M-V history book, there is a photo of Francis, along with a photo of the Johannesburg office, with which, no doubt, he was very familiar.

On 9 May 1952, Francis and Nettie are to be seen in a passenger list on the SS ARGENTINA STAR of the Blue Star Line, traveling back to London from Rio de Janeiro. They give their address as Goldrings Rd, Seven Oaks, Surrey. He is a director, Nettie is a housewife, and their country of last permanent residence was Turkey (OHMS). It looks as though Francis’ company has been asked to report on something in Turkey, it has taken more than a year, and now that the work is done, Francis and Nettie are going home.

A passenger list from the CHUSAN in 1960, shows Francis sailing from Hong Kong to Bombay. Which means he has business in India, too. That is not unexpected since he is working in an export business, but it is one more tie with India. This is reinforced with the last sight of Francis in the Tearle Tree archive; a bio written on him as a contributor to the Journal of the Royal Central Asian Society Volume 52 Issue 3-4 of 1965:

- J. F. E. TEARLE, C.B.E., is Managing Director of Associated Electrical Industries Overseas Ltd. In 1964 he led an F.B.I. Mission to Pakistan to study and report on its economic situation, since when A.I.E. have investigated and reported upon the feasibility of manufacturing heavy electrical equipment there. In 1955 Mr Tearle negotiated the Heavy Electrical Project Agreement with Government of India under which A.E.I. Ltd. were appointed Main Consultants.

Volume 52, 1965 contained an article written by Francis called “Industrial Development in Pakistan” in which he presented views about the relative merits of encouraging development of East Pakistan at 60% of national expenditure on industrial development and 40% for West Pakistan, mostly because of the “menacing growth of population in the East”. Since then the East has become Bangladesh.

John L Tearle wrote to Mavis in Dec 2002: