Vicarage Rd Cemetery

Elaine and I visited the Vicarage Rd Cemetery in Watford on 24 Apr 2011, armed with a printout of Tearle names and grave numbers given to Iris Adams and me by the warden of Watford North Cemetery when we went looking for Tearle graves there a couple of years previously. At Watford North, we had found Reginald Frank Tearle.

To start with, the Vicarage Rd Cemetery is pretty big. Without a map, it would be almost impossible to find any particular grave, and even with a map, the layout is somewhat chaotic, due mostly, I should think, to the number of times it has been enlarged, and re-numbered. One of the saddest things was that some of our earliest graves, and therefore the most important, had been re-used, and if there had ever been a headstone, it was now long gone. The only clue was in the catalogue number of the particular site.

There was a WW1 Great Cross close to the main entrance, and visible from Vicarage Rd as you drive past the Watford football stadium, to indicate that there were CWGC headstones in the cemetery, but there was no enclosure of a group; the headstones were wherever you could find them.

Vicarage Rd Cemetery War Memorial, Watford.

We paid our respects at the War Memorial, took our list of grave numbers and gradually found them all.

The triangle in the lower foreground is grave D-DED 441, for Charles Tearle b/d1879. The headstone on the left of the picture was also placed in 1879. Charles was the infant son of Jabez 1844 and Susannah nee Payne.

Grave D-DED441 the triangle Charles Tearle d1879 Vicarage Rd Cemetery.

We called this Tearle Corner; the highest concentration of Tearle graves close to each other we had ever seen. There are actually three graves, but they are occupied by eight people in total

Tearle Corner, Vicarage Rd Cemetery, Watford.

This is a general view of site 953-K: George 1902-1931, Edward Joseph T 1874-1933, and Jane 1871-1944. George 1902 was the son of Edward Joseph Tearle and Jane nee Picton.

Tearle Corner grave K953: George 1902-1931, Edward Joseph T 1874-1933 and Jane nee Picton – Vicarage Rd Cemetery, Watford.

The headstone for 953-K. Edward Joseph Tearle was the son of Jabez 1844 and Susannah nee Payne. Jabez was the son of George 1818 and Annie nee Haws. Thomas 1737 via Fanny 1780

Tearle Corner headstone K953 – George 1902-1931, Edward Joseph T 1874-1933 and Jane nee Picton. Vicarage Rd Cemetery, Watford.

William 1852 married Catherine Newsham Hodson in 1875. He was the son of John 1824 and Sarah nee Bishop of Slapton, and when John died young, William was brought up in Watford by his uncle George 1818 and his aunt Annie nee Haws.

Tearle Corner grave K862 William Tearle 1852-1913, Vicarage Rd Cemetery, Watford.

There is one name on each wing of site 861-K, the grave of Mabel Tearle 1884-1955, Elizabeth Strickland 1821-1903, Elizabeth Louise Tearle 1852-1924 and George 1854-1945.

Tearle Corner grave K862 William and K861 Mabel Tearle 1884-1955 Elizabeth Strickland 1821-1903 Elizabeth Louise Tearle 1852-1924 George 1854-1945. Vicarage Rd Cemetery, Watford.

Elizabeth Strickland was the mother of Elizabeth Louise, so she was George’s mother-in-law, and Mabel’s maternal grandmother.

Elizabeth Strickland 1821-1903.

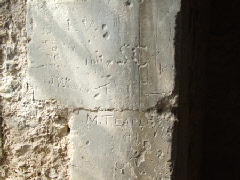

When you are given a printout of the grave numbers for a person, or number of people, there is also a rather vague map of the general locations (eg K) but the only way to tell where you are is to refer to the grave numbers, such as is shown here.

How to tell the exact grave number.

Mabel 1884-1955 is variously called Lizzie, Lizzie Mabel and Mabel, depending on the document in question.

Lizzie Mabel 1884-1955.

Elizabeth Louise (as here, or Louisa, sometimes) 1852-1954 was a London girl from Stepney, who married George 1854 in St Pancras in 1879.

Tearle Corner grave K861 Elizabeth Louise Tearle 1852-1924 Vicarage Rd Cemetery Watford

George 1854 was also a son of John 1824 and Sarah nee Bishop. He was firstly a grocers assistant in Dunstable but by the time he met and married Elizabeth Louisa Strickland, he was in London working as a railway clerk. Watford has strong railway links, so George has added family links in coming to Watford.

Tearle Corner grave K861 George Tearle 1854-1945

E-CON 76, the grave for Sarah Ann 1851, Elizabeth Amelia 1821, George 1818, Jabez 1844 and Lucy 1857; potentially the most important grave of all. It probably never had a headstone, and you can see that, sadly, the site is re-used.

E-CON76 – grave for Sarah Ann 1851 Elizabeth Amelia 1821 George 1818 Jabez 1844 Lucy 1857 reused.

E-DED 441 is the grave for Albert Edward Tearle 1906-1907. It is the unmarked grave in the centre foreground. Albert was the son of John Leinad T 1876 and Alice nee Allainey, and grandson of Jabez 1844 and Susannah nee Payne.

E-DED441 Albert Edward Tearle 1906-1907 unmarked grave Vicarage Rd Cemetery Watford.

F-974 Alice Mary Tearle 1868-1917 was the daughter of Thomas 1847 (the railway engine driver) and Mary nee Bowler. She is descended from John 1780 and Sarah nee Claridge. William 1749.

F974 Alice Mary Tearle 1868-1917. Vicarage Rd Cemetery, Watford.

F-892 The grave of Thomas Tearle 1847-1925 and Mary nee Bowler is immediately behind that of their daughter, Alice Mary 1868. Thomas is the son of Thomas 1820 and Sarah Jane nee Elliott. He is the grandson of William 1749.

F892 Thomas Tearle 1847-1925 and Mary nee Bowler. Vicarage Rd Cemetery, Watford.

615 H-CON (Below) Arthur Fred Elliott Tearle 1877-1948, Florence Mary 1905-1907 and Annie nee Hodges 1872-1954. Arthur is a son of Thomas 1847 and Mary nee Bowler, so he is the brother of Alice Mary, above.

615 H-CON Ewart studies the grave of Alfred, Florence Mary Tearle and Annie nee Hodges. Vicarage Rd Cemetery Watford.

Here is a general view of the graveyard showing the site of the grave of Arthur and family.

615H-CON Photo to show the location for the grave of Arthur F E Tearle 1877-1948 Florence Mary 1905-1907 and Annie nee Hodges 1872-1954. Vicarage Rd Cemetery, Watford.

561-L Mildred Annie Tearle 1884-1908. Unfortunately, this grave, too has been re-occupied and Mildred Annie’s name is no longer on it. Mildred was the daughter of Anne Elizabeth Tearle 1859 before Anne Elizabeth married Joseph Moore in 1888.

561-L – Foreground, reused grave of Mildred Annie Tearle 1884-1908 Vicarage Rd Cemetery, Watford.

The grave is definitely 561-L which is listed for Mildred Annie Tearle. Here is a close-up of the corner post showing (just) its number. She is the grand-daughter of Abel 1833 and Sarah nee Davis and g-granddaughter of Joseph 1797 and Maria nee Millings.

Marker post for grave 561-L

Below is a picture of plot 1150 L-CON for William 1857-1933. The clipboard marks the site. William married Mary Jewell nee Trust nee Cox. He was the son of Abel 1833 and Sarah nee Davis, so he was the brother of Ann Elizabeth 1859, and Mildred Annie’s uncle. Joseph 1737.

Grass plot 1150L-CON William 1857-1933. Vicarage Rd Cemetery, Watford.

Grass plot 1150L-CON William 1857-1933. Vicarage Rd Cemetery, Watford.

A general view showing the location of 1150 L-CON. The headstone beyond is for a chap called Rogers.

790-M As the corner post shows, the grave for Olive Archdeacon Tearle 1881-1985. This is not the name on the grave, so it’s another re-used site. She was the sister of Lizzie Mabel, featured above.

790M corner post for Olive Archdeacon Tearle 1881-1985. Vicarage Rd Cemetery, Watford.

Olive Archdeacon T is the daughter of George 1854 and Elizabeth nee Strickland. She was born in 413 Commercial Rd, Tower Hamlets, and George was in the railways as a clerk in those days.

Reused grave 790M for Olive Archdeacon Tearle 1881-1985. Vicarage Rd Cemetery, Watford.

The families:

There are three separate families associated with the headstones above:

Family 1.

Abel 1797 and Hannah nee Frost. He was the son of Fanny 1780 and g-son of Thomas 1737 and Mary nee Sibley. Two of his boys were the fathers of families as follows –

John 1824 and Sarah nee Bishop of Slapton – William 1852 and Catherine nee Hodson, George 1854 and Elizabeth nee Strickland.

George 1818 and Annie nee Haws’ son, Jabez 1844 and Susannah nee Payne and three of their sons, Alfred George 1872, Edward Joseph 1874 and John Leinad 1876.

Their sister Elizabeth Amelia 1821.

Family 2.

William 1749 and Mary nee Prentice

John 1780 and Sarah nee Claridge, whose children were all born in Leighton Buzzard. John was a member of the 2nd Dragoon Guards and father to a line of theatrical Tearles one of whom was Sir Godfrey Tearle, the movie and Shakespearean actor. He was also the father of many sons who joined the Royal Marines – at least four that I know of. Thomas 1847, the railway engine driver, married Mary Bowler. Their daughter is Alice Mary 1868 and their son is Arthur Fred Elliott T 1877. He married Annie Hodges and their daughter Florence Mary 1905 is featured on their headstone.

Family 3.

Joseph 1737 and Phoebe nee Capp. Their grandson Joseph 1769 and their gg-gson William 1857.

Joseph 1797 and Maria nee Millings. Joseph was the son of William 1769 and Sarah nee Clark, and grandson of Joseph 1737. Mildred Annie 1884 is their grand-daughter, the daughter of Ann Elizabeth 1859 and grand-daughter of Abel 1833 (and Sarah nee Davis) who was a son of Joseph 1797 and Maria nee Millings.

William 1857 was the brother of Ann Elizabeth 1859 and Mildred Annie’s uncle. He married Mary Jewell nee Trust nee Cox.